Themed Photo Gallery and Information: Tupelo, Mississippi

History

Tupelo is a city in, and the county seat of, Lee County, Mississippi, United States. With an estimated population of 38,114 in 2017, Tupelo is the sixth-largest city in Mississippi and is considered a commercial, industrial, and cultural hub of North Mississippi.

Tupelo was incorporated in 1866, although the area had earlier been settled as “Gum Pond” along the Mobile and Ohio Railroad. On February 7, 1934, Tupelo became the first city to receive power from the Tennessee Valley Authority, thus giving it the nickname “The First TVA City”. Much of the city was devastated by a major tornado in 1936 that still ranks as one of the deadliest tornadoes in American history. Following electrification, Tupelo boomed as a regional manufacturing and distribution center and was once considered a hub of the American furniture manufacturing industry. Although many of Tupelo’s manufacturing industries have declined since the 1990s, the city has continued to grow due to strong healthcare, retail, and financial service industries. Tupelo is the smallest city in the United States that is the headquarters of more than one bank with over $10 billion in assets.

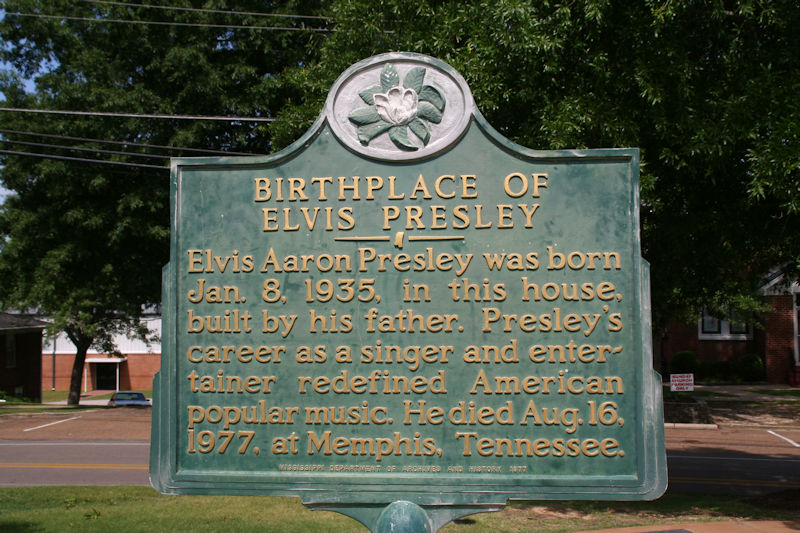

Tupelo has a deep connection to Mississippi’s music history, being known as the birthplace of Elvis Presley and Diplo as well as the origin of the group Rae Sremmurd. The city is home to multiple art and cultural institutions, including the Elvis Presley Birthplace and the 10,000-seat BancorpSouth Arena, the largest multipurpose indoor arena in Mississippi. Tupelo is the only city in the Southern United States to be named an All-America City five times, most recently in 2015. The Tupelo micropolitian area contains Lee, Itawamba, and Pontotoc counties and had a population of 140,081 in 2017.

Indigenous peoples lived in the area for thousands of years. The historic Chickasaw and Choctaw, both Muskogean-speaking peoples of the Southeast, occupied this area long before European encounter. French and British colonists traded with these indigenous peoples and tried to make alliances with them. The French established towns in Mississippi mostly on the Gulf Coast. At times, the European powers came into armed conflict. On May 26, 1736, the Battle of Ackia was fought near the site of present-day Tupelo; British and Chickasaw soldiers repelled a French and Choctaw attack on the then-Chickasaw village of Ackia. The French, under Louisiana governor Jean Baptiste Le Moyne, Sieur de Bienville, had sought to link Louisiana with Acadia and the other northern colonies of New France.

In the early 19th century, after years of trading and encroachment by European-American settlers from the United States, conflicts increased as the US settlers tried to gain land from these nations. In 1830, Congress passed the Indian Removal Act and authorized the relocation of all the Southeast Native Americans west of the Mississippi River, which was completed by the end of the 1830s.

In the early years of settlement, European-Americans named this town Gum Pond, supposedly due to its numerous tupelo trees, known locally as blackgum. The city still hosts the annual Gumtree Arts Festival.

During the Civil War, Union and Confederate forces fought in the area in 1864 in the Battle of Tupelo. Designated the Tupelo National Battlefield, the battlefield is administered by the National Park Service (NPS). In addition, the Brices Cross Roads National Battlefield, about ten miles north, commemorates another American Civil War battle. After the war, a cross-state railroad for northern Mississippi was constructed through the town, which encouraged industry and growth. With expansion, the town changed its name to Tupelo, in honor of the battle. It was incorporated in 1870.

By the early twentieth century the town had become a site of cotton textile mills, which provided new jobs for residents of the rural area. Under the state’s segregation practices, the mills employed only white adults and children. Reformers documented the child workers and attempted to protect them through labor laws.

The last known bank robbery by Machine Gun Kelly, a Prohibition-era gangster, took place on November 30, 1932 at the Citizen’s State Bank in Tupelo; his gang netted $38,000. After the robbery, the bank’s chief teller said of Kelly, “He was the kind of guy that, if you looked at him, you would never thought he was a bank robber.”

During the Great Depression, Tupelo was electrified by the new Tennessee Valley Authority, which had constructed dams and power plants throughout the region to generate hydroelectric power for the large, rural area. The distribution infrastructure was built with federal assistance as well, employing many local workers. In 1935, President Franklin Roosevelt visited this “First TVA City”.

