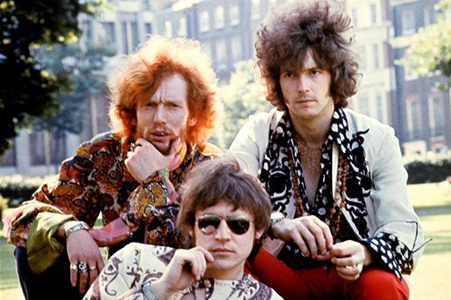

“Fresh Cream” – Cream

Recorded August–November 1966 at Rayrik & Ryemuse Studios, London

Released 9th December 1966 on the Reaction label Prod: Robert Stigwood

“What’s this?” I hear you say, gentle reader. “Cream? Weren’t they the psychedelic rock band who invented heavy metal? What are they doing here, despoiling my collection of British Blues Classics?” But strangely, however they might have turned out, Cream was intended to be a Blues Band, at least by founding member Eric Clapton.

American Blues Legend Buddy Guy had been playing London gigs with a trio line-up, and young Eric was mightily impressed. “I’d seen Buddy live” he recalled, “and it was unbelievable. He was in total command, and I thought, ‘This is it.’ It seemed to me you could do anything with a trio – at least if you were a genius and a maestro like Buddy Guy. I was suffering from delusions of grandeur in that direction.”

Ginger Baker, then drummer and acting manager for the slowly disintegrating Graham Bond Organisation, remembered, “”Eric used to turn up at Graham Bond gigs and sit in. (Wouldn’t I like to have seen that! – Sneaky Stevie) I didn’t realize who he was. I was totally unaware that he had this huge following. Originally Cream was my idea. I told Eric I was getting a band together, and would he be interested? “

There was only one fly in the ointment, Clapton wanted Jack Bruce as bass player. The two had played together when Jack did a short stint as bassist with Mayall’s Bluesbreakers, and again in Powerhouse, a studio project for Elektra producer Joe Boyd which also included Manfred Mann’s Paul Jones, and Stevie Winwood and Pete York from the Spencer Davis Group. But Eric remained blissfully unaware of the tremendous history of animosity between Bruce and Baker.

Clapton suggested Bruce as bassist for the new group, but Baker recoiled at the idea, saying, “No, what did you have to go and mention him for?” Pressed further, Ginger explained, “We don’t get on very well at all,” which was something of a massive understatement, considering the rumour that he’d threatened to knife the bassist if he didn’t leave the GBO. But Clapton wouldn’t be swayed, if Ginger wanted him, then Jack had to be part of the package.

And so, once they’d dispensed with the suggestion of calling the band “Sweet & Sour Rock’n’Roll,” Cream was born. But although these were considered the UK’s most talented Blues players of the day, Clapton failed to achieve his aspirations in the band. “Once I stepped into the reality of trying to realise my musical vision with Cream, it just disappeared,” he explained. “It was meant to be a Blues trio. I just didn’t have the assertiveness to take control. Jack and Ginger were the powerful, dominant personalities in the band; they sort of ran the show and I just played. In the end, I just went with the flow and I enjoyed it greatly, but it wasn’t anything like I expected at all.”

And the group’s debut single wasn’t like anything the public were expecting, either. In October 1966 Cream released Bruce’s beautifully arranged “Wrapping Paper,” co-written with lyricist Pete Brown. It was a warm, wistful number with rolling piano and a lazy feel reminiscent of The Lovin’ Spoonful’s “Daydream,” which had made no. 2 in the UK charts earlier that year. Delightful as it was, it bore no trace of any discernible Blues influence, and the often outspoken Mr Baker later judged it as “the most appalling piece of shit I’ve heard in my life.” Nonetheless it managed to limp up to no.34 in the UK charts.

However, the LP that followed it two months later did something to reaffirm public expectations, as five of the ten titles were Blues covers, and one of Bruce’s songs was in the deliberate style of a slow twelve-bar, casting the trio much more in the role of a Blues Band. But this bias was not to be repeated on later LPs, and though Blues remained part of their repertoire, the trio went on to find themselves at the forefront of the newly-emerging genre which we now call Blues/Rock, alongside bands like Led Zeppelin and The Jeff Beck Group, coincidentally both formed by other ex-Yardbird guitarists.

