A study of the pre-war American recording industry producing recordings primarily intended for the African American market (termed “Race Records” – i.e. to refer to African Americans as a whole race of people).

____________________________________________________

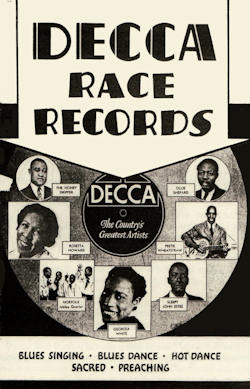

Race records were 78-rpm phonograph records marketed to African Americans between the 1920s and 1940s. They primarily contained race music, comprising various African-American musical genres, including blues, jazz, and gospel music, and also comedy. These records were, at the time, the majority of commercial recordings of African-American artists in the US. Few African-American artists were marketed to white audiences. Race records were marketed by Okeh Records, Emerson Records, Vocalion Records, Victor Talking Machine Company, Paramount Records, and several other companies.

Before the rise of the record industry in America, the cost of phonographs prevented most African Americans from listening to recorded music. At the turn of the twentieth century, the cost of listening to music went down, providing a majority of Americans with the ability to afford records. The primary purpose of records was to spur on the sale of phonographs, which were most commonly distributed in furniture stores. The stores White and Black people shopped at were separate due to segregation, so the type of music available to White and Black people varied.

Mainstream records during the 1890s and the first two decades of the 1900s were mainly made by and targeted towards White, middle class, and urban Americans. There were some exceptions, including George W. Johnson, a whistler who is widely believed to be the first Black artist ever to record commercially, in 1890. Broadway stars Bert Williams and George Walker recorded for Victor Talking Machine Company in 1901, followed by Black artists employed by other companies. Yet, the African American artists that major record companies hired before the 1920s were not properly compensated or acknowledged. This was because contracts were given to Black artists on a single record basis, so their future opportunities were not guaranteed.

African American culture greatly influenced the popular media that White Americans consumed in the 1800s. Still, there were not any primarily Black genres of music sold in early records. Perry Bradford, a famous Black composer, sparked a transition that displayed the potential for African American artists. Bradford persuaded the White executive of Okeh Records, Fred Hager, to record Mamie Smith, a Black artist who did not fit the mold of popular White music. In 1920, Smith created her ‘‘Crazy Blues/It’s Right Here for You’’ recording, which sold 75,000 copies to a majority Black audience in the first month. Okeh did not anticipate these sales and attempted to recreate their success by recruiting more Black Blues singers. Other big companies sought to profit from this new trend of race records. Columbia Records was the first to follow Okeh into the race records industry in 1921, while Paramount Records began selling race records in 1922 and Vocalion entered in the mid-1920s.

The term “race records” was first coined in 1922 by Okeh Records. Such records were labeled “race records” in reference to their marketing to African Americans, but white Americans gradually began to purchase such records as well. In the 16 October 1920 issue of the Chicago Defender, an African-American newspaper, an advertisement for Okeh records identified Mamie Smith as “Our Race Artist”. Most of the major recording companies issued “race” series of records from the mid-1920s to the 1940s.

In hindsight the term race record may seem derogatory, but in the early 20th century the African-American press routinely used the term the Race to refer to African Americans as a whole and race man or race woman to refer to an African-American individual who showed pride in and support for African-American people and culture

Marketing race records was especially important in the late 1920s, when the radio brought competition to the record industry. To maximize exposure, record labels advertised in catalogs, brochures, and newspapers popular among African Americans, like the Chicago Defender. They carefully implemented words and images that would draw in their targeted audience. Race records ads frequently reminded readers of their shared experience, claiming the music could help African Americans who moved to the North stay connected with their Southern roots.

Companies like Okeh and Paramount enforced their objectives in the 1920s by sending field scouts to Southern states to record Black artists in a one-time deal. Scouts neglected the aspirations of many singers to continue working with their companies. Field recordings were presented to the public as chance encounters to seem more genuine, yet they typically were arranged.

Perspectives on the reason White record companies invested in marketing race records vary, with some claiming it was “for the purpose of exploiting markets and expanding the capital of producers.” Advocates of this philosophy emphasize the control that the companies had on the type and form of songs that artists could create. Another perspective points to evidence such as the fact that “race records were distinguished by numerical series… in effect, segregated lists,” to support the claim that White owned companies aimed to maintain the racial divisions in society through race records. Media companies even implemented racial stereotypes in advertising to invoke Black sentiments and sell more records. Others regard the investments as being motivated simply by profit, namely by the low cost of production resulting from the easy exploitation of black writers and musicians, combined with the ease of distribution to a highly targeted class of consumers who have little access to a fully competitive marketplace.

The control of White owned music companies was tested in the 1920s, when Black Swan Records was founded in 1921 by the African American businessman Harry Pace. Black Swan was formed to integrate the Black community into a primarily White music industry, issuing around five hundred race records per year. The creation of this company brought widespread support for race records from the African American community. However some White companies in the music industry were strongly against Black Swan and threatened the company on multiple occasions.

Pace not only issued jazz, blues, and gospel records, but he put out race records that deviated from popular African American categories. These genres included classical, opera, and spirituals, chosen by Pace to encourage the advancement of African American culture. He intended the company to provide an economic ideal for African Americans to strive towards, proving that they could overcome social barriers and be successful. Hence, Black Swan paid fair wages and allowed artists to showcase their race records using their real names. Pace urged record companies owned by White individuals to recognize the demands of African Americans and increase the flow of race records in the future. Black Swan was eventually purchased by Paramount Records in 1924.

The Great Depression destroyed the race record market, leaving most African American musicians jobless. Almost every major music company removed race records from their catalogs as the country turned to the radio. Black listenership for the radio consistently stayed below ten percent of the total Black population during this time, as the music they enjoyed did not get airtime. The exclusion of Black artists on the radio was further cemented when commercial networks like NBC and CBS started to hire White singers to cover Black music. It was not until after World War II that rhythm and blues, a term spanning most sub genres of race records, gained prevalence on the radio.

It has been noted that “whole areas of black vocal tradition have been overlooked, or at best have received a few tangential references.” Though not studied comprehensively, race records have been preserved. Publications like Dixon and Godrich’s Blues and Gospel Records 1902-1943 list the names of race records that were commercially recorded and recorded in the field.

Billboard published a Race Records chart between 1945 and 1949, initially covering juke box plays and from 1948 also covering sales. This was a revised version of the Harlem Hit Parade chart, which it had introduced in 1942.

In June 1949, at the suggestion of Billboard journalist Jerry Wexler, the magazine changed the name of the chart to Rhythm & Blues Records. Wexler wrote, “‘Race’ was a common term then, a self-referral used by blacks…On the other hand, ‘Race Records’ didn’t sit well…I came up with a handle I thought suited the music well – ‘rhythm and blues.’… [It was] a label more appropriate to more enlightened times.” The chart has since undergone further name changes, becoming the Soul chart in August 1969, and the Black chart in June 1982.

Source: Wikipedia

____________________________________________________

An in-depth study of Race Records may be found in the following publications:

“Blues and Gospel Records 1890-1943”, Fourth Edition, Dixon, Godrich & Rye, Published by Oxford University Press (1997).

“Recording The Blues”, R.W.M. Dixon & J. Godrich, Published by Studio Vista Ltd (1970), Studio Vista Series editor Paul Oliver

“Race Records and The American Recording Industry (1919-1945)”, Allan Sutton, Published by Mainspring Press (2016)

____________________________________________________

Here is a summary of some of the main record labels which issued Race Records:

Ajaz

Ajax Records was a record company and label founded in 1921. Jazz and blues records were produced in New York City, with some in Montreal, and marketed via the Ajax Record Company of Chicago.

