Resting Places

A Photographic Gallery of graveyards and gravestones of the early blues greats.

This section comprises photographs and descriptions of the resting places of early blues artists. The photographs were taken mainly by myself on various pilgrimage trips to the USA visiting the graves of many of the early blues greats.

Page being built – here is the content so far ….

|

“Mississippi” Joe Callicott (October 10, 1899 – May 1969) was an American Delta blues singer and guitarist. Callicott was born in Nesbit, Mississippi, United States. In 1929 he played second guitar in Garfield Akers’ duet recording, “Cottonfield Blues”. His “Love Me Baby Blues” has been covered by various artists, e.g. (under the title of “France Chance”) by Ry Cooder. Arhoolie Records recorded Callicott commercially in the mid-1960s. Some of his 1967 recordings (recorded by the music historian, George Mitchell) were re-released in 2003, on the Fat Possum record label. His best known recordings are “Great Long Ways From Home” and “Hoist Your Window and Let Your Curtain Down”. Callicott also recorded, as noted by one music journalist, “his lilting “Fare Thee Well Blues.”” He served as a mentor to the guitarist Kenny Brown when Brown was ten years old. Joe Callicott is buried in the Mount Olive Baptist Church Cemetery in Nesbit, Mississippi. On April 29, 1995, a memorial headstone was placed on his grave arranged by the Mt. Zion Memorial Fund with the help of Kenny Brown and financed by Chris Strachwitz, Arhoolie Records and John Fogerty. Callicott’s original marker, a simple paving stone which read simply “JOE”, was subsequently donated by his family to the Delta Blues Museum in Clarksdale, Mississippi. At the ceremony the Mount Zion Fund presented Callicott’s wife |

|

Photos coming soon … |

|

Armenter Chatmon (June 30, 1893 – September 21, 1964), known as Bo Carter, was a multi-talented blues instrumentalist and singer and a member of the family group, Mississippi Sheiks in concerts and on a few of their recordings. He also managed the group, which included his brothers Lonnie Chatmon on fiddle and, occasionally, Sam Chatmon on bass and their friend Walter Vinson on guitar and lead vocals. Since the 1960s, Bo has become best known for his bawdy songs, such as “Let Me Roll Your Lemon”, “Banana in Your Fruit Basket”, “Pin in Your Cushion”, “Your Biscuits Are Big Enough for Me”, “Please Warm My Wiener” and “My Pencil Won’t Write No More”. However, his output was not limited to ‘dirty’ blues. In 1928, he recorded the original version of “Corrine, Corrina”, which later became a hit for Big Joe Turner and has become a standard in various musical genres. Bo and his brothers (including the pianist Harry Chatmon, who also made recordings) first learned music from their father, the fiddler Henderson Chatmon, a former slave, at their home on a plantation between Bolton and Edwards, Mississippi. Their mother, Eliza, also sang and played the guitar. Bo made his recording debut in 1928, backing Alec Johnson, and was soon was recording as a solo musician. He became one of the dominant blues recording acts of the 1930s, recording 110 sides. He also played with and managed the family group, the Mississippi Sheiks, and several other acts in the area. He and the Sheiks often performed for whites, playing the pop hits of the day and white-oriented dance music, as well as for blacks, playing a bluesier repertoire. Bo went partly blind during the 1930s. He settled in Glen Allan, Mississippi, and despite his vision problems did some farming but also continued to play music and perform, sometimes with his brothers. He moved to Memphis, Tennessee, and worked outside the music industry in the 1940s. Carter suffered strokes and died of a cerebral hemorrhage at Shelby County Hospital, in Memphis, on September 21, 1964 at the age of 71. He is buried in Nitta Yuma Cemetery, Sharkey County, Mississippi. |

|

|

|

Gus Cannon Gustavus “Gus” Cannon (September 12, 1883 or 1884 – October 15, 1979) was an American blues musician who helped to popularize jug bands (such as his own Cannon’s Jug Stompers) in the 1920s and 1930s. There is uncertainty about his birth year; his tombstone gives the date as 1874. Born on a plantation in Red Banks, Mississippi, Cannon moved a hundred miles to Clarksdale, then the home of W. C. Handy, at the age of 12. His musical skills came without training; he taught himself to play a banjo that he made from a frying pan and a raccoon skin. He ran away from home at the age of fifteen and began his career entertaining at sawmills and levee and railroad camps in the Mississippi Delta around the turn of the century. While in Clarksdale, Cannon was influenced by two local musicians, Jim Turner and Alec Lee. Turner’s fiddle playing in W. C. Handy’s band so impressed Cannon that he decided to learn to play the fiddle himself. Lee, a guitarist, taught Cannon his first folk blues, “Po’ Boy, Long Ways from Home”, and showed him how to use a knife blade as a slide, a technique that Cannon adapted to his banjo playing. Cannon left Clarksdale around 1907 and soon settled near Memphis, Tennessee, where he played in a jug band led by Jim Guffin. He began playing in Memphis with Jim Jackson. He met the harmonica player Noah Lewis, who introduced him to a young guitar player, Ashley Thompson. Lewis and Thompson later were members of Cannon’s Jug Stompers. The three of them formed a band to play at parties and dances. In 1914 Cannon began touring in medicine shows. He supported his family through various jobs, including sharecropping, ditch digging, and yard work, but supplemented his income with music. Cannon began recording, as Banjo Joe, for Paramount Records in 1927. At that session he was backed by Blind Blake. After the success of the Memphis Jug Band’s first records, he quickly assembled a jug band, Cannon’s Jug Stompers, featuring Lewis and Thompson (later replaced by Elijah Avery). The group was first recorded at the Memphis Auditorium for Victor Records in January 1928. Hosea Woods joined the Jug Stompers in the late 1920s, playing guitar, banjo and kazoo and providing some vocals. Cannon’s Jug Stompers’ recording of “Big Railroad Blues” is available on the compilation album The Music Never Stopped: Roots of the Grateful Dead. Although their last recordings were made in 1930, Cannon’s Jug Stompers were one of Beale Street’s most popular jug bands through the 1930s. A few songs Cannon recorded with the Jug Stompers are “Minglewood Blues”, “Pig Ankle Strut”, “Wolf River Blues”, “Viola Lee Blues”, “White House Station” and “Walk Right In” (a pop hit for The Rooftop Singers in the 1960s and for Dr. Hook in the 1970s). By the end of the 1930s, Cannon had effectively retired, although he occasionally performed as a solo musician. Cannon made a few recordings for Folkways Records in 1956. During the blues revival of the 1960s, he made some appearances at colleges and coffee houses with Furry Lewis and Bukka White, but he had to pawn his banjo to pay his heating bill the winter before The Rooftop Singers had a hit with “Walk Right In”. In the wake of becoming a hit composer, he recorded an album for Stax Records in 1963, with fellow Memphis musicians Will Shade (the former leader of the Memphis Jug Band) on jug and Milton Roby on washboard. Cannon performed traditional songs, including “Kill It”, “Salty Dog”, “Going Around”, “The Mountain”, “Ol’ Hen”. “Gonna Raise a Ruckus Tonight”, “Ain’t Gonna Rain No More”, “Boll-Weevil”, “Come On down to My House”, “Make Me a Pallet on Your Floor”, “Get Up in the Morning Soon”, and “Crawdad Hole”, along with his own “Walk Right In”, with stories and introductions between songs. He died in Memphis, Tennessee on 15th October 1979 aged 96 (?) and is buried at Greenview Memorial Gardens, Hernando, DeSoto County, Mississippi. Note his birth date on the gravestone states 1874, the plaque states 1875 but the best estimate now is 12th September 1883. |

