“Delta Drive” by Doug Webb

The first blues lyrics to ever truly resonate with me was a line from Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee that said simply: “I’d rather drink muddy water, sleep out in a hollow log.” The imagery spoke of pain beyond my teenage comprehension. It was colorfully rural and overpowering.

When mixed with tales of a midnight rendezvous at the crossroads with the devil, waiting for a train where the southern cross’ the dog, or a stint of hard time at Parchman Farm, it’s easy to see why the Mississippi Delta holds such mystique for musicians and blues aficionados around the world.

The flat somewhat oval shaped Mississippi Delta encompasses about 7,000 square miles, and with Memphis at the northern tip, and Vicksburg at the south, it’s banded together by the Mississippi and Yazoo Rivers.

At any given moment in the delta, images of chain gangs, cotton gins, riverboats and civil war battlegrounds seem to peer through an ethereal mist, and the blues permeates everything with an underlying sense of voodoo and superstition.

61/61

More than a decade ago, I began to hear about people going to the delta to pay homage to their musical heritage and my Nashville musician buddy, Jamey and I discussed the possibility of such a trip many times over the years. However, it wasn’t until I retired from my corporate Communications job that making such a pilgrimage became a real possibility.

The numerology was just too significant to delay any further: This would be my birthday/retirement trip; I would turn 61 years of age on Highway 61.

I spoke with people who had made this pilgrimage. We googled and collected all the information possible and closely followed the “Blues Traveling” guidebook. For this trip we would venture from Nashville to the Mississippi Delta via the Natchez Trace Parkway. Then head north through Mississippi and see the sites and visit the museums, gravesites and juke joints. We would arrive in Memphis on highway 61 on my birthday, meet our wives and celebrate with a couple of nights on Beale Street.

It was a pilgrimage to pay homage to many of the great blues musicians who had been such an important part of our lives. To traverse the same highways, to see where and how they lived, to stand at the final resting place of such greats as Robert Johnson, Charlie Patton and Sonny Boy Williamson II, put it all in a new perspective. After 20 years of my own corporate imprisonment I was wanting to ride that blues highway north to my own sense of freedom and rediscovery.

Greenwood with Hellhounds on our trail

I got to keep movin’

blues fallin’ down like hail

and the days keeps on worrying me

there’s a hellhound on my trail

After a months-long drought, the rain began even before we had packed the car and the windshield wipers rarely ceased to slap over the next few days. Heading south out of Nashville on the Natchez Trace Parkway, we spent the first day getting into position.

We took time to stop in Tupelo, the birthplace of Elvis to spend some time at the shotgun-shack museum dedicated to his memory. We also visited the Elvis’ teenage drive-inn hangout a few blocks away. At Johnny’s Drive Inn, we tried the traditional and famous dough cheese burger. In order to get more patties from a pound of meat, the cook started adding dough and it became a staple of the establishment. Dough burgers were a $1.39 and the full meat burger was $1.69. My advice is to spring for the extra 30 cents, but it was a taste of Tupelo and an insight into Elvis’ dietary desires. Please pass the peanut butter and bananas.

Delta Blues Begin

We cut over on highway 82 toward Greenwood in the late afternoon and pulled into town about sundown.

The next morning, we started early and headed for the Greenwood Blues Heritage Museum. Located in the old three deuces building—at 222 Howard Street—that once housed radio station WGRM on its second floor. This was the first station to broadcast B.B King live over its airwaves.

Enroute to the museum, we spotted two scraggly looking stray dogs of unidentifiable origin—one large and dark haired, the other smaller and sandy colored—sitting motionless on the street corner. A comment was made that this was our first sighting of hell hounds and we both chuckled. The weird thing is that over the next several days, we spotted similar pairs of dogs—same color and size—at least a half a dozen times, at various places along these dusty Mississippi county roads. It started to get strange.

This Greenwood Blues Heritage Museum now is an outgrowth of Steve Lavere’s private collection valued at more than a million dollars. The museum houses the largest collection of Robert Johnson materials ever assembled and includes many of Johnson’s original 78 recordings as well as a copy of this death certificate.

LaVere says the goal of the Museum is to raise the awareness of the part Robert Johnson has played in the history of Blues music and the role Blues music has played in the history of American music in general.

Johnson’s contribution to blues and rock and roll cannot be overstated and anyone who’s ever banged out a double-stop guitar lick owes a debt of thanks to Johnson. He was born in 1911 and became the most influential and probably best well-known Blues musician ever. His 29 original compositions became the link between the acoustic rural blues of the Delta and the electrified urban blues of the post-World War II Chicago as well as a direct link to rock & roll.