Ajax Records was a record company and label founded in 1921. Jazz and blues records were produced in New York City, with some in Montreal, and marketed via the Ajax Record Company of Chicago.

Ajax was a subsidiary of the Compo Company of Lachine, Quebec. Although a U.S. trademark on the name “Ajax” was filed in 1921, Ajax did not issue its first record until October 1923. The head of Ajax Records was H. S. Berliner, son of disc record pioneer Emile Berliner. Berliner’s corporate headquarters were in Quebec City, Quebec, although U.S. issues listed the company as being based in Chicago, Illinois, where its U.S. office was located, but apparently no recording studio. Ajax is known to have used Compo’s recording studios in Montreal and New York City. In addition to the sides which Ajax recorded themselves, the label also issued discs pressed from masters leased from New York Recording Laboratories and the Regal Record Company. The last Ajax released was in August 1925.

Ajax was marketed as “The Superior Race Record” and “The Quality Race Record.” It was sold for 75 cents. The records were pressed in Quebec but distributed in USA only, and were Compo’s only operations in the United States. Distribution of Ajax Records in the USA outside of the north-east and north-central part of the nation seems to have been poor. The records carried a catalog sequence of 17000, ending with 17136. Artists such as Rosa Henderson, Edna Hicks, Viola McCoy, Helen Gross, Monette Moore, Ethel Finnie, and Fletcher Henderson were among those who recorded for the label. Mamie Smith, who went on to record for Victor Records when Ajax folded, was signed away from Okeh Records in 1924. Joe Davis was an important talent scout for the label. Although marketed as a race records label, some mainstream material was released, including classical violin solos and pop sides by Arthur Fields and Arthur Hall and some country music.

After Ajax was discontinued in 1925, some of the masters were reissued on the American Pathé label. The audio fidelity of Ajax discs is above average for the time. Most issues are acoustic, but some late Ajax releases are electrically recorded. The historical and musical importance of the performances, and the quality of the recordings and pressings, make Ajax records highly sought-after by some record collectors.

ARC

American Record Corporation (ARC), also referred to as American Record Company, American Recording Corporation, or ARC Records, was an American record company.

American Record Corporation (ARC), also referred to as American Record Company, American Recording Corporation, or ARC Records, was an American record company.

During 1929 the American Record Corporation was established with the merger of three companies. These were the Cameo Record Corporation (which owned Cameo, Lincoln and Romeo Records), the Pathé Phonograph and Radio Corporation (which owned Actuelle, Pathé, and Perfect), and the Plaza Music Company (which owned Banner, Domino, Jewel, Oriole, and Regal).

Although Plaza’s assets were included in the merger, the Plaza company itself was not, (it formed Crown Records in 1930 as an independent label) and the Scranton Button Company, the parent company of Emerson Records (and the company that pressed records for most of these labels). Louis G. Sylvester, the former head of the Scranton Button Company, became the president of the new company, located at 1776 Broadway in Manhattan, New York City.

Consolidated Film Industries bought ARC in 1930, and Brunswick Record Corporation (actually leased Brunswick from Warner Bros) the next year. Full-priced discs were issued on Brunswick, and in 1934 on Columbia. Low-priced records on Oriole (sold at McCrory), Romeo (sold at Kress), as well as Melotone, Vocalion, Banner, and Perfect. In December 1938, the entire ARC complex was purchased for $700,000 by the Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS). The record company was renamed Columbia Recording Corporation, which revived the Columbia imprint as its flagship label with Okeh Records as a subsidiary label. This allowed the rights to the Brunswick and Vocalion labels (and pre-December 1931 Brunswick/Vocalion masters) to revert to Warner Bros., who sold the labels to Decca Records in 1941.

During August 1978 ARC was reactivated by Columbia as Maurice White’s vanity label. Acts such as Earth, Wind & Fire, Weather Report, Deniece Williams, Pockets and The Emotions were signed upon the label.

The ARC legacy is now part of Sony Music Entertainment.

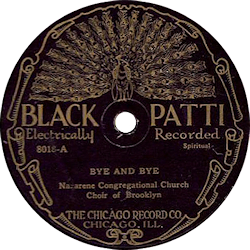

Black Patti

Black Patti Records was a short-lived record label in Chicago founded by Mayo Williams in 1927. It was named after the black opera singer Matilda Sissieretta Joyner Jones, who was called Black Patti because some thought she resembled the Italian opera singer Adelina Patti. The label lasted seven months and produced 55 records. The Black Patti peacock logo was used in the 1960s by Nick Perls for his Belzona and Yazoo labels.

Black Patti Records was a short-lived record label in Chicago founded by Mayo Williams in 1927. It was named after the black opera singer Matilda Sissieretta Joyner Jones, who was called Black Patti because some thought she resembled the Italian opera singer Adelina Patti. The label lasted seven months and produced 55 records. The Black Patti peacock logo was used in the 1960s by Nick Perls for his Belzona and Yazoo labels.

At Paramount, Mayo Williams was a successful producer of race records. When he left Paramount to start Black Patti, he had no equipment, only his Chicago office. The records were pressed at Gennett Records in Richmond, Indiana. The catalog included jazz, blues, sermons, spirituals, and vaudeville skits, most but not all by black entertainers. Willie Hightower was among the musicians who recorded for the label. Williams closed the label before the end of 1927.

Black Swan

Black Swan Records was an American jazz and blues record label founded in 1921 in Harlem, New York. It was the first widely distributed label to be owned, operated, and marketed to African Americans. (Broome Special Phonograph Records was the first to be owned and operated by African Americans). Black Swan was revived in the 1990s for CD reissues of historic jazz and blues recordings.

Black Swan Records was an American jazz and blues record label founded in 1921 in Harlem, New York. It was the first widely distributed label to be owned, operated, and marketed to African Americans. (Broome Special Phonograph Records was the first to be owned and operated by African Americans). Black Swan was revived in the 1990s for CD reissues of historic jazz and blues recordings.

Black Swan’s parent company, Pace Phonograph Corporation, was founded in March 1921 by Harry Pace and was based in Harlem. The new production company was formed after Pace’s music publishing partnership with W. C. Handy, Pace & Handy, had dissolved.

Bert Williams was an early investor in Pace Phonograph. Williams also promised to record for the company once his exclusive contract with Columbia Records ended, but he died before that could occur.

Pace Phonograph Corporation was renamed Black Swan Phonograph Company in the fall of 1922. Both the record label and production company were named after 19th century opera star Elizabeth Greenfield, who was known as the Black Swan.

Former employees of Pace & Handy staffed the new company: Fletcher Henderson, the recording manager, provided piano accompaniment for singers and led a small band for recording sessions. William Grant Still was named arranger and later musical director.[3] Noted author, activist, and academic W. E. B. Du Bois was a stockholder and member of the Board of Directors of Black Swan. Ads for Black Swan often ran in The Crisis, the magazine of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, which Du Bois edited.

Black Swan proved moderately successful. It recorded African American musicians, but as the label grew in popularity, Pace believed competing white-owned labels such as Columbia Records sought to “obstruct the progress and curtail the popularity of Black Swan Records”. Although advertising for Black Swan Records claimed all its musicians and employees were African American, it sometimes used white musicians to back some of its singers.