|

|

|

Sam Chatmon (January 10, 1897 – February 2, 1983) was a Delta blues guitarist and singer. He was a member of the Mississippi Sheiks. He may have been Charlie Patton’s half-brother. Chatmon was born in Bolton, Mississippi. His family was well known in Mississippi for their musical talents; he was a member of the family’s string band when he was young. In an interview he stated that he started playing the guitar at the age of 3, laying it flat on the floor and crawling under it. He regularly performed for white audiences in the 1900s. The Chatmon band played rags, ballads, and popular dance tunes. Two of Sam’s brothers, the fiddler Lonnie Chatmon and the guitarist Bo Carter, performed with the guitarist Walter Vinson as the Mississippi Sheiks. Chatmon played the banjo, mandolin, and harmonica in addition to the guitar. He performed at parties and on street corners throughout Mississippi for small pay and tips. In the 1930s he recorded with the Sheiks and also with his brother Lonnie as the Chatman Brothers. Chatmon moved to Hollandale, Mississippi, in the early 1940s and worked on plantations there. He was rediscovered in 1960 and started a new chapter of his career as a folk-blues artist. In the same year he recorded for Arhoolie Records. He toured extensively during the 1960s and 1970s. While in California in 1970 he made several recordings with Sue Draheim, Kenny Hall, Ed Littlefield, Lou Curtiss, Kathy Hall, Will Scarlett and others at Sweet’s Mill Music Camp, forming a group he called “The California Sheiks”. He played many of the largest and best-known folk festivals, including the Smithsonian Folklife Festival in Washington, D.C., in 1972, the Mariposa Folk Festival in Toronto in 1974, and the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival in 1976. Chatmon died on 2nd February 1983 in Hollandale, Washington County, Mississippi, aged 86, and is buried in Sanders Memorial Cemetery, Hollandale, Mississippi. A headstone memorial to Chatmon with the inscription “Sitting on top of the World” was paid for by Bonnie Raitt through the Mt. Zion Memorial Fund and placed in Sanders Memorial Cemetery, Hollandale, Mississippi, on March 14, 1998, in a ceremony held at the Hollandale Municipal Building, celebrated by the Mayor and members of the city council of Hollandale, with over 100 attendees. |

|

|

|

Clifton Chenier (June 25, 1925 – December 12, 1987), a Louisiana French-speaking native of Leonville, Louisiana, near Opelousas, was an eminent performer and recording artist of zydeco, which arose from Cajun and Creole music, with R&B, jazz, and blues influences. He played the accordion and won a Grammy Award in 1983. He was a recipient of a 1984 National Heritage Fellowship awarded by the National Endowment for the Arts, which is the United States government’s highest honor in the folk and traditional arts. He was inducted posthumously into the Blues Hall of Fame in 1989, and the Louisiana Music Hall of Fame in 2011. In 2014, he was a recipient of the Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award. He was known as the King of Zydeco, and also billed as the King of the South. |

