‘Lightnin’ Hopkins Obituary’ – by Alan Balfour, from the British Blues Archive

Note: When news reached Britain of the death of Lightnin’ Hopkins I received a call at 7pm from Phil McNeill, editor of the weekly New Musical Express, asking if I could prepare a few hundred word obituary, to be collected by courier 6am the following morning, to enable it to be published in that week’s issue. Never having produced anything without prior preparation I was not at my best. The result was that the accompanying photograph (not shown) took more space than the obituary.

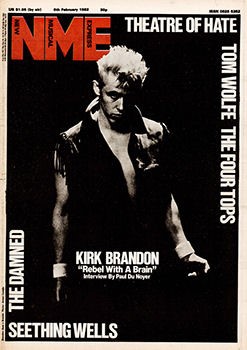

DEATH OF A LEGEND (New Musical Express w/e 6th February 1982)

LIGHTNIN’ HOPKINS, the last of the great traditional country bluesmen, died on Sunday, aged 69.

Although he had been in poor health for some time, the full extent of his condition only came to light last July. Booked to play at London’s Capital Jazz Festival, he cancelled at the last moment with a brief, poignant telegram. It read simply “Pray for Lightnin'”.

Cancer had yet again deprived us of seeing a blues artist in Britain, and now it has robbed the world of his immeasurable talent as well.

One of six children, Sam Hopkins was born in the farming community of Centerville, Texas, on March 15, 1912. He began playing the guitar as a boy on a home-made instrument fashioned out of a cigar-box and baling wire. His earliest blues influence was the legendary Blind Lemon Jefferson, of whom Hopkins recalled “When I was just a little boy I went to hanging around Buffalo, Texas Blind Lemon he’d come and I’d just get alongside and start playing.”

From Jefferson, through his cousin Texas Alexander, and via his older brother Joel, he developed his own blues style. By his early teens he had left home to sing on the streets of Houston, earning little more than dimes Throughout the ’20s and ’30s he travelled around Texas, usually in the company of recording star Texas Alexander, putting his musical abilities to good use in bars and dives. The ’40s were a lean time for Sam but as they drew to a close his reputation as a respected street singer came to the notice of the Los Angeles based Aladdin label, who signed him up in 1946.

For his first recording he was teamed with pianist Thunder Smith and together they recorded as ”Thunder and Lightnin'”, a nickname Sam was to use for the rest of his life. Over the next seven years Lightnin’ became one of the biggest recording names in Texas and certainly the most prolifically recorded bluesman of his time, cutting close on 200 sides. His status in Texas was, by today’s standards, superstar. But in 1954 he seemed to drop out of the recording limelight, not surfacing until 1959 when he was “rediscovered” by folklorists Sam Charters and Mack McCormick.

It was at this point that Lightnin’ Hopkins’s career became truly international. In the late ’50s and early ’60s the importance of the blues in the development of rock was being realised by the critics, and Hopkins (along with many other bluesmen) was finding himself in great demand the world over. Everybody from teenagers to DJs wanted to know about the blues and its practitioners, and over the next ten years Lightnin’s individualistic guitar playing, deeply emotional blues and oddball humour were to become as well known halfway around the world as they were to his neighbours in Houston, Texas.

Despite all his touring, he always seemed to find time to cut the occasional album between tours. Those “occasional albums” now almost equal the number of sides he cut when he first started out. There is currently only one UK released album available (‘Lightnin’ Strikes Back’ on Charly) but there are at least a dozen US imports on the market.

My only meeting with Hopkins was backstage at Croydon’s Fairfield Hall on his one tour of Britain in 1964. I asked him to sign an album sleeve. He looked at me over the top of his dark glasses and said rather testily (people were plaguing him like mad for interviews and discographical information) “Boy, everybody’s bin asking me one damn thing or another. I’ll sing you something from that record when I get out there. You’re here to hear me sing, ain’t ya?”

Looking back on that incident, I suppose the true legacy of Lightnin’ Hopkins is not really the albums contained in one’s collection (though that’s a good part of it) but the enrichment the music on those albums brings to life as a whole. I never did get that autograph, but Lightnin’ Hopkins has left us all a valuable legacy.

Alan Balfour