The production company declared bankruptcy in December 1923, and in March 1924 Paramount Records bought the Black Swan label. The Chicago Defender reported the event by noting important accomplishments of Black Swan in a short career span, including: pointed out—to the major, all white-owned, record companies—the significant market demand for black artists; prompted several major companies to begin publishing music by these performers. In addition, the Defender credited Pace with showing the majors how to target black audiences and to advertise in black newspapers. Paramount discontinued the Black Swan label a short time later.

The Black Swan label was revived in the 1990s for a series of CD reissues of historic jazz and blues recordings originally issued on Black Swan and Paramount. These CDs were issued by George H. Buck’s Jazzology and GHB labels under the control of the George H. Buck Jr. Jazz Foundation, which gained rights to the Paramount back-catalogue but not the Paramount name. Rights to the name “Black Swan Records” were also transferred to GHB.

Bluebird

Bluebird Records is a record label best known for its low-cost releases, primarily of blues and jazz in the 1930s and 1940s. It was founded in 1932 as a lower-priced RCA Victor subsidiary label. Bluebird became known for what came to be known as the “Bluebird sound”, which influenced rhythm and blues and early rock and roll.

Bluebird Records is a record label best known for its low-cost releases, primarily of blues and jazz in the 1930s and 1940s. It was founded in 1932 as a lower-priced RCA Victor subsidiary label. Bluebird became known for what came to be known as the “Bluebird sound”, which influenced rhythm and blues and early rock and roll.

The label was begun in 1932 as a division of RCA Victor by Eli Oberstein, an executive at the company. Bluebird competed with other budget labels at the time. Records were made quickly and cheaply. The “Bluebird sound” came from the session band that was used on many recordings to save money. The band included musicians such as Big Bill Broonzy, Roosevelt Sykes, Washboard Sam, and Sonny Boy Williamson. Many blues musicians were signed to RCA Victor and Bluebird by Lester Melrose, a talent scout and producer who had a virtual monopoly on the Chicago blues market. In these years, the Bluebird label became the home of Chicago blues.

Bluebird also recorded and reissued jazz and big band music. Its roster included Ted Weems, Rudy Vallée, Joe Haymes, Artie Shaw, Glenn Miller, Shep Fields, and Earl Hines. During the World War II years, Victor reissued records by Duke Ellington, Jelly Roll Morton, and Bennie Moten. Bluebird’s roster for country music included the Monroe Brothers, the Delmore Brothers, Bradley Kincaid. It reissued many titles by Jimmie Rodgers and the Carter Family.

After World War II, the Bluebird label was retired and its previously released titles were reissued on the standard RCA Victor label. In the 1950s, RCA Victor revived Bluebird for certain jazz releases and reissues, children’s records, and the low-priced RCA Victor Bluebird Classics series. In the mid-1970s, the label was again reactivated by RCA for a series of 2-LP sets of big band and jazz reissues produced by Frank Driggs and Ethel Gabriel. Currently, the Bluebird label is used for CD reissues of certain jazz and pop titles originally issued on the RCA Victor label.

RCA Victor’s entry into the budget market was the 35¢ Timely Tunes, sold through Montgomery Ward retail stores. 40 issues appeared from April to July 1931 before the label was discontinued.

The first Bluebird records appeared in July 1932 along with identically numbered Electradisk records. Test-marketed at selected Woolworth’s stores in New York City, these 8-inch discs are so rare today that some issues may no longer exist at all. They may have sold for as little as 10¢. Bluebird records bore a black-on-medium blue label, Electradisks a blue-on-orange label.

The first Bluebird records appeared in July 1932 along with identically numbered Electradisk records. Test-marketed at selected Woolworth’s stores in New York City, these 8-inch discs are so rare today that some issues may no longer exist at all. They may have sold for as little as 10¢. Bluebird records bore a black-on-medium blue label, Electradisks a blue-on-orange label.

The 8-inch series ran from 1800 to 1809, but both labels reappeared later in 1932 as 10-inch discs: Bluebird 1820–1853, continuing to April 1933, and Electradisk 2500–2509 and 1900–2177, continuing to January 1934.

Electradisks in the 2500 block were dance-band sides recorded on two days in June 1932. These rare issues were given Victor matrix numbers, but the four-digit matrix numbers on the 78 look more like discs from Crown Records, an independent label that had its own studios, though its products were pressed by Victor. The few records in that block that have been seen resemble Crowns, leading to speculation that all were recorded at Crown. The 2500 series may also have been for sale only in New York City.

In May 1933 RCA Victor restarted Bluebird as a 35¢ (3 for $1) general-interest budget record, numbered B-5000 and up, with a new blue-on-beige label (often referred as the “Buff” Bluebird, used until 1937 in the US and 1939 in Canada). Most 1800-series material was immediately reissued on the Buff label; afterwards it ran concurrently with the Electradisk series (made for Woolworth’s).

Another short-lived concurrent label was Sunrise, which may have been made for sale by artists or “mom & pop” stores. Few discs, and essentially no information, survive. Sunrise and Electradisk were discontinued early in 1934, leaving Bluebird as RCA’s only budget priced label. RCA Victor also produced a separate Montgomery Ward label for the Ward stores (see below).

Broadway

Broadway Records was the name of an American record label in the 1920s and 1930s. Broadway’s records were first manufactured in the early 1920s by the Bridgeport Die and Machine Company of Bridgeport, Connecticut. Most of the early issues were from masters recorded by Paramount Records. Starting in 1924, masters from the Emerson and Banner appeared on Broadway.

When Bridgeport Die and Machine went bankrupt in 1925, the Broadway label was acquired by the New York Recording Laboratories (NYRL), which, despite what the name suggests, was located in Port Washington, Wisconsin. NYRL was owned by the Wisconsin Chair Company, also the parent of Paramount Records. Broadway’s discs were sold at Montgomery Ward, though it’s not known if Ward’s handled the label exclusively. (Examples bearing a Chicago drugstore imprint are known.) The majority of these 1925–1930 records were Plaza masters. Starting in 1930, Crown Records masters were used in addition to NYRL’s own L-matrix series of sides recorded in Grafton, Wisconsin. NYRL went out of business in 1932 and the Broadway label was picked up by ARC for a short-lived series.

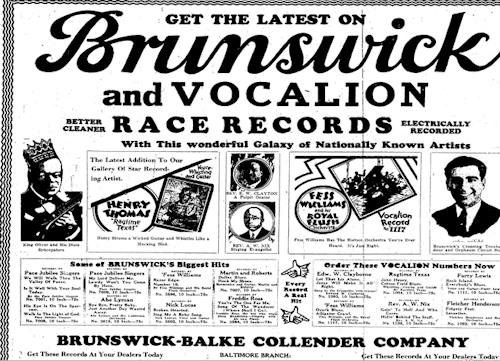

Brunswick

Brunswick Records is an American record label founded in 1916. Records under the Brunswick label were first produced by the Brunswick-Balke-Collender Company, a company based in Dubuque, Iowa which had been manufacturing products ranging from pianos to sporting equipment since 1845. The company first began producing phonographs in 1916, then began marketing their own line of records as an afterthought. These first Brunswick records used the vertical cut system like Edison Disc Records, and were not sold in large numbers. They were recorded in the United States but sold only in Canada.

Brunswick Records is an American record label founded in 1916. Records under the Brunswick label were first produced by the Brunswick-Balke-Collender Company, a company based in Dubuque, Iowa which had been manufacturing products ranging from pianos to sporting equipment since 1845. The company first began producing phonographs in 1916, then began marketing their own line of records as an afterthought. These first Brunswick records used the vertical cut system like Edison Disc Records, and were not sold in large numbers. They were recorded in the United States but sold only in Canada.