| Photos coming soon … |

|

Robert Leroy Johnson (May 8, 1911 – August 16, 1938) was an American blues guitarist, singer, and songwriter. His landmark recordings in 1936 and 1937 display a combination of singing, guitar skills, and songwriting talent that has influenced later generations of musicians. He is now recognized as a master of the blues, particularly the Delta blues style. As an itinerant performer who played mostly on street corners, in juke joints, and at Saturday night dances, Johnson had little commercial success or public recognition in his lifetime. He participated in only two recording sessions, one in San Antonio in 1936, and one in Dallas in 1937, that produced 29 distinct songs (with 13 surviving alternate takes) recorded by famed Country Music Hall of Fame producer Don Law. These songs, recorded at low fidelity in improvised studios, were the totality of his recorded output. Most were released as 10-inch, 78 rpm singles from 1937–1938, with a few released after his death. Other than these recordings, very little was known of him during his life outside of the small musical circuit in the Mississippi Delta where he spent most of his life; much of his story has been reconstructed after his death by researchers. Johnson’s poorly documented life and death have given rise to much legend. The one most closely associated with his life is that he sold his soul to the devil at a local crossroads to achieve musical success. His music had a small, but influential, following during his life and in the two decades after his death. In late 1938 John Hammond sought him out for a concert at Carnegie Hall, From Spirituals to Swing, only to discover that Johnson had died. Brunswick Records, which owned the original recordings, was bought by Columbia Records, where Hammond was employed. Musicologist Alan Lomax went to Mississippi in 1941 to record Johnson, also not knowing of his death. Law, who by then worked for Columbia Records, assembled a collection of Johnson’s recordings titled King of the Delta Blues Singers that was released by Columbia in 1961. It is widely credited with finally bringing Johnson’s work to a wider audience. The album would become influential, especially on the nascent British blues movement; Eric Clapton has called Johnson “the most important blues singer that ever lived.” Musicians such as Bob Dylan, Keith Richards, and Robert Plant have cited both Johnson’s lyrics and musicianship as key influences on their own work. Many of Johnson’s songs have been covered over the years, becoming hits for other artists, and his guitar licks and lyrics have been borrowed by many later musicians. Renewed interest in Johnson’s work and life led to a burst of scholarship starting in the 1960s. Much of what is known about him was reconstructed by researchers such as Gayle Dean Wardlow and Bruce Conforth, especially in their 2019 award-winning biography of Johnson: Up Jumped the Devil: The Real Life of Robert Johnson (Chicago Review Press). Two films, the 1991 documentary The Search for Robert Johnson by John Hammond, Jr., and a 1997 documentary, Can’t You Hear the Wind Howl, the Life and Music of Robert Johnson, which included reconstructed scenes with Keb’ Mo’ as Johnson, were attempts to document his life, and demonstrated the difficulties arising from the scant historical record and conflicting oral accounts. Johnson was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in its first induction ceremony, in 1986, as an early influence on rock and roll. He was awarded a posthumous Grammy Award in 1991 for The Complete Recordings, a 1990 compilation album. His single “Cross Road Blues” was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame in 1998, and he was given a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award in 2006. In 2003, David Fricke ranked Johnson fifth in Rolling Stone magazine’s “100 Greatest Guitarists of All Time”. |

| Photos coming soon … |

|

David “Junior” Kimbrough (July 28, 1930 – January 17, 1998) was an American blues musician. His best-known works are “Keep Your Hands off Her” and “All Night Long”. Kimbrough was born in Hudsonville, Mississippi, and lived in the north Mississippi hill country near Holly Springs. His father, a barber, played the guitar, and Junior picked his guitar as a child. He was apparently influenced by the guitarists Lightnin’ Hopkins, Mississippi Fred McDowell and Eli Green (who had a reputation as a dangerous voodoo man). In the late 1950s Kimbrough began playing the guitar in his own style, using mid-tempo rhythms and a steady drone played with his thumb on the bass strings. This style would later be cited as a prime example of hill country blues. His music is characterized by the tricky syncopation between his droning bass strings and his midrange melodies. His soloing style has been described as modal and features languorous runs in the middle and upper registers. The result was described by music critic Robert Palmer as “hypnotic”. In solo and ensemble settings it is often polyrhythmic, which links it to the music of Africa. North Mississippi bluesman and former Kimbrough bassist Eric Deaton suggested similarities between Kimbrough’s music and that of Fulani musicians such as Ali Farka Touré. The music journalist Tony Russell wrote that “his raw, repetitive style suggests an archaic forebear of John Lee Hooker, a character his music shares with that of fellow North Mississippian R. L. Burnside”. In 1966 Kimbrough traveled to Memphis, Tennessee, to record for Goldwax Records, owned by the R&B and gospel producer Quinton Claunch. Claunch was a founder of Hi Records and is known as the man who gave James Carr and O.V. Wright their starts. Kimbrough recorded one session at American Studios. Claunch declined to release the recordings, deeming them too country. Some forty years later, Bruce Watson, of Big Legal Mess Records, approached Claunch to buy the original master tapes and the rights to release the recordings made that day. These songs were released by Big Legal Mess Records in 2009 as First Recordings. Kimbrough’s debut release was a cover version of Lowell Fulson’s “Tramp” issued as a single on the independent label Philwood in 1967. On the label of the record his name was spelled incorrectly as Junior Kimbell, and the song “Tramp” was listed as “Tram?” The B-side was “You Can’t Leave Me”. Among his other early recordings are two duets with his childhood friend Charlie Feathers in 1969. Feathers counted Kimbrough as an early influence; Kimbrough gave Feathers some of his earliest lessons on the guitar. Kimbrough recorded little in the 1970s, contributing an early version of “Meet Me in the City” to a European blues anthology. With his band, the Soul Blues Boys (then consisting of bassist George Scales and drummer Calvin Jackson), he recorded again in the 1980s for High Water, releasing a single in 1982 (“Keep Your Hands off Her” backed with “I Feel Good, Little Girl”). The label recorded a 1988 session with Kimbrough and the Soul Blues Boys (this time consisting of bassist Little Joe Ayers and drummer “Allabu Juju”), releasing it in 1997 with his 1982 single as Do the Rump! In 1987 Kimbrough made his New York debut at Lincoln Center. He received notice after live footage of him playing “All Night Long” in one of his juke joints appeared in the film documentary Deep Blues: A Musical Pilgrimage to the Crossroads, directed by Robert Mugge and narrated by Robert Palmer. This performance was recorded in 1990, in the Chewalla Rib Shack, a juke joint he opened in that year east of Holly Springs to divert crowds from his packed house parties. Beginning around 1992, Kimbrough operated Junior’s Place, a juke joint in Chulahoma, near Holly Springs, in a building previously used as a church. Kimbrough came to national attention in 1992 with his debut album, All Night Long.[8] Robert Palmer produced the album for Fat Possum, recording it in the Chulahoma joint, with Junior’s son Kent “Kinney” Kimbrough (also known as Kenny Malone) on drums and R. L. Burnside’s son Garry Burnside on bass guitar. The album featured many of his most celebrated songs, including the title track, the complexly melodic “Meet Me in the City,” and “You Better Run”, a harrowing ballad of attempted rape. All Night Long earned nearly unanimous praise from critics, receiving four stars in Rolling Stone. His joint in Chulahoma started to attract visitors from around the world, including members of U2, Keith Richards, and Iggy Pop. R. L. Burnside (who recorded for the same label) and the Burnside and Kimbrough families often collaborated on musical projects. A second album for Fat Possum, Sad Days, Lonely Nights, followed in 1994. A video for the album’s title track featured Kimbrough, Garry Burnside and Kent Kimbrough playing in Kimbrough’s juke joint. The last album he recorded, Most Things Haven’t Worked Out, was released by Fat Possum in 1997. Following his death in 1998, Fat Possum released two compilation albums of recordings Kimbrough made in the 1990s, God Knows I Tried (1998) and Meet Me in the City (1999). A greatest hits compilation, You Better Run: The Essential Junior Kimbrough, followed in 2002. Kimbrough died of a heart attack following a stroke in 1998 in Holly Springs, at the age of 67. According to Fat Possum Records, he was survived by 36 children. He is buried outside his family’s church, the Kimbrough Chapel Missionary Baptist Church, near Holly Springs. The rockabilly musician Charlie Feathers, a friend of Kimbrough’s, called him “the beginning and end of all music”; this tribute is written on Kimbrough’s tombstone. |