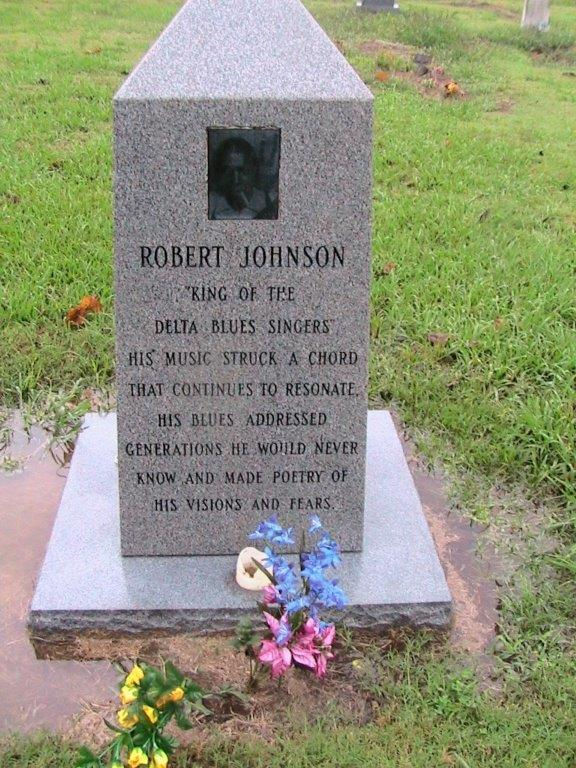

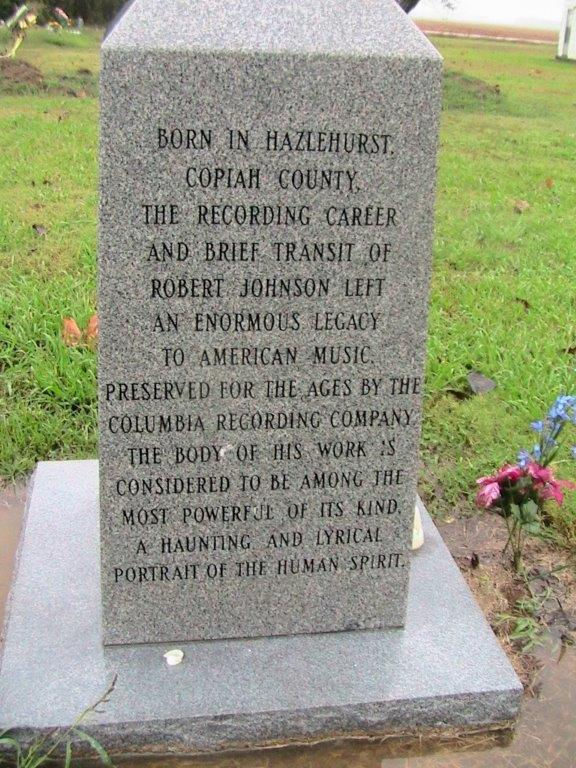

It was time well spent and having seen so much Johnson related memorabilia made sense since our first field excursion was to search for his grave site. This task made more difficult due to the fact that three separate graves claim to be Johnson’s final resting place.

The first site was just outside of Greenwood, and we crossed the Tallahatchie River on Money Road, and were soon heading down a fairly deserted stretch of two-lane blacktop. As we rounded a curve just a few miles outside of Greenwood, the Little Zion ME Church came into view.

Rain continued and through the blur of the windshield wipers we again saw two mangy dogs – one dark, one light – that stood motionless, their faces stoic as we slowly passed.

“Is that the same two dogs?” Jamey wondered. It seemed unlikely since that last pair of hounds had been seen several miles and several hours earlier.

At the back of the Little Zeon ME Cemetery, near a large tree was a monument placed by Lavere in 2002. Of Johnson’s three gravesites, this is believed to be his most likely one. Rosie Eskridge, who was 22 at the time of Johnson’s death, remembers her husband Tom digging the grave. Although she doesn’t remember the exact location, she says the casket rested under the large tree while the grave was being dug. Over time, the many unkept graves had become sunken and looking across the graveyard through the misty rain, the site looked timeless and eerie. I stood for several minutes in reverence and before leaving I reached into the pocket of my jeans and found a steel guitar thumb pick which I left on Johnson’s headstone.