In January 1920, a new line of Brunswick Records was introduced in the U.S. and Canada that employed the lateral cut system which was becoming the default cut for 78 discs. The parent company marketed them extensively, and within a few years Brunswick became one of America’s “big three” record companies, along with Victor and Columbia Records.

The Brunswick line of home phonographs were commercially successful. Brunswick had a hit with their Ultona phonograph capable of playing Edison Disc Records, Pathé disc records, and standard lateral 78s. In late 1924, Brunswick acquired the Vocalion Records label.

Audio fidelity of early-1920s, acoustically-recorded Brunswick discs is above average for the era. They were pressed into good quality shellac, although not as durable as that used by Victor. In the spring of 1925 Brunswick introduced its own version of electrical recording (licensed from General Electric) using photoelectric cells, which Brunswick called the “light-ray process”. Only Brunswick and Vocalion records pressed at their West Coast plant bore the name “Light-Ray Process” on the labels.

Then based in Chicago (although they maintained an office and studio in New York), Brunswick initiated a 7000 race series (with the distinctive ‘lightning bolt’ label design, also used for their popular 100 hillbilly series) as well as the Vocalion 1000 race series. These race records series recorded hot jazz, urban and rural blues, and gospel.

Then based in Chicago (although they maintained an office and studio in New York), Brunswick initiated a 7000 race series (with the distinctive ‘lightning bolt’ label design, also used for their popular 100 hillbilly series) as well as the Vocalion 1000 race series. These race records series recorded hot jazz, urban and rural blues, and gospel.

In April 1930, Brunswick-Balke-Collender sold Brunswick Records to Warner Bros., and the company’s headquarters moved to New York. Warner Bros. hoped to make their own soundtrack recordings for their sound-on-disc Vitaphone system.

When Vitaphone was abandoned in favor of sound-on-film systems—and record industry sales plummeted due to the Great Depression—Warner Bros. leased the Brunswick record operation to Consolidated Film Industries, the parent company of the American Record Corporation (ARC), in December 1931. In 1932, the UK branch of Brunswick was acquired by British Decca.

Between early 1932 and 1939, Brunswick was ARC’s flagship label, selling for 75 cents, while all of the other ARC labels were selling for 35 cents. Best selling artists during that time were Bing Crosby, the Boswell Sisters, the Mills Brothers, Duke Ellington, Cab Calloway, Abe Lyman, Casa Loma Orchestra, Leo Reisman, Ben Bernie, Red Norvo, Teddy Wilson, and Anson Weeks. Many of these artists moved over to Decca in late 1934, causing Brunswick to reissue popular records by these artists on the ARC dime store labels as a means to compete with Decca’s 35 cent price.

In 1939, the American Record Corp. was bought by the Columbia Broadcasting System for $750,000, which discontinued the Brunswick label in 1940 in favor of reviving the Columbia label (as well as reviving the OKeh label replacing Vocalion). This, along with the lower than agreed-upon sales/production numbers, violated the Warner lease agreement, resulting in the Brunswick trademark reverting to Warner. In 1941, Warner sold the Brunswick and Vocalion labels to American Decca (which Warner had a financial interest in), with all masters recorded prior to December 1931. Rights to recordings from late December 1931 on were retained by CBS/Columbia.

In 1943, Decca revived the Brunswick label, mostly for reissues of recordings from earlier decades, particularly Bing Crosby’s early hits of 1931 and jazz items from the 1920s. Since then, Decca and its successors have had ownership of the historic Brunswick Records archive from this time period.

After World War II, American Decca releases were issued in the United Kingdom on the Brunswick label until 1968 when the MCA Records label was introduced in the UK. During the war, British Decca sold its American branch.

By 1952, Brunswick was put under the management of Decca’s Coral Records subsidiary. In 1957, Brunswick became a subsidiary label to Coral.

Champion

Champion

Champion Records was a record label in Richmond, Indiana, founded in 1925 by the Starr Piano Company as a division of Gennett Records, which was also in Richmond. Champion released cheaper versions of discs made by Gennett. Its issues included race records and jazz. In 1934, Champion closed and the trademark was sold to Decca Records, which brought the label back from 1935 to 1936.

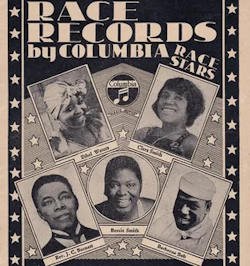

Columbia

Columbia Records is the oldest brand name in recorded sound. Founded in January 1889 in Washington DC as the Columbia Phonograph Co. by Edward D. Easton, the company first sold phonograph cylinders and later disc records.

It opened a British operation shortly afterwards. This was sold in 1922 to its own management, and then the independent Columbia Graphophone Company Ltd. itself purchased its almost bankrupt former parent in 1925. This was then merged with The Gramophone Co. Ltd., which had been set up in the UK in 1896. This company was incorporated as Electric & Musical Industries Ltd. (EMI) in 1931. US anti-trust laws forced the UK company to divest itself of its US operations that year.

[It was during this period in 1926, Columbia acquired Okeh Records and its growing stable of jazz and blues artists, including Louis Armstrong and Clarence Williams. Columbia had already built a catalog of blues and jazz artists, including Bessie Smith in their 14000-D Race series. Columbia also had a successful “Hillbilly” series (15000-D).]

[It was during this period in 1926, Columbia acquired Okeh Records and its growing stable of jazz and blues artists, including Louis Armstrong and Clarence Williams. Columbia had already built a catalog of blues and jazz artists, including Bessie Smith in their 14000-D Race series. Columbia also had a successful “Hillbilly” series (15000-D).]

The label was introduced in Japan in 1931 by the Nippon Phonograph Co. (also known as Nipponophone Co. Ltd.) which was a subsidiary of Electric & Musical Industries Ltd. In 1935 EMI sold its stake in Nipponophone, but Nipponophone kept ownership of the Columbia brand for Japan. After World War II, the label became part of Nippon Columbia Co., Ltd.

For the next few decades the Columbia imprint (trademark) was exclusively owned by Columbia Graphophone Co. Ltd., outside North America, Japan, and Spain, where the rights were owned by a company unrelated to Electric & Musical Industries Ltd., Discos Columbia, S.A. (it was eventually sold to BMG Spain through RCA). In the US and Canada, Columbia was owned by CBS Inc.

In 1965, Columbia Graphophone Company Ltd. is merged into The Gramophone Co. Ltd., with the rights to the Columbia trademark subsequently being reassigned to that company. In January 1973, The Gramophone Co. Ltd. begins phasing out some of its domestic labels (Parlophone, Regal Zonophone etc.) including Columbia, in favour of the newly established EMI label, and subsequently no longer using the label for releasing pop or rock acts in much of the world (although it remained in use in parts of Asia and for non-pop releases).

In 1965, Columbia Graphophone Company Ltd. is merged into The Gramophone Co. Ltd., with the rights to the Columbia trademark subsequently being reassigned to that company. In January 1973, The Gramophone Co. Ltd. begins phasing out some of its domestic labels (Parlophone, Regal Zonophone etc.) including Columbia, in favour of the newly established EMI label, and subsequently no longer using the label for releasing pop or rock acts in much of the world (although it remained in use in parts of Asia and for non-pop releases).

On October 15, 1990, EMI Records Ltd. (successor of The Gramophone Co. Ltd.) officially sells its international rights to the Columbia trademark to Sony Corporation. In Spain, Sony managed to acquire the rights from BMG on August 5, 2004 when Sony BMG Music Entertainment was founded. However, since the trademark was not owned by an EMI affiliate in Japan, Sony was not able to acquire it for that market. This is why Sony can’t use the Columbia brand in Japan, where the label was operated by Nippon Columbia Co., Ltd. until October 1, 2002, when the name was changed to Columbia Music Entertainment, Inc. On October 1, 2010, the name was changed back to Nippon Columbia Co., Ltd.