|

|

|

Mance Lipscomb (April 9, 1895 – January 30, 1976) was an American blues singer, guitarist and songster. He was born Beau De Glen Lipscomb near Navasota, Texas. As a youth he took the name Mance (short for emancipation) from a friend of his oldest brother, Charlie. His father was an ex-slave from Alabama; his mother was half Native American (Choctaw). Lipscomb spent most of his life working as a tenant farmer in Texas. He was discovered and recorded by Mack McCormick and Chris Strachwitz in 1960, during revival of interest in the country blues. He recorded many albums of blues, ragtime, Tin Pan Alley and folk music (most of them released by Strachwitz’s Arhoolie Records), singing and accompanying himself on acoustic guitar. Lipscomb had a “dead-thumb” finger-picking guitar technique and an expressive voice. He honed his skills by playing in nearby Brenham, Texas, with a blind musician, Sam Rogers. His first release was the album Texas Songster (1960). Lipscomb performed songs in a wide range of genres, from old songs like “Sugar Babe” (the first he ever learned) to pop numbers like “Shine On, Harvest Moon” and “It’s a Long Way to Tipperary”. In 1961 he recorded the album Trouble in Mind, released by Reprise Records. In May 1963, he appeared at the first Monterey Folk Festival, in California. Unlike many of his contemporaries, he did not record in the early blues era, but his life is well documented thanks to his autobiography, I Say Me for a Parable: The Oral Autobiography of Mance Lipscomb, Texas Bluesman, narrated to Glen Alyn (published posthumously), and also a short 1971 documentary film by Les Blank, A Well Spent Life. He began playing the guitar at an early age and played regularly for years at local gatherings, mostly what he called “Saturday night suppers” hosted by someone in the area. He and his wife regularly hosted such gatherings for a while. Most of his musical activity took place within what he called his “precinct”, the area around Navasota, until around 1960. Following his discovery by McCormick and Strachwitz, Lipscomb became an important figure in the American folk music revival of the 1960s. He was a regular performer at folk festivals and folk-blues clubs around the United States, notably the Ash Grove in Los Angeles, California. He died in Navasota in 1976 aged 80, two years after suffering a stroke. He is buried in Oakland Cemetery, Navasota, Texas. |

| Photos coming soon … |

|

Mississippi Fred McDowell Fred McDowell (January 12, 1906 – July 3, 1972), known by his stage name Mississippi Fred McDowell, was an American hill country blues singer and guitar player. McDowell was born in Rossville, Tennessee. His parents were farmers, who both died while Fred was in his youth. He took up the guitar at the age of 14 and was soon playing for tips at dances around Rossville. Seeking a change from plowing fields, he moved to Memphis in 1926, where he worked in the Buck-Eye feed mill, which processed cotton into oil and other products. In 1928, he moved to Mississippi to pick cotton. He finally settled in Como, Mississippi, in 1940 or 1941 (or maybe the late 1950s), where he worked as a full-time farmer for many years while continuing to play music on weekends at dances and picnics. After decades of playing for small local gatherings, McDowell was recorded in 1959 by roving folklore musicologist Alan Lomax and Shirley Collins on their Southern Journey field-recording trip. With interest in blues and folk music rising in the United States at the time, McDowell’s field recordings for Lomax caught the attention of blues aficionados and record producers, and within a couple of years, he had finally become a professional musician and recording artist in his own right. His LPs proved quite popular, and he performed at festivals and clubs all over the world. McDowell continued to perform blues in the north Mississippi style much as he had for decades, sometimes on electric guitar rather than acoustic guitar. He was particularly renowned for his mastery of slide guitar, a style he said he first learned using a pocketknife for a slide and later a polished beef rib bone. He ultimately settled on the clearer sound he got from a glass slide, which he wore on his ring finger. While he famously declared, “I do not play no rock and roll,” he was not averse to associating with younger rock musicians. He coached Bonnie Raitt on slide guitar technique and was reportedly flattered by The Rolling Stones’ rather straightforward version of his “You Gotta Move” on their 1971 album Sticky Fingers.[citation needed] In 1965 he toured Europe with the American Folk Blues Festival, together with Big Mama Thornton, John Lee Hooker, Buddy Guy, Roosevelt Sykes and others. McDowell’s 1969 album I Do Not Play No Rock ‘n’ Roll, recorded in Jackson, Mississippi, and released by Malaco Records, was his first featuring electric guitar. It contains parts of an interview in which he discusses the origins of the blues and the nature of love. His live album Live at the Mayfair Hotel (1995) was from a concert he gave in 1969. Tracks included versions of Bukka White’s “Shake ‘Em On Down,” Willie Dixon’s “My Babe,” Mance Lipscomb’s “Evil Hearted Woman,” plus McDowell’s self-penned “Kokomo Blues.” AllMusic noted that the album “may be the best single CD in McDowell’s output, and certainly his best concert release”. McDowell’s final album, Live in New York (Oblivion Records), was a concert performance from November 1971 at the Village Gaslight (also known as The Gaslight Cafe), in Greenwich Village, New York. McDowell died of cancer in 1972, aged 66, and was buried at Hammond Hill Baptist Church, between Como and Senatobia, Mississippi. On August 6, 1993, a memorial was placed on his grave by the Mount Zion Memorial Fund. The ceremony was presided over by the blues promoter Dick Waterman, and the memorial with McDowell’s portrait on it was paid for by Bonnie Raitt. The memorial stone was a replacement for an inaccurate (McDowell’s name was misspelled) and damaged marker. The original stone was subsequently donated by McDowell’s family to the Delta Blues Museum, in Clarksdale, Mississippi. McDowell was a Freemason and was associated with Prince Hall Freemasonry; he was buried in Masonic regalia. |