Finding the other two locations, one in Quinto the other in Morgan City was easy thanks to the guidebook. I left metal guitar picks at all three sites. Briefly, I considered scooping up some mud from Johnson’s graves, in order to somehow become closer to the man and his music; however, something told me that this might be meddling with juju that’s better left alone.

Both sites were worthwhile, but with the Yazoo River flowing nearby the Morgan City location, it gave us cause to pause and reflect. Through the mist you could almost see and hear the ghost of some long-lost bluesman eternally walking these backroads.

We spent a good portion of the morning searching for the site of the three-forks juke joint; the site of Johnson’s last gig. Like his burial sites, there is some dispute over where the juke joint was located. However, after going back over our research material the most likely spot appears to be at the junction of highways 82 and 49 east. Today a church sits on that location but behind the building is a stretch of the old 49 east highway. With grass growing up between the cracks it too offers a little glimpse into the past.

Rick Kennedy, a PR colleague and blues/music historian who wrote the book, “Little Labels Big Sound” provided some much-needed background on the three-forks juke joint. Several years earlier, Kennedy learned that the three-forks juke was going to be razed and he made a pilgrimage to the site and salvaged some wooded window frames from the structure right after it was demolished.

It took months of pleading on my part for Kennedy to mail me a 6” piece of window frame with faded and pealing red and white paint. It is beautiful and I wrapped a leather strap around it and it hangs in my studio; one of my most prized possessions.

However, no piece of Johnson memorabilia comes without being shrouded in mystique. Kennedy told me he had given another piece of three-forks window frame to a friend who played guitar. This person slept with the wooden piece under his pillow for several weeks and it had an eerily profound effect on his playing.

Of course, I had to follow suit. For several weeks I slept with this chunk of wood tucked beneath my pillow. The results: No change in playing ability; new pain in neck from sleeping on a chuck of wood.

Birth of the Blues – Where the Southern Cross’ the Dog

If asked to cite a place were the ‘blues” began, you’d be hard pressed to find more fitting locations than Moorehead or Tutwiler.

In Green River Blues, Charley Patton sings about where the Southern Cross’ the Dog, and in his 1935 recording of The Southern blues, Big Bill Broonzy goes further to explain by saying, “…the Southern cross the Dog at Moorehead, mamma.”

Blues and trains are practically a synonym, and in this instance, it refers the north and south intersection of the still active Southern line and the Yazoo and Mississippi Valley line which was known as the Yazoo Delta. Some believe that Yellow Dog is a substitute for Yazoo Delta, while others say it refers to an old yellow dog who stood beside the tracks. Still, I’ve heard it refers to the circuitous route the train follows as in, “crooked as a dog’s hind leg.”

Greenville – Day 2

I went to the crossroads,

fell down on my knees

I went to the crossroads

fell down on my knees,

Asked the Lord above “Have mercy, now

save poor Bob, if you please.

Because of its mention in “Riverside Blues” the town of Rosedale has special meaning. In our research, we came across a story that hypothesized the intersection of highways 8 and 1 as the actual Crossroads. The theory was built on the premise that Robert Johnson was en route back to Rosedale on the night in question when he allegedly sold his soul to the devil. He had been playing in Yazoo City and Beulah and was heading back to Helena on the night in question.

No matter where you place the crossroads, the myth is built around an autumn night with a full, honey-colored moon shining down on a lonesome stretch of Mississippi back road near the river when the devil took Robert Johnson’s guitar, tuned it up and offered it back to Johnson. To accept the guitar meant he would acquire great musical skills.

Some images are best in black and white. So, it was a little disconcerting to come upon this intersection just outside of Rosedale on a rainy autumn afternoon to find it located near a big Piggy Wiggly food mart. Of course, we joked about a tired Robert Johnson being able to hit the Piggy Wiggly for some snacks before his important late-night meeting.