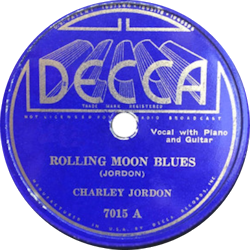

Decca

Decca

U.S. Decca was founded in 1934 by Edward R. Lewis, the head of Decca Records Ltd. of London, with Jack Kapp, Milton Rackmil and E.F. Stevens, previously three of U.S. Brunswick’s top managers, and Hermann Starr of Warner Bros. Pictures. Recording activity for Decca Records Inc. commenced in August 1934. The first blue-label American Decca records were released the following month priced at 35 cents for a 10-inch disc (55 cents for a 12-inch one).

About one month later, Decca started its 7000 “race” series targeting the Afro-American blues and rhythm and blues market. In contrast to ARC (with flagship label Brunswick), Columbia and (RCA) Victor that relegated such records to their budget-priced sub-labels (Vocalion, OKeh, Bluebird), the generally low-priced Decca was in the position to release them on their main label.

With artists like Peetie Wheatstraw, Kokomo Arnold, Blind Willie McTell, Roosevelt Sykes, Harlem Hamfats (with Joe McCoy), Sleepy John Estes, Lonnie Johnson, Louis Jordan, Big Joe Turner, Nat “King” Cole, Buddy Johnson, and the ladies Alberta Hunter, Alice Moore, Georgia White, Blue Lu Barker, and Sister Rosetta Tharpe U.S. Decca was, besides Bluebird, the most important blues and R&B label from the mid-1930s to the mid-1940s.

With artists like Peetie Wheatstraw, Kokomo Arnold, Blind Willie McTell, Roosevelt Sykes, Harlem Hamfats (with Joe McCoy), Sleepy John Estes, Lonnie Johnson, Louis Jordan, Big Joe Turner, Nat “King” Cole, Buddy Johnson, and the ladies Alberta Hunter, Alice Moore, Georgia White, Blue Lu Barker, and Sister Rosetta Tharpe U.S. Decca was, besides Bluebird, the most important blues and R&B label from the mid-1930s to the mid-1940s.

Between 1941 and 1944, the 7000 series was gradually phased out (like Decca’s main 35-cent blue-label pop series which had begun in 1934 with number 100). The last record in the 7000 series was #7910, released in July 1944.

Already in 1940, however, Decca had started a competing 8500 “Sepia” series, concentrating on R&B, which lasted to #8673 in December 1945. After that, Decca’s remains of “race” music were continued in the 48000 series for a while, then integrated in the 75-cent 23000/24000 series (black label) which was Decca’s main pop series from 1946.

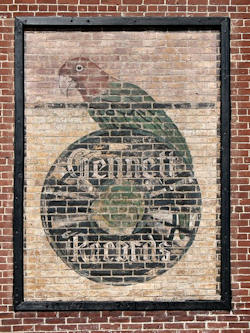

Gennett

Gennett (pronounced with a soft G) was an American record company and label in Richmond, Indiana, United States, which flourished in the 1920s. Gennett produced some of the earliest recordings of Louis Armstrong, King Oliver, Bix Beiderbecke, and Hoagy Carmichael. Its roster also included Jelly Roll Morton, Blind Lemon Jefferson, Charley Patton, and Gene Autry.

Gennett Records was founded in Richmond, Indiana, by the Starr Piano Company. It released its first records in October 1917. The company took its name from its top managers: Harry, Fred and Clarence Gennett. Earlier, the company had produced recordings under the Starr Records label. The early issues were vertically cut in the gramophone record grooves, using the hill-and-dale method of a U-shaped groove and sapphire ball stylus, but they switched to the more popular lateral cut method in April 1919.

Gennett Records was founded in Richmond, Indiana, by the Starr Piano Company. It released its first records in October 1917. The company took its name from its top managers: Harry, Fred and Clarence Gennett. Earlier, the company had produced recordings under the Starr Records label. The early issues were vertically cut in the gramophone record grooves, using the hill-and-dale method of a U-shaped groove and sapphire ball stylus, but they switched to the more popular lateral cut method in April 1919.

Gennett set up recording studios in New York City and later, in 1921, set up a second studio on the grounds of the piano factory in Richmond under the supervision of Ezra C.A. Wickemeyer.

Gennett is best remembered for the wealth of early jazz talent recorded on the label, including sessions by Jelly Roll Morton, Bix Beiderbecke, The New Orleans Rhythm Kings, King Oliver’s band with the young Louis Armstrong, Lois Deppe’s Serenaders with the young Earl Hines, Hoagy Carmichael, Duke Ellington, The Red Onion Jazz Babies, The State Street Ramblers, Zack Whyte and his Chocolate Beau Brummels, Alphonse Trent and his Orchestra and many others. Gennett also recorded early blues and gospel music artists such as Thomas A. Dorsey, Sam Collins, Jaybird Coleman, as well as early hillbilly or country music performers such as Vernon Dalhart, Bradley Kincaid, Ernest Stoneman, Fiddlin’ Doc Roberts, and Gene Autry. Many early religious recordings were made by Homer Rodeheaver, early shape note singers and others.

Gennett issued a few early electrically recorded masters recorded in the Autograph studios of Chicago in 1925. These recordings were exceptionally crude, and like many other Autograph issues are easily mistaken for acoustic masters by the casual listener. Gennett began serious electrical recording in March 1926, using a process licensed from General Electric. This process was found to be unsatisfactory, for although the quality of the recordings taken by the General Electric process was quite good, there were many customer complaints about the wear characteristics of the electric process records. The composition of the Gennett biscuit (record material) was of insufficient hardness to withstand the increased wear that resulted when the new recordings with their greatly increased frequency range were played on obsolete phonographs with mica diaphragm reproducers. The company discontinued recording by this process in August 1926, and did not return to electric recording until February 1927, after signing a new agreement to license the RCA Photophone recording process. At this time the company also introduced an improved record biscuit which was adequate to the demands imposed by the electric recording process. The improved records were identified by a newly designed black label touting the “New Electrobeam” process.

Gennett issued a few early electrically recorded masters recorded in the Autograph studios of Chicago in 1925. These recordings were exceptionally crude, and like many other Autograph issues are easily mistaken for acoustic masters by the casual listener. Gennett began serious electrical recording in March 1926, using a process licensed from General Electric. This process was found to be unsatisfactory, for although the quality of the recordings taken by the General Electric process was quite good, there were many customer complaints about the wear characteristics of the electric process records. The composition of the Gennett biscuit (record material) was of insufficient hardness to withstand the increased wear that resulted when the new recordings with their greatly increased frequency range were played on obsolete phonographs with mica diaphragm reproducers. The company discontinued recording by this process in August 1926, and did not return to electric recording until February 1927, after signing a new agreement to license the RCA Photophone recording process. At this time the company also introduced an improved record biscuit which was adequate to the demands imposed by the electric recording process. The improved records were identified by a newly designed black label touting the “New Electrobeam” process.

From 1925 to 1934, Gennett released recordings by hundreds of “old-time music” artists, precursors to country music, including such artists as Doc Roberts and Gene Autry. By the late 1920s, Gennett was pressing records for more than 25 labels worldwide, including budget disks for the Sears catalog. In 1926, Fred Gennett created Champion Records as a budget label for tunes previously released on Gennett.