|

|

|

Blind Willie McTell (born William Samuel McTier; May 5, 1898 – August 19, 1959) was a Piedmont blues and ragtime singer and guitarist. He played with a fluid, syncopated fingerstyle guitar technique, common among many exponents of Piedmont blues. Unlike his contemporaries, he came to use twelve-string guitars exclusively. McTell was also an adept slide guitarist, unusual among ragtime bluesmen. His vocal style, a smooth and often laid-back tenor, differed greatly from many of the harsher voices of Delta bluesmen such as Charley Patton. McTell performed in various musical styles, including blues, ragtime, religious music and hokum. McTell was born in Thomson, Georgia. He learned to play the guitar in his early teens. He soon became a street performer in several Georgia cities, including Atlanta and Augusta, and first recorded in 1927 for Victor Records. He never produced a major hit record, but he had a prolific recording career with different labels and under different names in the 1920s and 1930s. In 1940, he was recorded by the folklorist John A. Lomax and Ruby Terrill Lomax for the folk song archive of the Library of Congress. He was active in the 1940s and 1950s, playing on the streets of Atlanta, often with his longtime associate Curley Weaver. Twice more he recorded professionally. His last recordings originated during an impromptu session recorded by an Atlanta record store owner in 1956. McTell died three years later, having suffered for years from diabetes and alcoholism. Despite his lack of commercial success, he was one of the few blues musicians of his generation who continued to actively play and record during the 1940s and 1950s. He did not live to see the American folk music revival, in which many other bluesmen were “rediscovered”. McTell’s influence extended over a wide variety of artists, including the Allman Brothers Band, who covered his “Statesboro Blues”, and Bob Dylan, who paid tribute to him in his 1983 song “Blind Willie McTell”, the refrain of which is “And I know no one can sing the blues like Blind Willie McTell”. Other artists influenced by McTell include Taj Mahal, Alvin Youngblood Hart, Ralph McTell, Chris Smither, Jack White, and the White Stripes. He was born William Samuel McTier in Thomson, Georgia. Most sources give the date of his birth as 1898, but researchers Bob Eagle and Eric LeBlanc suggest 1903, on the basis of his entry in the 1910 census. McTell was born blind in one eye and lost his remaining vision by late childhood. He attended schools for the blind in Georgia, New York and Michigan and showed proficiency in music from an early age, first playing the harmonica and accordion, learning to read and write music in Braille, and turning to the six-string guitar in his early teens. His family background was rich in music; both of his parents and an uncle played the guitar. He was related to the bluesman and gospel pioneer Thomas A. Dorsey. McTell’s father left the family when Willie was young. After his mother died, in the 1920s, he left his hometown and became an itinerant musician, or “songster”. He began his recording career in 1927 for Victor Records in Atlanta. McTell married Ruth Kate Williams, now better known as Kate McTell, in 1934. She accompanied him on stage and on several recordings before becoming a nurse in 1939. For most of their marriage, from 1942 until his death, they lived apart, she in Fort Gordon, near Augusta, and he working around Atlanta. In the years before World War II, McTell traveled and performed widely, recording for several labels under different names: Blind Willie McTell (for Victor and Decca), Blind Sammie (for Columbia), Georgia Bill (for Okeh), Hot Shot Willie (for Victor), Blind Willie (for Vocalion and Bluebird), Barrelhouse Sammie (for Atlantic), and Pig & Whistle Red (for Regal). The appellation “Pig & Whistle” was a reference to a chain of barbecue restaurants in Atlanta; McTell often played for tips in the parking lot of a Pig ‘n Whistle restaurant. He also played behind a nearby building that later became Ray Lee’s Blue Lantern Lounge. Like Lead Belly, another songster who began his career as a street artist, McTell favored the somewhat unwieldy and unusual twelve-string guitar, whose greater volume made it suitable for outdoor playing. In 1940 John A. Lomax and his wife, Ruby Terrill Lomax, a professor of classics at the University of Texas at Austin, interviewed and recorded McTell for the Archive of American Folk Song of the Library of Congress in a two-hour session held in their hotel room in Atlanta. These recordings document McTell’s distinctive musical style, which bridges the gap between the raw country blues of the early part of the 20th century and the more conventionally melodious, ragtime-influenced East Coast Piedmont blues sound. The Lomaxes also elicited from the singer traditional songs (such as “The Boll Weevil” and “John Henry”) and spirituals (such as “Amazing Grace”), which were not part of his usual commercial repertoire. In the interview, John A. Lomax is heard asking if McTell knows any “complaining” songs (an earlier term for protest songs), to which the singer replies somewhat uncomfortably and evasively that he does not. The Library of Congress paid McTell $10, the equivalent of $154.56 in 2011, for this two-hour session. The material from this 1940 session was issued in 1960 as an LP and later as a CD, under the somewhat misleading title The Complete Library of Congress Recordings, notwithstanding the fact that it was truncated, in that it omitted some of John A. Lomax’s interactions with the singer and entirely omitted the contributions of Ruby Terrill Lomax. McTell recorded for Atlantic Records and Regal Records in 1949, but these recordings met with less commercial success than his previous works. He continued to perform around Atlanta, but his career was cut short by ill health, mostly due to diabetes and alcoholism. In 1956, an Atlanta record store manager, Edward Rhodes, discovered McTell playing in the street for quarters and enticed him with a bottle of corn liquor into his store, where he captured a few final performances on a tape recorder. These recordings were released posthumously by Prestige/Bluesville Records as Last Session. Beginning in 1957, McTell was a preacher at Mt. Zion Baptist Church in Atlanta. McTell died of a stroke in Milledgeville, Georgia, in 1959. He was buried at Jones Grove Church, near Thomson, Georgia, his birthplace. A fan paid to have a gravestone erected on his resting place. The name given on his gravestone is Willie Samuel McTier. He was inducted into the Blues Foundation’s Blues Hall of Fame in 1981 and the Georgia Music Hall of Fame in 1990. One of McTell’s most famous songs, “Statesboro Blues”, was frequently performed by the Allman Brothers Band; it also contributes to Canned Heat’s “Goin’ Up the Country”. A short list of some of the artists who have performed the song includes Taj Mahal, David Bromberg, Dave Van Ronk, The Devil Makes Three and Ralph McTell, who changed his name on account of liking the song. Ry Cooder covered McTell’s “Married Man’s a Fool” on his 1973 album, Paradise and Lunch. Jack White, of the White Stripes considers McTell an influence; the White Stripes album De Stijl (2000) is dedicated to him and features a cover of his song “Southern Can Is Mine”. The White Stripes also covered McTell’s “Lord, Send Me an Angel”, releasing it as a single in 2000. In 2013, Jack White’s Third Man Records teamed up with Document Records to issue The Complete Recorded Works in Chronological Order of Charley Patton, Blind Willie McTell and the Mississippi Sheiks. Bob Dylan paid tribute to McTell on at least four occasions. In his 1965 song “Highway 61 Revisited”, the second verse begins, “Georgia Sam he had a bloody nose”, a reference to one of McTell’s many recording names. Dylan’s song “Blind Willie McTell” was recorded in 1983 and released in 1991 on The Bootleg Series Volumes 1-3. Dylan also recorded covers of McTell’s “Broke Down Engine” and “Delia” on his 1993 album, World Gone Wrong; Dylan’s song “Po’ Boy”, on the album Love and Theft (2001), contains the lyric “had to go to Florida dodging them Georgia laws”, which comes from McTell’s “Kill It Kid”. The Blind Willie McTell Blues Festival is held annually in Thomson, Georgia. |

