‘The Elmore James Story’ Marking the 20th Anniversary of his death – by Alan Balfour from the British Blues Archive

Sixty five years ago, Elmore James was born in Richland, Mississippi, the illegitimate son of fifteen year old Leola Brooks. Twenty years ago he died in Chicago. Of his forty five years of life, only the last twelve brought him any measure of repute in his chosen profession of bluesman. His greatest acclamation was to come posthumously, from middle class whites who were culturally so far removed from Elmore’s world that any astonishment he might have felt when interviewed by two Frenchman in 1959 would surely have been as nothing, had he been able to experience the international adulation he received when it was too late for him to benefit.

Sixty five years ago, Elmore James was born in Richland, Mississippi, the illegitimate son of fifteen year old Leola Brooks. Twenty years ago he died in Chicago. Of his forty five years of life, only the last twelve brought him any measure of repute in his chosen profession of bluesman. His greatest acclamation was to come posthumously, from middle class whites who were culturally so far removed from Elmore’s world that any astonishment he might have felt when interviewed by two Frenchman in 1959 would surely have been as nothing, had he been able to experience the international adulation he received when it was too late for him to benefit.

Officialdom was not greatly concerned to document the childhood of rural black Americans of that era, and it is only thanks to some assiduous and painstaking research by Gayle Dean Wardlow and the late Mike Leadbitter that we know that Elmore James’s birth took place on January 27, 1918. Local rumour hinted that his father was a farmhand named Joe Willie James, who set up home with Leola Brooks shortly after the birth. Various “cousins” have recalled that the family moved along Mississippi’s 5l Highway from plantation to plantation – Lexington, Goodman, Durant, Pickens – seeking work. There is no reason to suppose that Elmore James’s early life was much different from that of his contemporaries, so from early childhood into adolescence he was probably working from sunup to sundown crop picking – in the fields. Crucially, however, a distant cousin recalls that the boy was always passionately interested in making music, first with a broom wire strung on the shack – later picking out tunes on a home made – hyphen instrument that comprised a lard can with three strings.

By the time Elmore was a teenager, the family had moved to Goodman, at which time a second cousin, John Junior Gueston, remembers him playing Saturday night dances in nearby Franklin, accompanying himself with a six-string guitar on numbers like Dust My Broom. At this time, he had not yet adopted the bottleneck technique which was to become almost synonymous with his music in later years. Another, older cousin, fellow blues artist Homesick James, recalls that Elmore worked dances and barrelhouse functions throughout the Delta from about 1932, making quite a name for himself. Despite the travelling away from home that must have been entailed, he was still with his parents in 1937, aged 19, when the search for better work took the family to Belzoni, deep in the Delta. The pattern of sharecropping with frequent moves between plantations continued, but farm work obviously bored Elmore, as much as it did most young men of his age, and with each move he became more convinced that the sharecropper’s life was not for him. His parents, perhaps in reaction to these signs of restlessness, adopted an orphan, Robert Earl Holsten, as a brother for Elmore. The two young men shared a talent for making music, and entertaining in the juke joints of Belzoni led to consequences doubtless unpalatable to Joe Willie and Leola James – notably bootleg whiskey and loose women. In the same year, 1937, Elmore embarked briefly on marriage to a local girl, Josephine Harris, an experience which only heightened his restless longing for the footloose life of a musician. It is not to be wondered at, then, that two bluesmen he encountered during this momentous year made a profound impression on him. They were Robert Johnson, a musician of some local repute who had also recorded for the American Record Company and harmonica player Alec “Rice” Miller, as yet unrecorded but already embarked on his colourful career as a bogus Sonny Boy Williamson. These two, hard living and hard drinking, bluesmen embodied everything that Elmore longed to be, and Johnson’s technique of playing guitar with a bottleneck – especially on I Believe I’ll Dust My Broom – had a more immediately musical effect on him, although Johnson left the Belzoni area soon after their meeting.