The Gennett Company was hit severely by the Great Depression in 1930. It cut back on record recording and production until it was halted altogether in 1934. At this time the only product Gennett Records produced under its own name was a series of recorded sound effects for use by radio stations. In 1935 the Starr Piano Company sold some Gennett masters, and the Gennett and Champion trademarks to Decca Records. Jack Kapp of Decca was primarily interested in some jazz, blues and old time music items in the Gennett catalog which he thought would add depth to the selections offered by the newly organized Decca company. Kapp also attempted to revive the Gennett and Champion labels between 1935 and 1937 as specialists in bargain pressings of race and old-time music with but little success.

The Starr record plant soldiered on under the supervision of Harry Gennett through the remainder of the decade by offering contract pressing services. For a time the Starr Piano Company was the principal manufacturer of Decca records, but much of this business dried up after Decca purchased its own pressing plant in 1938 (the Newaygo, Michigan, plant that formerly had pressed Brunswick and Vocalion records). In the years remaining before World War II, Gennett did contract pressing for a number of New York-based jazz and folk music labels, including Joe Davis, Keynote and Asch.

With the coming of the Second World War, the War Production Board in March 1942 declared shellac a rationed commodity, limiting all record manufacturers to 70% of their 1939 shellac usage. Newly organized record labels were forced to purchase their shellac allocations from existing companies. Joe Davis purchased the Gennett shellac allocation, some of which he used for his own labels, and some of which he sold to the newly organized Capitol Records. Harry Gennett intended to use the funds from the sale of his shellac ration to modernize this pressing plant after Victory, but there is no indication that he did so, Gennett sold increasingly small numbers of special purpose records (mostly sound effects, skating rink, and church tower chimes) until 1947 or 1948, and the business then seemed to just fade away.

Brunswick Records acquired the old Gennett pressing plant for Decca. After Decca opened a new pressing plant in Pinckneyville, Illinois, in 1956, the old Gennett plant in Richmond, Indiana, was sold to Mercury Records in 1958. Mercury operated the historic plant until 1969 when it moved to a nearby modern plant later operated by Cinram. Located at 1600 Rich Road, Cinram closed the plant in 2009.

The Gennett company produced the Gennett, Starr, Champion, Superior, and Van Speaking labels, and also produced some Supertone, Silvertone, and Challenge records under contract. The firm pressed most Autograph, Rainbow, Hitch, KKK, Our Song, and Vaughn records under contract.

Herwin

Herwin Records was an American independent record label founded and run by brothers Herbert and Edwin Schiele, the trademark name being formed from their first names (HERbert and EdWIN).

Herwin Records was an American independent record label founded and run by brothers Herbert and Edwin Schiele, the trademark name being formed from their first names (HERbert and EdWIN).

Herwin Records was based in St. Louis, Missouri, and produced records starting in 1924. Most of the material released on the label was from master discs leased from Gennett Records and Paramount Records. In 1930 Herwin was sold to the Wisconsin Chair Company, the parent of Paramount Records, which discontinued the Herwin label.

In the 1960s and 1970s the Herwin label was revived by record collector Bernard Klatzko, who first used the label to issue old Library of Congress and new own recordings of rediscovered blues musicians like Bukka White, Son House and Skip James in a “78 rpm look”, from 1971 on to release vinyl record LP re-issues of historic jazz, blues and ragtime recordings.

Montgomery Ward

Montgomery Ward was a U.S. record label, 1933-1941. It was originally manufactured by the Radio-Victor Corporation of America for sale through Montgomery Ward mail-order catalogs and retail stores. The RCA-supplied pressings were high-quality products and a great bargain at 21¢ each (or 10 for $1.79). The label drew largely on a mixture of Bluebird and Victor masters, including material recorded as early as 1925, and some acoustically recorded items from the World War I era. However, Montgomery Ward’s catalog featured an extensive country music listing that included reissues of extremely rare material from Victor’s 23500 and V-40000 series.

Montgomery Ward was a U.S. record label, 1933-1941. It was originally manufactured by the Radio-Victor Corporation of America for sale through Montgomery Ward mail-order catalogs and retail stores. The RCA-supplied pressings were high-quality products and a great bargain at 21¢ each (or 10 for $1.79). The label drew largely on a mixture of Bluebird and Victor masters, including material recorded as early as 1925, and some acoustically recorded items from the World War I era. However, Montgomery Ward’s catalog featured an extensive country music listing that included reissues of extremely rare material from Victor’s 23500 and V-40000 series.

Montgomery Ward changed its supplier numerous times between 1935-1941. Production of the label shifted to Decca briefly in mid-1935. However, RCA Manufacturing Co., Inc. resumed production in early 1936 and drew on current Bluebird material. Both Decca and RCA Manufacturing Co., Inc. continued to press Montgomery Ward discs from their own masters through May, 1939, although Decca’s discs are not as well-made as are those made by RCA Manufacturing Co., Inc. In summer, 1939, Montgomery Ward contracted production to Eli Oberstein’s United States Record Corporation. These were pressed by the Scranton Button Company and contain original Varsity masters as well as dubbings from Crown, Gennett Records, and Paramount masters. Oberstein also produced a red-label Montgomery Ward record classical series that drew on material on his own Royale label. However, when United States Record Corporation declared bankruptcy in mid-1940, Montgomery Ward severed its relationship with Oberstein and returned once more to RCA Manufacturing Co., Inc. to supply its discs. The final Montgomery Ward discs include many choice race-record, country-music and ethnic material from the Bluebird catalog.

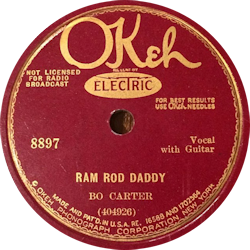

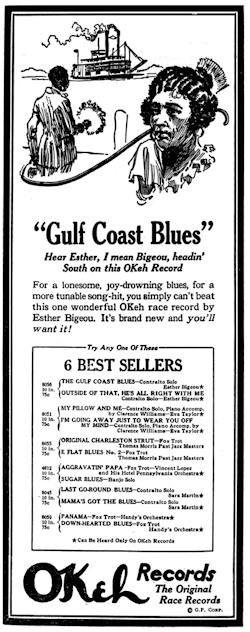

OKeh

OKeh Records is an American record label founded by the Otto Heinemann Phonograph Corporation, a phonograph supplier established in 1916, which branched out into phonograph records in 1918. The name was spelled “OKeh” from the initials of Otto K. E. Heinemann but later changed to “OKeh”. Since 1926, OKeh has been a subsidiary of Columbia Records, a subsidiary of Sony Music. OKeh is a Jazz imprint distributed by Sony Masterworks, a specialty label of Columbia.

OKeh Records is an American record label founded by the Otto Heinemann Phonograph Corporation, a phonograph supplier established in 1916, which branched out into phonograph records in 1918. The name was spelled “OKeh” from the initials of Otto K. E. Heinemann but later changed to “OKeh”. Since 1926, OKeh has been a subsidiary of Columbia Records, a subsidiary of Sony Music. OKeh is a Jazz imprint distributed by Sony Masterworks, a specialty label of Columbia.

OKeh was founded by Otto K. E. Heinemann, a German-American manager for the U.S. branch of Odeon Records, which was owned by Carl Lindstrom. In 1916, Heinemann incorporated the Otto Heinemann Phonograph Corporation, set up a recording studio and pressing plant in New York City, and started the label in 1918.

The first discs were vertical cut, but later the more common lateral-cut method was used. The label’s parent company was renamed the General Phonograph Corporation, and the name on its record labels was changed to OKeh. The common 10-inch discs retailed for 75 cents each, the 12-inch discs for $1.25. The company’s musical director was Frederick W. Hager, who was also credited under the pseudonym Milo Rega.