|

|

|

Coming soon … |

|

Photos coming soon … |

|

Jack Owens (November 17, 1904–February 9, 1997) was an American Delta blues singer and guitarist, from Bentonia, Mississippi. Owens was born L. F. Nelson. His mother was Celia Owens; his father was George Nelson, who abandoned his family when Jack was 5 or 6 years old. After that time, he was raised by the Owens family with his maternal grandfather, the father of eight children, according to the 1910 census, two of whom shared the Nelson name. (This does not account for two more children born after that census.) While very young, Owens learned some chords on the guitar from his father and an uncle. He also learned to play the fife, fiddle, and piano while still a child, but his chosen instrument was the guitar. Owens did not seek to become a professional recording artist. He farmed, sold bootleg liquor, and ran a weekend juke joint in Bentonia for most of his life. His peer, Skip James, had left home and traveled until he found a talent agent and a record label to sign him, but Owens preferred to remain at home, selling liquor and performing only on his front porch. He was not recorded until the blues revival of the 1960s, having been rediscovered in 1966 by the musicologist David Evans, who was taken to meet Owens by either Skip James or Cornelius Bright. Evans noted that while James and Owens had many elements in common and a sound peculiar to that region, referred to as the Bentonia School, there were also strong differences in Owens’s delivery. James, Owens, Bukka White, and others from the area shared a particular guitar style and repertoire utilizing open D-minor tuning (DADFAD). Owens, though, experimented with several other tunings, which appear to have been his own. He played guitar and sang, utilizing the stomp of his boots for rhythm in the manner of some other players in the Mississippi Delta, such as John Lee Hooker. James used falsetto in his singing and had become accustomed to singing quietly for recording sessions, but Owens sang roughly in his usual singing voice and loud enough for people at a party to hear while dancing. Evans, excited to find a piece of history in Owens, made recordings of him singing, which were included on Owens’s first record album, Goin’ Up the Country, that same year, and on It Must Have Been the Devil (with Bud Spires) in 1970. Owens made other recordings (some by Alan Lomax) in the 1960s and 1970s. Owens travelled the music festival circuit in the United States and Europe in the last decades of his life, often accompanied on harmonica by his friend Bud Spires, until his death in 1997. He was frequently billed in the company of other noteworthy blues musicians who maintained a higher profile than he did but were longtime associates. One such performance was with Spires in an all-star tribute to Chess Records in 1994 at the Long Beach Blues Festival, along with Jeff Healey, Hubert Sumlin, Buddy Guy, the Staple Singers and Robert Cray’s band, among others, in Long Beach, California. He was a recipient of a 1993 National Heritage Fellowship awarded by the National Endowment for the Arts, which is the highest honor in the folk and traditional arts in the United States. Owens died in Yazoo City, Mississippi, in 1997, at the age of 92. He is buried at Old Liberty Mission Baptist Church, Bentonia, Mississippi. |