Two years later, and still only twenty one, Elmore James had moved to the Daybreak Plantation, where he and his lost brother played lead and rhythm guitar respectively in a small combo. This band, which needed the extra instruments to cut through the din at country suppers, was completed by Precious White (saxophone), Tutney Moore (trumpet) and Frank O’Dell (drums), and entertained at such diverse and exotically named venues as the Peacock Inn and the Harlem Theatre, this one in Hollandale. Robert Holsten later recalled that the band tended to confine its activities to the winter months, when the lack of work in the cotton fields made what small amounts of money the gigs paid that much more welcome. By this time, the wanderlust had really gotten to Elmore, and he would take off at weekends, usually travelling to Arkansas to maintain his friendship with “Sonny Boy Williamson”, who was acquiring a measure of fame for himself via a fifteen minute radio spot on KFFA, advertising the Interstate Grocery Company’s King Biscuit Flour between the music. Very probably, Elmore was mildly jealous of this notoriety, and would at every opportunity slip off from Belzoni to see whether Helena held any prospect of becoming a full time musician like Sonny Boy.

All these dreams were dashed, however, by America’s involvement in the Pacific conflict, and the consequent demand for servicemen. On July 24, 1943, Elmore James found himself drafted. His military service took him to Guam in the West Pacific as a member of the US Naval Reserve. On November 28, 1945, two months after the end of the Second World War, he was honourably discharged, and headed straight back to Belzoni. He found that in the intervening three years his parents had moved north to Chicago, while his half-brother had returned to Leola Brook’s home town, Canton, Mississippi, to open a radio repair store. Elmore chose to join Robert Holsten in Canton, where he stayed for a year: at this time doctors diagnosed a heart condition, which forced him to undergo hospital treatment in the state capital Jackson, still only twenty eight years old. However, he slowly began to pick up his musical career again, seeking out his old friend Sonny Boy Williamson in Helena, Arkansas and making the acquaintance of Sonny Boy’s drummer, James “Peck” Curtis, who provided Elmore with a “pied a terre” when he visited Helena .

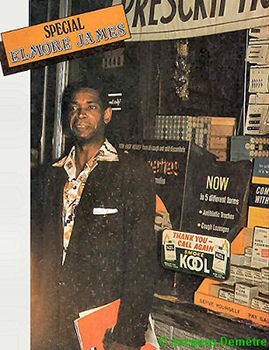

By 1946 Elmore had moved back to Belzoni, got married again, to Georginna Crump, and was playing at a barrelhouse called Webber’s Inn. These gigs brought him enough local fame that Sonny Boy was moved to offer Elmore irregular spots on his Talaho Show, a half hour programme recorded at O.J. Turner’s Drug Store in Belzoni, for broadcasting to Turner’s potential customers from radio stations in Yazoo City or Greenville. Five days a week Sonny Boy would sing blues, and on Sundays gospel songs, which must have sounded strange with Elmore’s slide playing backing him, and the show drew many listeners, incidentally achieving its sponsors’ main aim, of boosting the sales of the eponymous patent medicine. The main effect on the musicians as might be expected, was to enhance the reputation of Sonny Boy, the star of the show, and in 1949, after two years with Talaho, he was headhunted by another “remedy”, Hadacol, and left for West Memphis to broadcast over KWEM at a more lucrative rate. However, the Talaho show had given Elmore the opportunity to meet and play with bluesmen of the stature of Arthur Crudup, Johnny Temple and Willie Love, and the latter, who had a daily programme on WDVK, Greenville, sponsored by a consortium of local business men, brought Elmore into his band, the Three Aces. This association was to prove fruitful, for Love was a close friend of Sonny Boy’s and, although based in different towns, Love and “Rice” frequently met up, thus maintaining the latter’s friendship with Elmore, which was shortly to lead to a new phase of Elmore’s musical career.