Bruce emerged clearly as the band’s main singer and songwriter, taking the lead again on their second single, the far stronger “I Feel Free.” Still melodic, but featuring a driving beat, punctuated by stop-time bridges, with layered vocals and a soaring “woman tone” solo from Clapton, it far better reflected the band’s powerhouse style, and the song worked its way up to no.11 in the Top Twenty.

The album’s sleeve notes are provided by “Mayfair Public Relations Ltd.” and seem to waver between hyperbole and fantasy – Eric Clapton “originally a rustic”? Ooo-arrr! Nonetheless I repeat them here as they originally appeared.

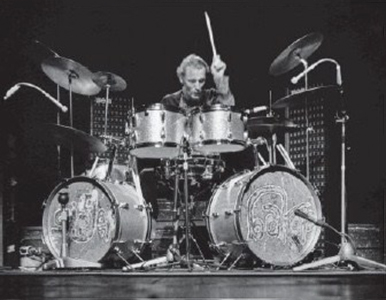

“ GINGER BAKER (drums/vocals) is undoubtedly one of the greatest drummers in Europe today. He has played or recorded with most ‘name’ groups and for three years was the driving force behind the Graham Bond Organisation. His unique rhythmic patterns and remarkable technique make him Britain’s most outstanding drummer.

JACK BRUCE (bass guitar/harmonica/vocals) was featured bassist/vocalist with Manfred Mann, and previously played with Graham Bond and John Mayall. Jack is a fiery musician of great feeling and the sounds he produces from his six-string bass and harmonica are quite revolutionary.

ERIC CLAPTON (guitar/ vocals) epitomises all that is ‘blues.’ From far shores he is hailed as brilliant, and he is truly a great guitarist and personality. Originally a rustic, Eric pursued his musical ideals and became a figurehead with The Yardbirds and John Mayall.

It all started four months ago as rumours. It seemed hard to believe that three such musical giants as Eric Clapton, Ginger Baker and Jack Bruce could be joining together. Soon it became a reality, CREAM were formed and here they are.

This album is made up of pure fresh Cream. Digest and enjoy it, but do not worry too much, there is a lot more where this has come from…CREAM”

SIDE ONE:

Trk 1: “N.S.U.” Aaah, the joys of male camaraderie! You join a new group and first thing you know, one of your band-mates has written a song dedicated to your current sexually-transmitted disease. This, it seems, is how ‘N.S.U.’ ( short for ‘non-specific urethritis’) came into being. Pounding toms and lightly tinkling guitar introduce an almost whispered verse about the joys of being a guitarist with the clap, before the band explodes into a sequence of vocal harmonies and power chords which breaks down, re-starts and builds up again until Eric finally lets fly with a biting solo.

The mix is murky, but I’m pretty sure there’s a sustained guitar note filling out the sound in the background, and that’s a trick that’s repeated on later tracks. The last set of harmonies resolves to a gentle, melodic ending which tails off and fades just as Ginger puts his sticks down. The verse itself is nursery-rhyme simple, and the number’s really little more than a vehicle for Clapton’s sizzling guitar, but overall it’s an interesting combination of forcefulness and melody, quite powerful without being “heavy.”

Trk.2: “Sleepy Time Time.” Written by Bruce with lyrics by then-girlfriend Janet Godfrey, this is in the mode of a stop-time slow blues, though the sequence is unusual – it goes up to the ‘four’ twice, turning it into a 16-bar Blues. Bruce and Baker inject some little tricks of timing which can deceive the listener into thinking the breaks are longer than they really are, but I’ve counted the bars (yes, really, like I’ve got nothing better to do!) and they’re all even. Bruce’s vocals are very subdued on the verse, but rise up strongly on the chorus, which seems to be double tracked. Clapton’s guitar is double-tracked too – the tone and style is reminiscent of ‘Telephone Blues,’ a track he recorded with Mayall on the B-side of ‘I’m Your Witch Doctor,’ produced by Jimmy Page. Undeniably a British Blues, and quite an original one, too, this gets top marks.