|

|

|

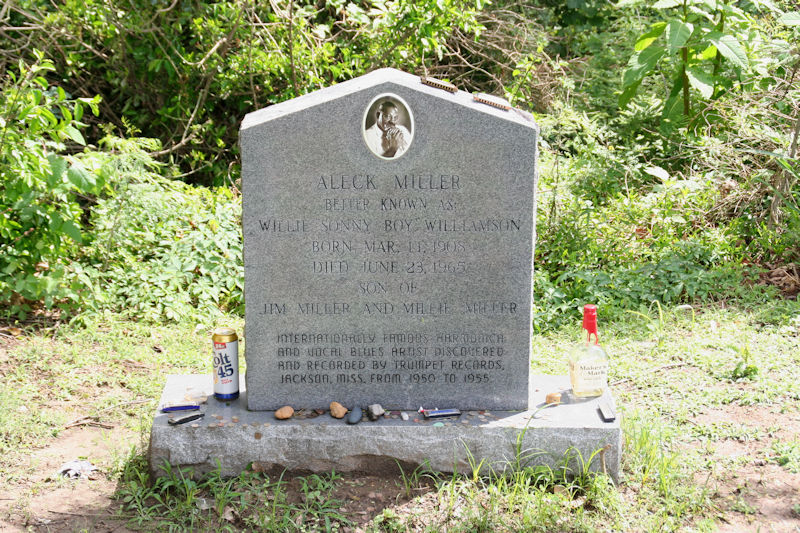

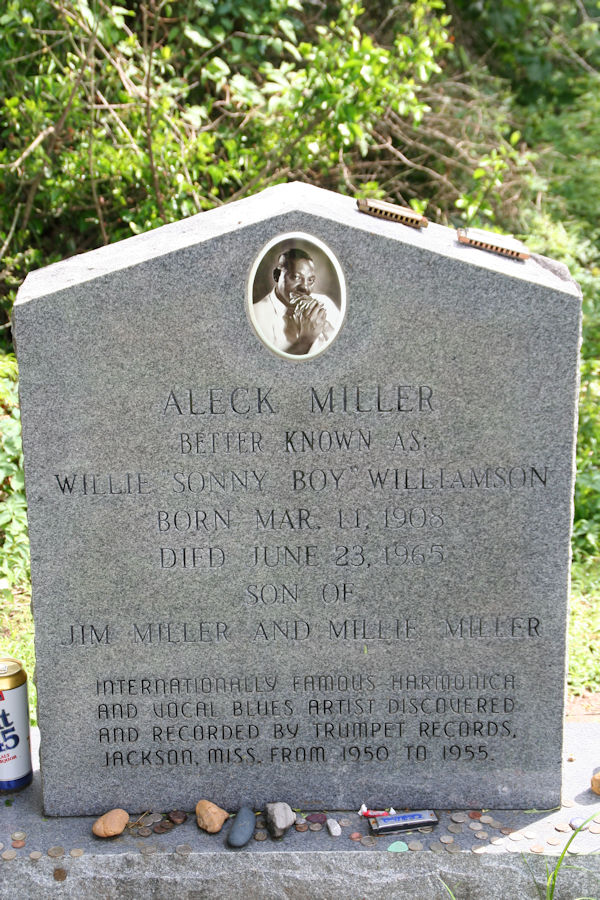

Holly Ridge, Mississippi |

|

|

|

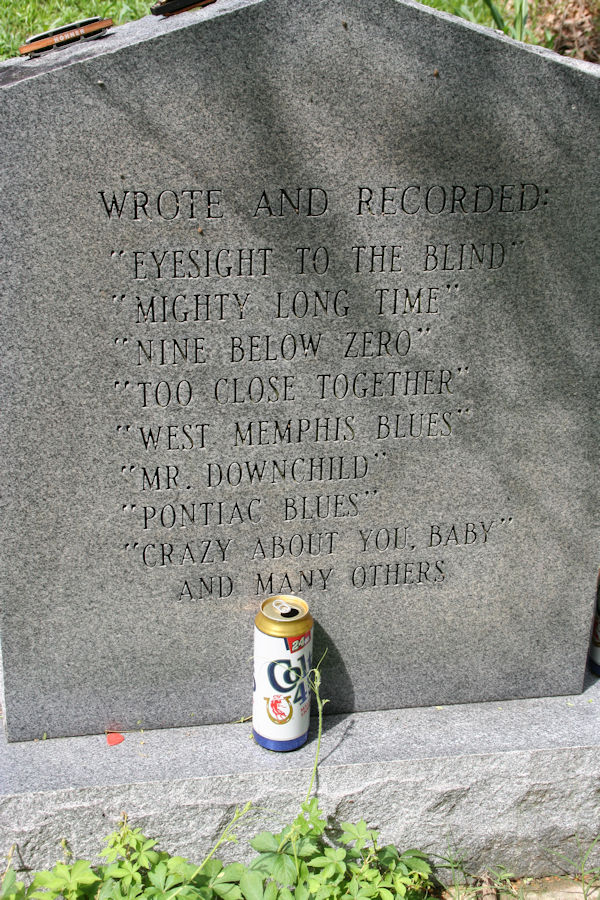

Alex or Aleck Miller (né Ford, possibly December 5, 1912 – May 24, 1965), known later in his career as Sonny Boy Williamson, was an American blues harmonica player, singer and songwriter. He was an early and influential blues harp stylist who recorded successfully in the 1950s and 1960s. Miller used various names, including Rice Miller and Little Boy Blue, before calling himself Sonny Boy Williamson, which was also the name of a popular Chicago blues singer and harmonica player. To distinguish the two, Miller has been referred to as Sonny Boy Williamson II. He first recorded with Elmore James on “Dust My Broom”. Some of his popular songs include “Don’t Start Me Talkin'”, “Help Me”, “Checkin’ Up on My Baby”, and “Bring It On Home”. He toured Europe with the American Folk Blues Festival and recorded with English rock musicians, including the Yardbirds, the Animals, and Jimmy Page. “Help Me” became a blues standard, and many blues and rock artists have recorded his songs. Miller’s date of birth is disputed. In a spoken word performance called “The Story of Sonny Boy Williamson” that was later included in several compilations, Miller states that he was born in Glendora, Mississippi in 1897. A counter claim is made that he was born Alex Ford (pronounced “Aleck”) on the Sara Jones Plantation in Tallahatchie County, Mississippi.[citation needed] Another claim is that he was born on December 5, 1899. David Evans, professor of music and an ethnomusicologist at the University of Memphis, claims to have found census records that Miller was born around 1912, being seven years old on February 2, 1920, the day of the census. However, it has been argued that a census record claim of age without a birth certificate is not a reliable proof, as census clerks often made mistakes, especially in rural towns where few people could read or write.[citation needed] Miller’s gravestone in or near Tutwiler, Mississippi, set up by record company owner Lillian McMurry twelve years after his death, gives his date of birth as March 11, 1908. He lived and worked with his sharecropper stepfather, Jim Miller, whose last name he soon adopted, and mother, Millie Ford, until the early 1930s. Beginning in the 1930s, he traveled around Mississippi and Arkansas and encountered Big Joe Williams, Elmore James and Robert Lockwood, Jr., also known as Robert Junior Lockwood, who would play guitar on his later Checker Records sides. He was also associated with Robert Johnson during this period. Miller developed his style and raffish stage persona during these years. Willie Dixon recalled seeing Lockwood and Miller playing for tips in Greenville, Mississippi, in the 1930s. He entertained audiences with novelties such as inserting one end of the harmonica into his mouth and playing with no hands. At this time he was often known as “Rice” Miller—a childhood nickname stemming from his love of rice and milk—or as “Little Boy Blue”. In 1941 Miller was hired to play the King Biscuit Time show, advertising the King Biscuit brand of baking flour on radio station KFFA in Helena, Arkansas, with Lockwood. The program’s sponsor, Max Moore, began billing Miller as Sonny Boy Williamson, apparently in an attempt to capitalize on the fame of the well-known Chicago-based harmonica player and singer Sonny Boy Williamson (birth name John Lee Curtis Williamson, died 1948). Although John Lee Williamson was a major blues star who had already released dozens of successful and widely influential records under the name “Sonny Boy Williamson” from 1937 onward, Miller would later claim to have been the first to use the name. Some blues scholars believe that Miller’s assertion he was born in 1899 was a ruse to convince audiences he was old enough to have used the name before John Lee Williamson, who was born in 1914. In 1949, Williamson relocated to West Memphis, Arkansas, and lived with his sister and her husband, Howlin’ Wolf. (Later, for Checker Records, he did a parody of Howlin’ Wolf, entitled “Like Wolf”.) He started his own KWEM radio show from 1948 to 