In 1950, by then very much hampered by his heart complaint, Elmore James moved to Canton in the wake of a rumour that Lillian McMurry, who owned furniture and record outlets in nearby Jackson, was trying to locate Sonny Boy Williamson in order to record him for her newly formed Trumpet label. Elmore saw possibilities of teaming up with his old friend in this venture, and indeed, on January 5, 1951, Sonny Boy, Willie Love, Joe Willie Wilkins, a guitarist, and Elmore James went to the studios of the Diamond Record Company to cut their first titles for Trumpet, Eyesight To The Blind and Crazy About You Baby. However, if Elmore is present at this session it must surely have been as a spectator rather than participant for the one, barely audible guitar, has all the trade marks of Joe Willie Wilkins. [Trumpet session files and information from Mrs. McMurry has since shown that a remake session was held after the masters from the first session was destroyed in a fire. Discographies show these two titles from the first session as having been released on a Trumpet 78; however, as all reissues of these titles use the versions made at the remake session (at which Elmore James did not participate) it is doubtful if the earlier recordings were actually issued. ]

From the recollections of Lillian McMurry and Sonny Boy Williamson, it appears that Elmore made a number of visits to the Trumpet studios following that session and that during 1951 Mrs McMurry repeatedly asked him to record his popular Dust My Broom, for release under his own name. The prospect of doing this apparently made Elmore so nervous that finally he was hoodwinked into “rehearsing” the song with Sonny Boy and Frock O’Dell, McMurry surreptitiously left the tape recorded running. This story has seen much circulation, but has been proven to be mythical; for instance Gayle Dean Wardlow’s postscript to his and Mike Leadbitter’s “Canton, Mississippi”]. In August, 1951, therefore, Mrs McMurry had a one-sided record, for nothing else was forthcoming from Elmore; when it was released in October, Dust My Broom was backed with a fine version of Catfish Blues, credited to Elmore James but actually by the obscure Bobo Thomas who had been recorded by Trumpet earlier. Over the next six months, Dust My Broom made a considerable impact on the black record buying public, and by April, 1952 had reached as high as number nine in the “Billboard” R&B charts. Elmore, with his heart complaint requiring constant hospital attention, didn’t really want to record again, and used the royalties from his hit to give up his day job. However, since Elmore failed to show any further interest in recording for Lillian McMurry, she attempted to find a replacement in the seasoned bluesman Arthur “Big Boy” Crudup whom she recorded for Trumpet as Elmer James. In January 1952, though, Joe and Lester Bihari virtually “stole” Elmore from under Mrs McMurry’s nose when they recorded him accompanied by Ike Turner while on a field trip through Jackson, with the result that the Biharis had to make a hasty flit from town. However, they met up again with Elmore three months later at a safe distance from Jackson, in Clarksdale, Mississippi during another field trip with Ike Turner and it would seem that at one of these encounters Elmore was persuaded to go to Chicago to record. Doubtless the prospect of seeing his mother again was a factor in his decision.

Once in Chicago, he joined the local branch of the American Federation of Musicians, and moved in with his uncle. A fellow lodger was Howlin’ Wolf, through whom Elmore got acquainted with piano player Johnny Jones. Around October, 1952, the Biharis recorded Elmore and the Johnny Jones Band – tenor saxophonist J.T. Brown, bassist Ransom Knowling and drummer Odie Payne Jr. – for their new Meteor label, the first release being, perhaps predictably, a variant of the “Broom” theme called I Believe. This duplicated the chart success of the earlier version, but the only other release on Meteor failed to score. This may have been the result of market saturation for, even as I Believe was still getting into the charts, Elmore and the Jones aggregation had jumped labels to record five titles for Chess. The topside of the only issue was, once again, a version of Dust My Broom entitled She Just Don’t Do Right released on Checker, this time sung very much in the style of the big band shouters and with J.T. Brown’s tenor dominating the mix. The contract breaking was followed by a rapid return to the Biharis, this time on their Flair label. The early releases by Elmore James and (inevitably) the Broom Dusters on Flair had a marvellously energetic co-ordination, the result of exacting standards set, probably, by the A&R men rather than the artists. The end product had to be just right – on April 1, 1953, a day’s work produced only three songs, but at least eighteen takes.