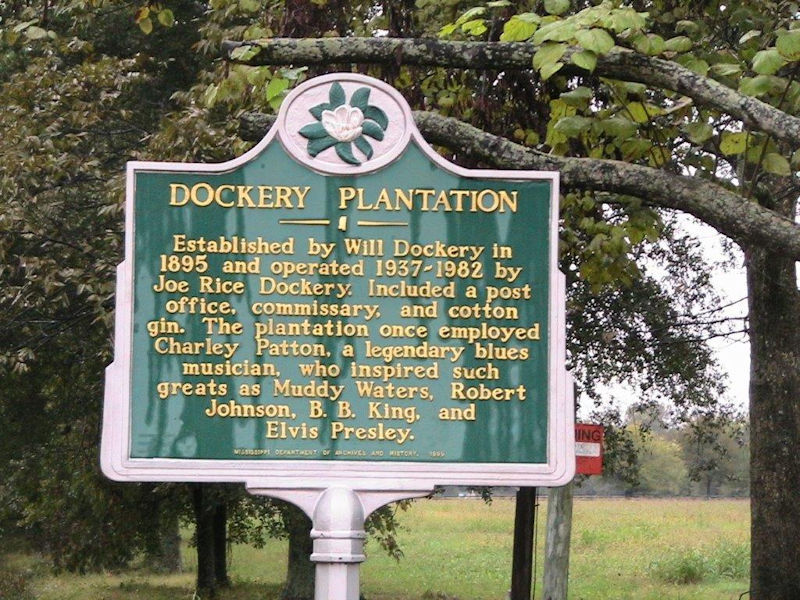

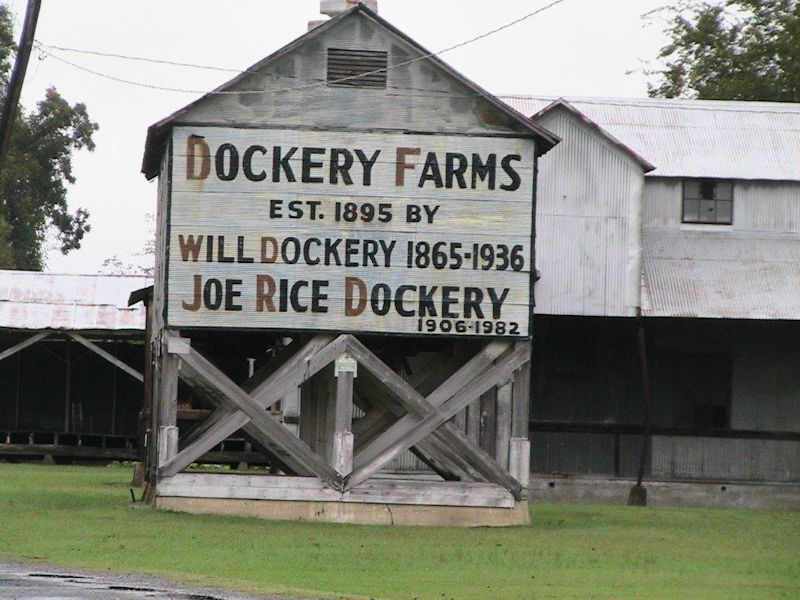

Heading to Clarksdale

Dockery Plantation, was once the home of Charlie Patton, Howlin’ Wolf and Willie Brown. Patton learned guitar from another Dockery resident Henry Sloan and Patton lived at the site off and on for 30 years. At one time, about 400 families lived on the plantation, and the Pea Vine Railroad stopped at the site.

Pulling into the driveway and seeing the familiar water tower was like seeing a photo from a history book come alive. It was worth pulling into the driveway to commemorate the moment.

We knew going in that Parchman Farm was going to be a quick drive by, but we had no idea how fast until we saw signs declaring “emergency stops only.” The vibe along the highway was as dark as the weather.

It was easy to envision shackled inmates chained together in long rows along the roadside. While this wasn’t the case, we were glad to put Parchman Farm in the rearview mirror.

Charley Patton mentioned the prison in Spoonful, Son House did two years there as well as Vernon Presley, Elvis’ father who did a year for writing a bad check for $4. Buka White did hard time there and was serving life for murder when in 1940, the governor of Mississippi granted him a pardon. White authored the song “Parchman Farm Blues.”

Tutwiler was to be our last stop of the day. It was getting late and we wanted to get to Clarksdale where we had reservation at the Hopson Inn – an old plantation that has upgraded its accommodations to include heating and air conditioning.

There’s a mural near what was once the train station, and this is the location where W.C. Handy once lay half asleep when he heard the strings of a guitar being played by a pocketknife and singing, “I’m going where the “Southern cross the dog.” These two cities – and I use the term loosely – came into play the first time W.C. Handy first heard the blues at the Tutwiler train station in 1903. Handy later adapted and published the song as, “Yellow Dog Blues.”

Today, Tutwiler’s population is too small to be mentioned in the AAA tour book, but there’s a sense of being somewhere of historical significance. Without this moment, the course of musical history would have changed dramatically. Handy wrote the blues scale, packaged it up and delivered it to the world. Without him and people like Alan Lomax, John Work, John Hammond Sr., H.C. Speir, who discovered and recorded many of these great bluesmen, and Gayle Dean Wardlow, and Steve Lavere, who retrieved the music and history from the brink of extinction and shared it, this music surely would have been lost.