Trk.3: “Dreaming.” Delicate and lilting are not terms usually reserved for power trios, but they apply to this unexpectedly pretty tune of Bruce’s, which at 2.02 is the epitome of short and sweet. Gentle-voiced Jack echoes himself in the verses, and there’s a brief solo section where guitar and bass follow each other languidly up the scales before returning to the middle 8. It’s not Blues, but I like it. The overall feel is surprisingly smooth and lush, probably not one that would have inspired many Heavy Metal bands.

Trk. 4: “Sweet Wine.” This tribute to wasted time was written by Baker with Jacks wife-to-be, Janet Godfrey. Originally the secretary of the GBO Fan Club, she’d already co-written two songs with Bruce for the band’s ‘Sound Of ’65’ LP (also in our collection of Classics.) Like ‘N.S.U.’ this features Jack on lead vocal, and relies again on the strength of combining harmonies and power chords, held together with Baker’s inimitable drum fills. Eric contributes a fiery double (triple?) tracked solo, which again uses feedback and sustain laid back in the mix to fill out the sound of the trio.

Trk.5: “Spoonful.” Jack’s in passionate voice on this Howlin’ Wolf cover, and he allows himself the luxury of overdubbing harp on the riffs and behind Eric’s shredding, feedback drenched solo. But rather than being “backing musicians,” what Bruce and Baker are doing behind Clapton is just as dynamic and exciting, and all three play with tremendous force and fluency. More importantly, they don’t forget when to bring the damper down, so the tension in the song is not lost in overkill. The sound they create here will soon give birth to Blues/Rock in all its Stadium-filling horror, but for now they’re just three young white guys playing a new and very electric kind of Blues. Simply terrific.

SIDE TWO:

Trk.1: “Cat’s Squirrel” is credited to “Trad. Arr. S. Splurge,” thus ensuring no royalties would go to the rightful composer, Isiah Ross. Dr. Ross (The Harmonica Boss) recorded Cat Squirrel (sic) for Sam Phillips on Sun in 1953 as a one-chord acoustic Blues with a washboard accompaniment. In 1961 he re-cut the song for Fortune, in an almost-rockabilly version, as Dr. Ross & The Orbits, so it’s hard to say which one would have been the influence on this arrangement, though both use the same repeating rhythm guitar figure as a focal point. Here Cream play the number as an instrumental, featuring tight, unison guitar and harmonica, and on hearing it in this presentation I’m struck by the resemblance to Muddy Waters’ “You Need Love.”

Although it’s taken at a different tempo, Ross’s 1953 Sun recording has a similar verse structure to Muddy’s 1950 ‘Catfish Blues’ (aka ‘Rollin’ Stone.’) Muddy seemed to like that structure, and revisited for his 1951 ‘Still A Fool’ (aka ‘Two Trains Running’) and again, with a repetitive backing riff, for his more uptempo 1953 recording of ‘She’s Alright.’ In 1962, after the success of ‘You Shook Me’ a vocal he overdubbed on an Earl Hooker instrumental, he repeated the process with ‘You Need Love,’ the song that eventually became the inspiration for Led Zeppelin’s famous (notorious?) ‘Whole Lotta Love.’ Whether Hooker had Muddy’s previous recordings in mind when Leonard Chess asked him to cut the track, I can’t say, but presenting Cat Squirrel in this form certainly highlights some of the similarities.

Meanwhile, back at the track, there’s a quick chorus of “alrights” from an acapella Jack before Eric launches into his solo (though it sounds like it’s been done in two takes which overlap, so one’s clicked out and rather clumsily replaced by the other.) The guitar’s punctuated by Jack’s harp flurries, and they return to the verse and the repeated rhythm guitar figure, before it all disappears into a fade out ending. The result is a striking and rather unusual Blues instrumental, which was also recorded by Jethro Tull in 1968, and reprised by super-speed ex-Tull guitarist Mick Abrahams in his later band Blodwyn Pig. But where the Cat got his apostrophe from, nobody knows!

Trk. 2: Robert Johnson’s “Four Until Late” is a rather lightweight offering from Clapton, his only solo vocal here, and a fine example of how he wasn’t ready to become Buddy Guy. It’s delivered with something like a country feel (must be the rustic in Eric coming out!) while Bruce adds harmony vocals and harmonica, and Baker sounds like he wishes they’d chosen something more exciting. But in reality, it’s a neat and tidy, rather appealing re-arrangement of an otherwise overlooked Johnson number, a fine piece of British Blues, and well worth a listen.