In October, 1953 Elmore and the band revived their contract breaking habit to do some work for Ahmet Ertegun’s Atlantic label. The previous May, Ertegun had made the experiment of recording one of his stars, Big Joe Turner, in New Orleans with local musicians. The combination had worked extremely well, and the possibility of combining Big Joe with the Chicago style suggested itself as another gimmick that might sell records. As a result, October 7, 1953 saw Joe Turner and his Blues Kings (who were Elmore and his Broom Dusters!) cutting T.V. Mama and Oke-She-Yoke-She-Pop. T.V. Mama featured slide playing of great sensitivity from Elmore, bringing a more lyrical tone than was his wont to the Mississippi/Chicago riff of Dust My Broom and marrying it to Joe Turner’s Kansas City blues shouting with unexpected congruity. Two days later, Elmore and his men returned to Chicago’s Universal Studios, this time without Big Joe, and pianist Johnny Jones took the vocal spotlight. Four items were recorded, but only two released, and not for another twenty years would anyone hear the result of an experiment carried out that October day – Elmore James playing acoustic slide guitar on a number called Chicago Blues. Less like the Chicago blues of its time the performance could not have been: it is probably the closest idea we shall ever have of what Elmore sounded like in the years before he was a recording artist.

Soon after these sessions, Elmore took off to Canton, probably to be in easy reach of the Jackson hospital that was treating his heart complaint, and possibly to be elsewhere when the Bihari brothers found out about what had been going on. However, the Biharis tracked him down early in 1954, and three songs were recorded in Clarksdale, backed by Ike Turner’s band. The next session, in March, was a hastily organised affair, recorded at the Club Bizarre (!) in Canton; the results were very muffled in sound, and it was probably for that reason that the sides from two much earlier sessions were chosen for release in the same month.

It’s not clear how Elmore spent the remainder of 1954. He had acquired both a manager, Otis Ealey, and another wife, Janice, but his relationship with the former lasted much longer than that with Janice, who got the treatment accorded to earlier wives – desertion. By May 1955, Elmore was back in the studio for Modern, this time in their “movie town” location of Culver City, a suburb of Los Angeles, in the unlikely company of saxophonist Maxwell Davis. Davis led his own band, and dabbled in production, working mainly on the West Coast and with big band singers. This session with a slide playing Chicago bluesman was rather disappointing, with Davis’s attempts to emulate J.T. Brown on numbers like Standing At The Crossroads lacking the punch of the Broom Dusters. A few months later came a session in New Orleans. The Biharis may have been hoping to emulate Ahmet Ertegun’s success in pairing Big Joe Turner with Crescent City musicians, but if so the experiment was, at the time, a failure, for the local artists’ laid-back approach just wasn’t compatible with Elmore’s attacking style. On one title a vocal group was brought in, with very unfortunate results.

Record sales for Elmore were by now in the doldrums, and a session in Chicago the following January turned out to be his last for the Biharis. The whole day only produced two titles; one song required twenty two takes, mostly false starts. Elmore’s health problems may have combined with difficulty in mastering material to cause this low output. For the rest of 1956, he went back to working the clubs, playing regularly at Sylvio’s with Johnny Jones, J.T. Brown and usually his cousin Homesick James Williamson on bass guitar. The fast life of the previous years’ state to state recording sessions was taking its toll, though, and early in 1957 Elmore, only just thirty nine, was hospitalised yet again following a second heart attack. Despite all these setbacks, he was still a big enough name on the Chicago music scene to be signed by Mel London for his new enterprise, Chief Records. Of the two sessions resulting, the first produced five superb numbers, the Broom Dusters being augmented by the guitars of Eddie Taylor, Homesick James and Wayne Bennett, all, reputedly, playing through one amplifier, while on the second Wayne Bennett took the lead guitar role. The result was two very polished numbers, neither of which featured Elmore’s slide work. From reports of those witnessed Elmore’s club appearances during 1957 it would seem that he had taken to being solely a vocalist, leaving the guitar duty to members of his band, except when called upon to perform Dust My Broom.