The mural depicts some blues legends and history and scrawled on the last panel were the directions to the grave site of Sonny Boy Williams II.

Luckily, we had the guide book as a secondary resource or we would not have been able to find the site. As we headed down a desolate stretch of back road, we again saw the now too familiar sight of our two hell hounds standing by the side of the road watching us slowly pass.

Sonny Boy’s grave was situated down a steep hillside by a row of trees. It was adorned with some cheap plastic flowers and appropriately an old harmonica. As we retraced our steps back to the highway, our two dogs were still standing in their same spot. By this time, it had become a running joke with a biting sense of reality attached. This time we captured some video.

Clarksdale

This city of 20,000 is just 60-plus miles from Memphis and boasts some blues heavyweights beside being the site of the fabled crossroads. Muddy Waters was born nearby on the Stovall Plantation where he learned guitar from Son House. Junior Parker, John Lee Hooker and Ike Turner hail from Clarksdale. In addition, Bessie Smith died in Clarksdale at the city’s black hospital after a car accident just north of the city.

We passed the Hobson Plantation on our way into town and got our first glimpse of the night’s accommodations. Hopson plantation was the first site to use a mechanical cotton picker.

However, since it was still early afternoon, we decided to check out the Delta Blues Museum. Suddenly we found ourselves at the crossroads of highway 61 and 49—the intersection of the state’s two main highways.

However, since it was still early afternoon, we decided to check out the Delta Blues Museum. Suddenly we found ourselves at the crossroads of highway 61 and 49—the intersection of the state’s two main highways.

Like all good myths, no one knows where the actual crossroads that Robert Johnson sang about is located, but with its 20-foot high lighted blue guitars screaming out this location, it’s as good as any and definitely the most famous.

It’s interesting to note that it was blues man Tommy Johnson who actually claimed to have sold his soul at the crossroads – a story told most likely to scare the be-Jesus out of his little brother, Ledell. Also, a little Google search will provide good information on the source of the mischievous West African god Eshu who would grant life-changing wishes. By the 1930s, this legend had morphed into the devil and soul selling at the crossroads.

Located at 1 Blues Alley, in the old freight depot, is the Delta Blues Museum which boasts among its exhibitions the cabin where Muddy Waters was raised, as well as B.B King’s Gibson “Lucille” and a harmonica once belonging to Sonny Boy Williams II. The museum was worthwhile and while talking with a volunteer at the gift shop discovered that we shared the same hometown in Kansas and knew many of the same musicians.

Next, we hit Ground Zero, which is the juke joint once owned by actor Morgan Freeman and had lunch before heading back to the Hobson Plantation to get settled.

Blues legend Pinetop Perkins once called the Hopson Plantation home. Today, it houses a handful of old shotgun shacks that have been purchased for the surrounding area and renovated. We stayed in the flag-ship shotgun shack, the Robert Clay. Clay raised nine sons in this shack without the benefits of electricity or running water. In his waning years, he refused to leave the shack. When he passed away the boys discovered why he was so reluctant to leave. A whiskey still was hidden in the attic. Some of the copper tubing is still visible above the bathroom sink.

The room came equipped with an old upright piano as well as a small guitar and amp. Unfortunately, the guitar cord had a short. However, we still managed to unpack the guitar and mandolin from our luggage and make a little music before heading back to Ground Zero for the night’s entertainment.

It was jam night at Ground Zero and the band held together nicely, as a cast of characters took the stage. But what was most memorable was a group of visitors from Canada attending a small festival in the area. One gentleman, who looked like a used car salesman, sang from his guts, blew the harp like a man possessed and led the band through the changes like he’d been with the group for years. It was absolutely a show stopper.

Shortly before closing time, a group of young men at the bar engaged in a brawl that resembled a dozen couples dancing in close formation. The ruckus was short-lived and the victors stayed while the loser was carried to a waiting ambulance.

Later, as the bar closed and we were leaving we couldn’t help but notice that the ambulance was still in the middle of the street, the battled looser strapped to a gurney with his neck in a brace while the drivers joked with some of the very customers who were involved in the disturbance—some things never change.

Exhausted from days of driving and nights of juke joints, I was half dazed or half asleep when we came to a stop at the 61/49 Cross Roads. Looking at the car’s clock I realized it was midnight and my birthday. I commemorated the occasion by mumbling something about turning 61 at the Cross Roads and as the light turned green, we headed back to our room where I immediately fell into bed.