Trk. 3: “Rollin’ and Tumblin'” takes the 1950 Baby Face Leroy Trio recording as a template, featuring no bass or second guitar, but relying on thunderous drums to carry the infectious rhythm. Eric’s shorn of solos here, and the accent is on Bruce’s harp, which is both strong and spirited, and plainly amplified – quite a novelty among home-grown Blues recordings of the day, though Jack had the benefit of backing British harmonica superstar Cyril Davies during his time with Blues Incorporated, so I dare say he picked up a trick or two. Very much in the mold of the original, it captures the raw, uninhibited feel with more success than Fleetwood Mac’s ‘Rambling Pony’ and shows the band taking their Blues roots very seriously.

Trk. 4: “I’m So Glad.” Gladness is a fairly unusual theme for a Blues of any kind, especially so given the contradictory lyrics and the mournful quality of Skip James’ voice, but Cream turn it on its head and make it seem quite joyful. Based on James’ 1931 Paramount recording, this re-arrangement relies on the descending chords of his mid-way guitar figure and features some rather luscious layered harmonies ( I think they’re all Jack) before Eric flies off into a blistering solo, with Bruce and Baker keeping a busy beat behind him. A very tuneful offering, but still Bluesy, I’m glad to say!

Trk.5: “Toad.” A riffy kind of tune gives way to a rather free-form jam with Bruce flying up his fretboard while Eric feeds back. Then all of a sudden it’s a drum solo. Now I understand Ginger Baker’s pretty much the finest drummer in the country, he’s often said so himself and who am I to doubt him? But I’m too much of a guitarist to get excited about this. With apologies to the Duke of Gloucester: ‘Another damned drum solo! Always thump, thump, thump! Eh, Mr Baker?’ 😉

Now at the tender age of sixteen, I was already a fan of both the Graham Bond Organisation and John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers, and I remember avidly awaiting this LP’s release, but finding myself somewhat underwhelmed when it arrived. Maybe I’d expected it to have some of the same qualities as the GBO or BB’s, but with neither Bond nor Mayall involved that wasn’t really likely.

The thing it does have, however, is Clapton playing like a veritable demon, serving up incandescent solos on a platter of angry feedback. By the time Cream had switched labels to Atlantic, his studio work had become much tidier and controlled, and even his playing on the famous “Live at the Fillmore” tracks on Wheels Of Fire can’t match the ferocity he displays here. It’s not Blues as we know it, Captain, but it still ticks enough of my boxes to qualify as a Classic British Blues Album. Give it a listen and see what you think.

And while we’re on the subject:

There have been an awful lot of claims laid at Cream’s door over the years, so I’d like to put my own historical perspective on some of them. Firstly, they’re often named as “the original power trio,” which ignores the contributions of earlier R&B bands using the same format such as The Big Three. Signed to Beatles manager Brian Epstein, they were described as “one of the loudest, most aggressive and visually appealing acts” to come out of the Liverpool scene. The Pirates, Johnny Kidd’s backing group, also used the power trio line-up, and recorded in their own right, covering Little Walter’s ‘My Babe,’ and Johnny Otis’s ‘Casting My Spell.’ Axeman Mick Green became a British Rock Legend for the powerful sound he created, with a technique often described as “playing lead and rhythm at the same time.” So Cream may have been the most powerful trio of their time, but they didn’t exactly originate the three-piece.