OKeh issued popular songs, dance numbers, and vaudeville skits similar to other labels, but Heinemann also wanted to provide music for audiences neglected by the larger record companies. OKeh produced lines of recordings in German, Czech, Polish, Swedish, and Yiddish for immigrant communities in the United States. Some were pressed from masters leased from European labels, while others were recorded by OKeh in New York.

OKeh’s early releases included music by the New Orleans Jazz Band. In 1920, Perry Bradford encouraged Fred Hager, the director of artists and repertoire (A&R), to record blues singer Mamie Smith. The records were popular, and the label issued a series of race records directed by Clarence Williams in New York City and Richard M. Jones in Chicago. From 1921 to 1932, this series included music by Williams, Lonnie Johnson, King Oliver, and Louis Armstrong. Also recording for the label were Bix Beiderbecke, Bennie Moten, Frankie Trumbauer, and Eddie Lang. As part of the Carl Lindström Company, OKeh’s recordings were distributed by other labels owned by Lindstrom, including Parlophone in the UK.

OKeh’s early releases included music by the New Orleans Jazz Band. In 1920, Perry Bradford encouraged Fred Hager, the director of artists and repertoire (A&R), to record blues singer Mamie Smith. The records were popular, and the label issued a series of race records directed by Clarence Williams in New York City and Richard M. Jones in Chicago. From 1921 to 1932, this series included music by Williams, Lonnie Johnson, King Oliver, and Louis Armstrong. Also recording for the label were Bix Beiderbecke, Bennie Moten, Frankie Trumbauer, and Eddie Lang. As part of the Carl Lindström Company, OKeh’s recordings were distributed by other labels owned by Lindstrom, including Parlophone in the UK.

In 1926, OKeh was sold to Columbia Records. Ownership changed to the American Record Corporation (ARC) in 1934, and the race records series from the 1920s ended. CBS bought the company in 1938. OKeh was a label for rhythm and blues during the 1950s, but jazz albums continued to be released, as in the work of Wild Bill Davis and Red Saunders.

General Phonograph Corporation used Mamie Smith’s popular song “Crazy Blues” to cultivate a new market. Portraits of Smith and lists of her records were printed in advertisements in newspapers such as the Chicago Defender, the Atlanta Independent, New York Colored News, and others popular with African-Americans (though Smith’s records were part of OKeh’s regular 4000 series). OKeh had further prominence in the demographic, as African-American musicians Sara Martin, Eva Taylor, Shelton Brooks, Esther Bigeou, and Handy’s Orchestra recorded for the label. OKeh issued the 8000 series for race records. The success of this series led OKeh to start recording music where it was being performed, known as remote recording or location recording. Starting in 1923, OKeh sent mobile recording equipment to tour the country and record performers not heard in New York or Chicago. Regular trips were made once or twice a year to New Orleans, Atlanta, San Antonio, St. Louis, Kansas City, and Detroit. The OKeh studio in Atlanta also catered to what was called, “Hillbilly” (now Country) stars at that time. One of the first was “Fiddlin’ John Carson, who is believed to have made the first country music recordings there in June 1923. A double sided record with “The Little Old Log Cabin in the Lane” and “The Old Hen Cackled and the Rooster’s Going To Crow.”

OKeh releases were infrequent after 1932, although the label continued into 1935. In 1940, after Columbia lost the rights to the Vocalion name by dropping the Brunswick label, the OKeh name was revived to replace it, and the script logo was introduced on a demonstration record announcing that event. The label was again discontinued in 1946 and revived again in 1951.

OKeh releases were infrequent after 1932, although the label continued into 1935. In 1940, after Columbia lost the rights to the Vocalion name by dropping the Brunswick label, the OKeh name was revived to replace it, and the script logo was introduced on a demonstration record announcing that event. The label was again discontinued in 1946 and revived again in 1951.

In 1953, OKeh became an exclusive R&B label when its parent, Columbia, transferred OKeh’s pop music artists to the newly formed Epic Records. OKeh’s music publishing division was renamed April Music.

In 1963, Carl Davis became OKeh’s A&R manager and improved OKeh’s sales for a couple of years. Epic took over management of OKeh in 1965. Among the artists during OKeh’s pop phase of the 1950s and 1960s were Johnnie Ray and Little Joe & the Thrillers.

With soul music becoming popular in the 1960s, OKeh signed Major Lance, who gave the label two big successes with “The Monkey Time” and “Um, Um, Um, Um, Um, Um”. Fifties rocker Larry Williams found a musical home for a period of time in the 1960s, recording and producing funky soul with a band that included Johnny “Guitar” Watson. He was paired with Little Richard, who had been persuaded to return to secular music. He produced two Little Richard albums for OKeh in 1966 and 1967, which returned Little Richard to the Billboard album chart for the first time in ten years and produced the hit single “Poor Dog”. He also acted as the music director for Little Richard’s live performances at the OKeh Club in Los Angeles. Bookings for Little Richard during this period skyrocketed. Williams also recorded and released material of his own and with Watson, with some moderate chart success. This period may have garnered few hits but produced some of Williams’s best and most original work.

Much of the success of OKeh in the 1960s was dependent on producer Carl Davis and songwriter Curtis Mayfield. After they left the label (due to disputes with Epic/OKeh head Len Levy), OKeh gradually slipped in sales and was quietly retired by Columbia in 1970.

In 1993, Sony Music reactivated the OKeh label (under distribution by Epic Records) as a new-age blues label. OKeh’s first new signings included G. Love & Special Sauce, Keb’ Mo, Popa Chubby, and Little Axe. Throughout the first year, in celebration of the relaunch, singles for G. Love, Popa Chubby and Keb’ Mo were released on 10-inch vinyl. By 2000, the OKeh label was again retired, and G. Love & Special Sauce was moved to Epic. It was re-launched in 2013 as a jazz line under Sony Masterworks.

In January 2013, Sony Music reactivated the OKeh label as Sony’s primary jazz imprint under Sony Masterworks. The imprint is part of Sony Masterworks in the U.S., Sony Classical’s domestic branch, focusing on both new and established artists who embody “global expressions in jazz”. The new artists include David Sanborn, Bob James, Bill Frisell, Regina Carter, and Dhafer Youssef.

Sony Music Entertainment owns the global rights to the OKeh Records catalogue through Epic Records and Sony’s Legacy Recordings reissue subsidiary. EMI’s rights to the OKeh catalogue in the UK expired in 1968, and CBS Records took over distribution.

Paramount

Paramount

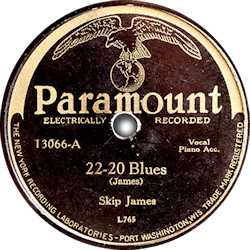

Paramount Records, a subsidiary of a chair company in Port Washington, Wisconsin, went into business in 1918 or 1919 producing rather typical dance band music. It did not earn its place in music industry legend until it started producing records for the burgeoning ‘race’ market of the 1920s. Cheaply recorded and pressed by the “The New York Recording Laboratories, Inc.”, which actually was located in Grafton, WI, this 12000/13000 series is remarkable in spite of the low audio fidelity. It includes some of the greatest blues music of the 1920s, featuring Alberta Hunter, Ida Cox, Ma Rainey, Blind Blake, Papa Charlie Jackson, Blind Lemon Jefferson, Charley Patton, Skip James, and Son House, just to name a few.