If Walls Could Talk

The next morning, we stopped by the Riverside Hotel, the place where Bessie Smith, Empress of the Blues, passed away after being involved in an early morning auto accident north of town on Sept. 26, 1937.

Controversy over the circumstances surrounding Smith’s death has raged virtually since that night in question. John Hammond, Sr published a story in Downbeat magazine stating that Smith had been refused medical assistance at the city’s white hospital and bled to death. In 1959, this myth was further compounded when famed playwright Edward Albee introduced his work, “The Death of Bessie Smith.”

Those with knowledge of the incident and of the racial sentiment of the town say that no ambulance driver would have taken a black patient to the white hospital, and besides the hospitals are less than half a mile apart. Hamond publicly stated his error; however, the myth persists and its not uncommon even today to see the story incorrectly retold.

The hotel is graced by a historical marker, and as we were filming, an older gentleman in a robe and pajamas asked what we were doing. He seemed happy with the answer and went back inside. Several minutes later he reappeared and invited us inside.

He introduced himself as “Rat” short for Frank L. Ratliff, proprietor of the Riverside. The hotel had originally been managed by his mother. The walls inside are lined with photographs of all the great blues musicians who have stayed there and soon he was telling us who had occupied each room—Sam Cooke, the Blind Boys of Alabama. Even Robert Lockwood, Jr. had left a suitcase there unclaimed. The basement, he said, is where Ike Turner had cut the demo for Rocket 88—notably the first rock & roll record ever recorded.

So enraptured by Rat’s stories of the hotel and the legends who stayed there that it was only after leaving that we realized we had not shot any video of this fascinating gentleman. He was typical of the people we met along our trip who were always more than willing to talk about the blues and people who made it famous.

Memphis Women and Chicken

Since my stupor from the night before had dulled the dawning of my birthday, we celebrated with a trifecta and celebrated the day when we were 61 miles from crossroads on highway 61, going 61 mph and I, of course, was 61 years old. We hoped against the odds that it might be 61 degrees outside, but it was just too much to hope for.

We met the wives and checked into a gorgeous southern gothic type condo just off of the celebrated Beale Street and spent the next two evenings experiencing the sites and sounds—Polly’s fried chicken and the music of Beale and the home of W.C. Handy.

I was greeted at the condo with a chocolate cake clad with a plastic car cruising down the road and the state highway 61 sign emblazoned at the top. Of course, we ate up the road.

During the day, Jamey and I visited Sun Studios and the Stax Museum, both of which were more than worthwhile. To stand where Elvis sang his first recorded song, and to learn that Johnny Cash wrapped a dollar bill around his guitar neck to give it a rhythmic chunk on “I walk the Line” because the Grand Old Opry would not allow drums, was priceless.

The Stax museum paid tribute to Otis Redding and the great house band of Booker T and the MGs featuring Steve Cropper and Donald “Duck” Dunn.

Returning to the condo on our last afternoon in Memphis, we came to a sudden stop outside our front door and gave a unison groan. Standing to the side of the building were two large unidentifiable dogs – one light, one dark – standing motionless and staring at us. It was at least the sixth pair of mutts we’d seen since the trip began and added an eerie sense to our final Memphis afternoon.

For days we had been standing on the shoulders of Giants, and by traveling Mississippi south to north we had followed a linear path of our musical history from the days of field recording right on through to the ‘50s and ‘60s and into today.

As we readied to return to our respective homes, I felt a connection to the music as never before. The sentiment might best be described by my blues traveling partner when he said that he could sing these blues songs with a new understanding. When you talk about the crossroads, or where the southern cross’ the dog, or about goin’ down the Rosedale, there is now an emotional, mental and spiritual image to support the words.

On the way home, it was with renewed respect that I again listened to my favorite old blues tunes and realized that there’s truth in the fact that, you don’t know where you’re going, if you don’t know where you’ve been.

Copyright © 2020 Doug Webb

_________________________________________________________

Note: The trip to the Mississippi Delta took place in 2008, and was updated in January of 2020. The primary information source for our Delta Blues Cruise was the second edition of “Blues Traveling” by Steve Cheseborough. In addition, we traveled with AAA Tourbooks and an assortment of maps and google data.

_________________________________________________________

Doug Webb is a member of the Outlaw Blues Society

Doug Webb is a member of the Outlaw Blues Society

_________________________________________________________