Despite this very impressive comeback, Elmore’s health forced him back to Jackson in 1958, where he found work as a disc jockey on WRBC. The settled life suited him no more than before, though, and he returned north to Chicago in search of his band. Here, Carolina born Bobby Robinson located Elmore and recorded him for his New York based Fire label, setting up a session in Chicago towards the end of 1959. This produced a version of an instrumental which Elmore had been featuring in the West Side clubs. That same year, Belgian Georges Adins saw him performing the tune, and reported that it was “at that time one of the favourite numbers of the crowd and Elmore used to play that instrumental number for fifteen minutes or more”. The title of the recording, Bobby’s Rock, may have been Elmore’s recognition of Robinson’s work as producer, or a flight of egotism on Robinson’s part; ten years later a tape box with the title Elmo’s Rock came to light. However, popular as that number may have been on the club circuit, it was Elmore’s second Fire release, The Sky Is Crying, which was to provide him with his first R&B Top Twenty in seven years, when it crept into the charts in May 1960 some six months or so after its issue.

Through his long association with the Chess family, Bobby Robinson procured a session for Elmore in April 1960. Of the four titles known from this date, only two were issued at the time. The Sun Is Shining was a marvellously intense performance, on which Elmore wrung every drop of emotion from each word, much in the manner of a “straining preacher”, while the flipside tore along with the “Broom” riff at a frantic pace. The two unreleased numbers were T-Bone Walker’s Stormy Monday, done to the tune, and in the style of, The Sun In Shining, possibly because ideas were thin on the ground, and a lightweight item called Madison Blues, which had not much to do with blues but quite a lot to do with a then current dance craze, “The Madison”, as sparked by Al Brown’s Tunetoppers hit record on Amy of spring that year.

Elmore did not stay with Chess, but returned to the Bobby Robinson stable when The Sky Is Crying broke nationally, recording a vast amount of material for him in 1961 and 1962, mainly in New York, and usually with local brass and saxophone session men (among them baritone player Paul Williams of Hucklebuck fame), providing a sympathetic accompaniment. At the other extreme, Robinson experimented with a backing consisting only of a rhythm section – piano, bass guitar and drums. On a couple of numbers, he even dropped the piano. For a session in New Orleans, rather than perpetuate the Biharis mistake of using local musicians, Elmore’s working band was brought down from Mississippi, harmonica player Sammy Myers providing splendid backup on Look On Yonder Wall. Only a few titles from the quantities of material taped by Bobby Robinson were ever issued as singles, and then mostly posthumously.

At this time, for reasons that have never been satisfactorily explained, Elmore became embroiled in a dispute with the Musician’s Union, who prevented him from broadcasting and recording. Disillusioned, tired and sick, he returned to Jackson in 1962, to live in semi-retirement. By May, 1963, however, Chicago disc jockey Big Bill Hill, having cleared up Elmore’s problem with the union, paid for him to return to Chicago. Arriving on 19th May, he was back, playing in the clubs with Homesick that same evening, only to die on 24th May following a third heart attack. Some three or four hundred people attended the funeral in Chicago, including musicians Willie Dixon, Sunnyland Slim, J.B. Lenoir and Jazz Gillum, and label owner Paul Glass, who had been about to record Elmore for USA. Big Bill Hill paid for the funeral, and for the body to be returned to Jackson. In England, a magazine that had only started publishing the previous month, “Blues Unlimited”, reported Elmore’s death in its columns.

Twenty years on, that same magazine has been primary in adding to our knowledge of the man and his music, and any retrospective on Elmore James must be largely derivative of the work of others (this article being no exception). The early efforts of Georges Adins, Jacques Demetre and the late Marcel Chauvard (whose 1959 interview formed the basis of most articles for ten years or so), and the exhaustive research conducted in the 1970s by Gayle Dean Wardlow and the late Mike Leadbitter, have given us a full biographical portrait of Elmore James. The only area still in need of detailed research is his discography and the one published here will hopefully be a step on the road to a proper chronology. We must hope that when Ace Records in England have unravelled the mass of information on the tapes and in the files of the Biharis, and when more information is forthcoming from Bobby Robinson, our understanding of how Elmore James worked with his bands and producers to capture his marvellous music – for the posterity he never knew about – will be that much clearer.

Alan Balfour, Soul Bag 94 (May-June 1983)