The first ‘race’ records were released probably at the end of 1922. At the beginning, catalog numbers were grouped around artists, with the emphasis on female blues vocalists, and not released chronologically. Records 12100 to 12189 are generally reissues from the Black Swan label, 12190 to 12199 were not released. Starting from 12200 at the end of 1924, record numbers were released in a rough chronological order, with exceptions notably for spirituals.

The fortunes of Paramount, “The Popular Race Record,” took a sharp downturn at the end of 1929, with the death of their most popular artist, Blind Lemon Jefferson, and the onset of the Great Depression. From then on, many issues were pressed in such small numbers that copies have not survived or remain unfound. The company struggled on until 1935, but its recording laboratory closed its doors for good in December 1933.

The fortunes of Paramount, “The Popular Race Record,” took a sharp downturn at the end of 1929, with the death of their most popular artist, Blind Lemon Jefferson, and the onset of the Great Depression. From then on, many issues were pressed in such small numbers that copies have not survived or remain unfound. The company struggled on until 1935, but its recording laboratory closed its doors for good in December 1933.

Victor

The Victor Talking Machine Company was created in the 1890s as The Consolidated Talking Machine Company by Eldridge Johnson.

Its name was changed to The Victor Talking Machine Company in 1901 following a court case victory over patents with The Columbia Gramophone Company.

For the next three decades the company was a leading American producer of phonographs and phonograph records and one of the leading phonograph companies in the world. It was headquartered in Camden, New Jersey.

In the early 1920s, Victor was slow about getting deeply involved in recording and marketing black jazz and vocal blues. By the mid-to-late 1920s, Victor had signed Jelly Roll Morton, Bennie Moten, Duke Ellington and other black bands, and was becoming very competitive with Columbia and Brunswick, even starting their own V-38000 “Hot Dance” series that was marketed to all Victor dealers. They also had a V-38500 “race” (race records) series, a 23000 ‘hot dance’ continuation of the V-38000 series, as well as a 23200 ‘Race’ series with blues, gospel and some hard jazz. However, throughout the 1930s, Victor’s involvement in jazz and blues slowed down and by the time of the musicians’ strike and the end of the war, Victor was neglecting the R&B (race) scene, which is one of the reasons so many independent companies sprang up so successfully.

In the early 1920s, Victor was slow about getting deeply involved in recording and marketing black jazz and vocal blues. By the mid-to-late 1920s, Victor had signed Jelly Roll Morton, Bennie Moten, Duke Ellington and other black bands, and was becoming very competitive with Columbia and Brunswick, even starting their own V-38000 “Hot Dance” series that was marketed to all Victor dealers. They also had a V-38500 “race” (race records) series, a 23000 ‘hot dance’ continuation of the V-38000 series, as well as a 23200 ‘Race’ series with blues, gospel and some hard jazz. However, throughout the 1930s, Victor’s involvement in jazz and blues slowed down and by the time of the musicians’ strike and the end of the war, Victor was neglecting the R&B (race) scene, which is one of the reasons so many independent companies sprang up so successfully.

In 1929 it was acquired by the Radio Corporation of America (RCA).

Vocalion

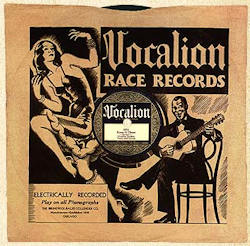

Vocalion was founded in 1916 by the Aeolian Piano Company of New York City, which introduced a retail line of phonographs at the same time. The name was derived from one of their corporate divisions, the Vocalion Organ Company. The label issued single-sided, vertical-cut disc records but switched to double-sided. In 1920 it switched to the more common lateral-cut system.

Vocalion was founded in 1916 by the Aeolian Piano Company of New York City, which introduced a retail line of phonographs at the same time. The name was derived from one of their corporate divisions, the Vocalion Organ Company. The label issued single-sided, vertical-cut disc records but switched to double-sided. In 1920 it switched to the more common lateral-cut system.

In late 1924 the label was acquired by Brunswick Records. During the 1920s Vocalion also began the 1000 race series, records recorded by and marketed to African Americans.

In April 1930, Warner Bros. bought Brunswick Records and. In December 1931 Warner Bros. licensed the entire Brunswick and Vocalion operation to the American Record Corporation. ARC used Brunswick as their flagship 75-cent label and Vocalion as one of their 35-cent labels. New signings (Dick Himber, Clarence Williams, Leroy Carr) contributed to the growing popularity of the label.

Starting in about 1935, Vocalion became even more popular with the signing of Billie Holiday, Mildred Bailey, Stuff Smith, Putney Dandridge, and Red Allen. Coupled with other short-term signings, including Fletcher Henderson, Phil Harris, Earl Hines, and Isham Jones, and their healthy Race and Country releases made Vocalion a powerhouse presence.

In 1935, Vocalion started reissuing titles that were still selling from the recently discontinued OKeh label. In 1936 and 1937 Vocalion produced the only recordings by blues guitarist Robert Johnson (as part of their ongoing field recording of blues, gospel and “out of town” jazz groups). From 1935 through 1940, Vocalion was one of the most popular labels for small-group swing, blues, and country. After the short-lived Variety label was discontinued (in late 1937), many titles were reissued on Vocalion, and the label continued to release new recordings made by Master/Variety artists through 1940. This added Cab Calloway and the Duke Ellington small groups-within-his-band (Rex Stewart, Johnny Hodges, Barney Bigard and Cootie Williams) to the label.

In 1935, Vocalion started reissuing titles that were still selling from the recently discontinued OKeh label. In 1936 and 1937 Vocalion produced the only recordings by blues guitarist Robert Johnson (as part of their ongoing field recording of blues, gospel and “out of town” jazz groups). From 1935 through 1940, Vocalion was one of the most popular labels for small-group swing, blues, and country. After the short-lived Variety label was discontinued (in late 1937), many titles were reissued on Vocalion, and the label continued to release new recordings made by Master/Variety artists through 1940. This added Cab Calloway and the Duke Ellington small groups-within-his-band (Rex Stewart, Johnny Hodges, Barney Bigard and Cootie Williams) to the label.

ARC was purchased by CBS and Vocalion became a subsidiary of Columbia Records in 1938. The popular Vocalion label was discontinued in 1940. The discontinuance of Vocalion (along with Brunswick in favor of the revived Columbia label) voided the lease arrangement Warner Bros. had made with ARC in late 1931. In a complicated move, Warner Bros. got the two labels back and promptly sold them to Decca, but CBS retained control of the post-1931 Brunswick and Vocalion masters.

The name Vocalion was resurrected in the late 1950s by Decca (US) as a budget label for back-catalog reissues. This incarnation of Vocalion ceased operations in 1973; however, its replacement as MCA’s budget imprint, Coral Records, kept many Vocalion titles in print. In 1975, MCA reissued five albums on the Vocalion label.

The name Vocalion was resurrected in the late 1950s by Decca (US) as a budget label for back-catalog reissues. This incarnation of Vocalion ceased operations in 1973; however, its replacement as MCA’s budget imprint, Coral Records, kept many Vocalion titles in print. In 1975, MCA reissued five albums on the Vocalion label.

In the UK, Decca used the Vocalion label mainly to issue US artists, replacing its Vogue label, the rights to whose name had reverted to the French Disques Vogue.

In 1997 the Vocalion brand was brought back for a new series of compact discs produced by Michael Dutton, of Dutton Laboratories, in Watford, England. This label specializes in sonic refurbishments of recordings made between the 1920s and the 1970s, often leasing master recordings made by Decca and EMI.

____________________________________________________

Record company detail sources: Wikipedia et al

____________________________________________________