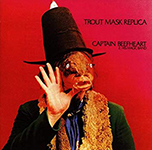

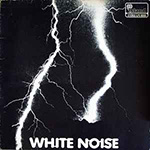

A number of reviewers have also branded the band – particularly their ‘Disraeli Gears’ album – as “psychedelic.” Now, I think I’ve taken enough mind-expanding drugs in my time to say with some sense of authority, that the Jefferson Airplane’s ‘After Bathing At Baxters’ is psychedelic; Captain Beefheart’s ‘Trout Mask Replica’ is psychedelic; White Noise’s ‘An Electric Storm’ (what do you mean you’ve never heard of it?) is psychedelic; but the most psychedelic thing about ‘Disraeli Gears’ is the cover. A veritable symphony in dayglo, it was created by Australian artist Martin Sharp, who also wrote the lyrics to “Tales of Brave Ulysses,” and it looks blinding, in every sense of the word. It’s a brilliant album, easily Cream’s best, and I’d love to review it, but there’s not enough Blues on it! There are some great, weird lyrics to some of the songs – “SWLABR” (She Was Like A Bearded Rainbow) for one – and some lovely wah-wah guitar, but it takes more than weird lyrics and wah-wah guitar to make an album, or a band, psychedelic. ‘Nuff Said!

And many people have suggested that Cream were instrumental in the birth of Heavy Metal. Well, if they were, so were their contemporaries The Jeff Beck Group and Led Zeppelin, as well as The Jimi Hendrix Experience, Free, The Who, and just about any other band of the day who used Marshall amplification. Because in those halcyon days before all amps contained a “drive” channel, and everyone had an array of foot-pedals offering a dozen different types of “overdrive,” the only way to get some “crunch” and “sustain” into your sound was to turn your amp all the way up (like Spinal Tap) plug in a high level signal producer (like a Gibson guitar with “humbucker” pickups) and literally over-drive the valves, pushing the amp past its capability to produce a clean tone.

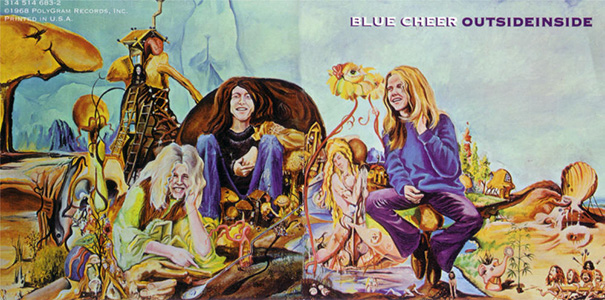

So once Jim Marshall began to produce his famous 100watt guitar amps and 4×12″ speaker cabinets, every guitarist who could afford one was plugging in and letting rip, to the annoyance of drummers everywhere. On the other side of the pond, Blue Cheer – perhaps the most powerful “power trio” of all, advertised as “the loudest band in the world,” were deafening their audiences (and allegedly themselves) with souped-up Blues and Rock’n’Roll to the delight of such luminaries as Jim Morrison of The Doors, who declared them “the single most powerful band I’ve ever seen.” And trust me, they were psychedelic! But I’m sure all devotees of true Heavy Metal will tell you, Metal’s about style, look, subject matter and attitude. Black Sabbath, Iron Maiden, Grim Reaper, Venom, Hellhammer – even the names are scary. Cream? Heavy Metal? I don’t think so. 🙂

Finally – Ginger Baker. He gets a lot of stick (well he is a drummer ha ha) for being generally arrogant and irascible, hence the title of the 2012 film “Beware Of Mr. Baker.” In his defence, he’s a very ill old man now and in a lot of physical pain, so I guess it’s not surprising if he’s grumpy, Lord knows I am. I only have one personal experience of Our Ginger, gentle reader, so let me recount it to you.

Many years ago I had a bass player in my band called John Macklin, nice guy, good player, he left me his Fender Bassman so I’m forever in his debt. Anyway, he had a personal manager (yes, really!) who rang him up one day to say Ginger Baker was down at the rehearsal studios at Chalk Farm looking for someone to jam with, and we should get our arses down there sharpish. (The question we should have asked ourselves, perhaps, was why someone as illustrious as Mr. Baker should be short of jamming partners.) Still, we turned up at the studio, talked to the guys there, set up our gear, and waited. And waited. And waited. And after a very, very long time Mr. Baker came into the room, ignored us, went through to talk to the staff, came out, ignored us again, and disappeared. Baffled, we sat there a bit longer, and finally one of the fellows came out and said, “Ginger’s done his rudiments, you might as well go home.”

I think it was probably a lucky escape, precocious young moi with my twin-necked Flying V and all, he probably would’ve eaten us alive if we’d tried to actually jam with him. 😉

©2019 Stevie King for the British Blues Archive