1950, selling the elixir Hadacol. He brought his King Biscuit musician friends to West Memphis—Elmore James, Houston Stackhouse, Arthur “Big Boy” Crudup, Robert Nighthawk and others—to perform on KWEM radio. Williamson married Howlin’ Wolf’s half-sister Mae and he showed Wolf how to play harmonica. Williamson’s first recording session took place in 1951 for Lillian McMurry of Trumpet Records, based in Jackson, Mississippi. It was three years since the death of John Lee Williamson, which for the first time allowed some legitimacy to Miller’s carefully worded claim to being “the one and only Sonny Boy Williamson”. When Trumpet went bankrupt in 1955, Williamson’s recording contract was yielded to its creditors, who sold it to Chess Records in Chicago. He had begun developing a following in Chicago beginning in 1953, when he appeared there as a member of Elmore James’s band. During his Chess years he enjoyed his greatest success and acclaim, recording about 70 songs for the Chess subsidiary Checker Records from 1955 to 1964. His first LP record was a compilation of previously released singles. Titled Down and Out Blues, Checker released the collection in 1959. A single, “Boppin’ with Sonny” backed with “No Nights by Myself”, was released by Ace Records in 1955. In 1972, Chess released This Is My Story, a compilation album featuring Williamson’s recordings for the label. It was later included in Robert Christgau’s “basic record library” of 1950s and 1960s recordings, published in Christgau’s Record Guide: Rock Albums of the Seventies (1981). In the early 1960s he toured Europe several times during the height of the British blues craze, backed on a number of occasions by the Authentics (see American Folk Blues Festival), recording with the Yardbirds (for the album Sonny Boy Williamson and the Yardbirds) and the Animals, and appearing on several television broadcasts throughout Europe. Around this time he was quoted as saying of the backing bands who accompanied him, “those British boys want to play the blues real bad, and they do”. Led Zeppelin biographer Stephen Davis writes in Hammer of the Gods, while in England Williamson set his hotel room on fire while trying to cook a rabbit in a coffee percolator. The book also maintains that future Led Zeppelin vocalist Robert Plant stole one of the bluesman’s harmonicas at one of these shows. Robert Palmer wrote in his blues history “Deep Blues”, that during this tour Williamson allegedly stabbed a man during a street fight and left the country abruptly. Sonny Boy took a liking to the European fans, and while there had a custom-made, two-tone suit tailored personally for him, along with a bowler hat, matching umbrella, and an attaché case for his harmonicas. He appears credited as “Big Skol” on Roland Kirk’s live album Kirk in Copenhagen (1963). One of his final recordings from England, in 1964, featured him singing “I’m Trying to Make London My Home”, with Hubert Sumlin providing the guitar. Upon his return to the U.S., he resumed playing the King Biscuit Time show on KFFA, and performed in the Helena, Arkansas area. As fellow musicians Houston Stackhouse and Peck Curtis waited at the KFFA studios for Williamson on May 25, 1965, the 12:15 broadcast time was approaching and Williamson was nowhere in sight. Peck left the radio station to locate Williamson, and discovered his body in bed at the rooming house where he had been staying, dead of an apparent heart attack suffered in his sleep the night before. Williamson is buried on New Africa Road, just outside Tutwiler, Mississippi at the site of the former Whitman Chapel cemetery. Trumpet Records owner McMurry provided the headstone with an incorrect date of death. |

|

|

|

Photos coming soon … |

______________________________________________________________________________________________

Notes:

- Unless otherwise stated, all photographs © Copyright Alan White. All Rights Reserved.

- Additional text sources (reproduced here in context for educational use only):

www.wikipedia.org – used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Share-Alike license (CC-BY-SA);

______________________________________________________________________________________________