The spring of 1936 brought Tupelo one of its worst-ever natural disasters, part of the Tupelo-Gainesville tornado outbreak of April 5–6 in that year. The storm leveled 48 city blocks and over 200 homes, killing 216 people and injuring more than 700 persons. It struck at night, destroying large residential areas on the city’s north side. Among the survivors was Elvis Presley, then a baby. Obliterating the Gum Pond neighborhood, the tornado dropped most of the victims’ bodies in the pond. The storm has since been rated F5 on the modern Fujita scale. The Tupelo Tornado is recognized as one of the deadliest in U.S. history.

The Mississippi State Geologist estimated a final death toll of 233 persons, but 100 whites were still reported as hospitalized at the time. Because the white newspapers did not publish news about blacks until the 1940s and 1950s, historians have had difficulty learning the fates of blacks injured in the tornado. Based on this, historians now estimate the death toll was higher than in official records. Fire broke out at the segregated Lee County Training School, which was destroyed. Its bricks were salvaged for other uses.

The area is subject to tornadoes. In 2008 one rated an EF3 on the Enhanced Fujita Scale struck the town. On April 28, 2014, a large tornado struck Tupelo and the surrounding communities, causing significant damage.

Historically, Tupelo served as a regional transportation hub, primarily due to its location at a railroad intersection. More recently, it has developed as strong tourism and hospitality sector based around the Elvis Presley birthplace and Natchez Trace. It is the headquarters of the historic Natchez Trace Parkway, which connects Natchez, Mississippi, to Nashville, Tennessee. The parkway follows the route of the ancient Natchez Trace trail, a path used by indigenous peoples long before the Europeans came to the area.

Source: Wikipedia

Mississippi Blues Trail Markers

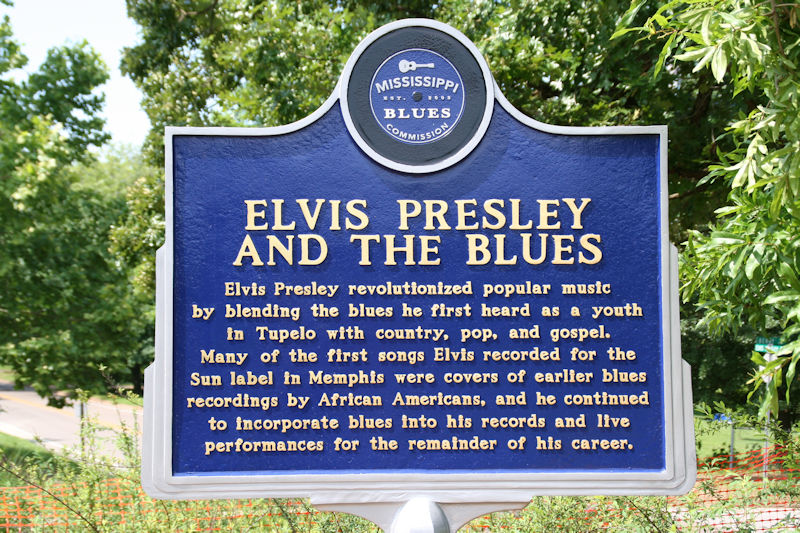

Full text:

Elvis Presley revolutionized popular music by blending the blues he first heard as a youth in Tupelo with country, pop, and gospel. Many of the first songs Elvis recorded for the Sun label in Memphis were covers of earlier blues recordings by African Americans, and he continued to incorporate blues into his records and live performances for the remainder of his career.

Elvis first encountered the blues here in Tupelo, and it remained central to his music throughout his career. The Presley family lived in several homes in Tupelo that were adjacent to African American neighborhoods, and as a youngster Elvis and his friends often heard the sounds of blues and gospel streaming out of churches, clubs, and other venues. According to Mississippi blues legend Big Joe Williams, Elvis listened in particular to Tupelo blues guitarist Lonnie Williams.

During Elvis’s teen years in Memphis he could hear blues on Beale Street, just a mile south of his family’s home. Producer Sam Phillips had captured many of the city’s new, electrified blues sounds at his Memphis Recording Service studio, where Elvis began his recording career with Phillips’s Sun label. Elvis was initially interested in recording ballads, but Phillips was more excited by the sound created by Presley and studio musicians Scotty Moore and Bill Black on July 5, 1954, when he heard them playing bluesman Arthur “Big Boy” Crudup’s 1946 recording “That’s All Right.”

That song appeared on Presley’s first single, and each of his other four singles for Sun Records also included a cover of a blues song—Arthur Gunter’s “Baby Let’s Play House,” Roy Brown’s “Good Rockin’ Tonight,” Little Junior Parker’s “Mystery Train,” and Kokomo Arnold’s “Milk Cow Blues,” recorded under the title “Milkcow Blues Boogie” by Elvis, who likely learned it from a version by western swing musician Johnnie Lee Wills. Elvis’s sound inspired countless other artists, including Tupelo rockabilly musician Jumpin’ Gene Simmons, whose 1964 hit “Haunted House” was first recorded by bluesman Johnny Fuller.

Elvis continued recording blues after his move to RCA Records in 1955, including “Hound Dog,” first recorded by Big Mama Thornton in 1952, Lowell Fulson’s “Reconsider Baby,” Big Joe Turner’s “Shake, Rattle and Roll,” and two more by Crudup, “My Baby Left Me” and “So Glad You’re Mine.” One of Elvis’s most important sources of material was the African American songwriter Otis Blackwell, who wrote the hits “All Shook Up,” “Don’t Be Cruel,” and “Return to Sender.” In Presley’s so-called “comeback” appearance on NBC television in 1968, former bandmates Scotty Moore and D. J. Fontana rejoined him as he reprised his early Sun recordings and performed other blues, including the Jimmy Reed songs “Big Boss Man” and “Baby What You Want Me to Do.” Blues remained a feature of Elvis’s live performances until his death his 1977.

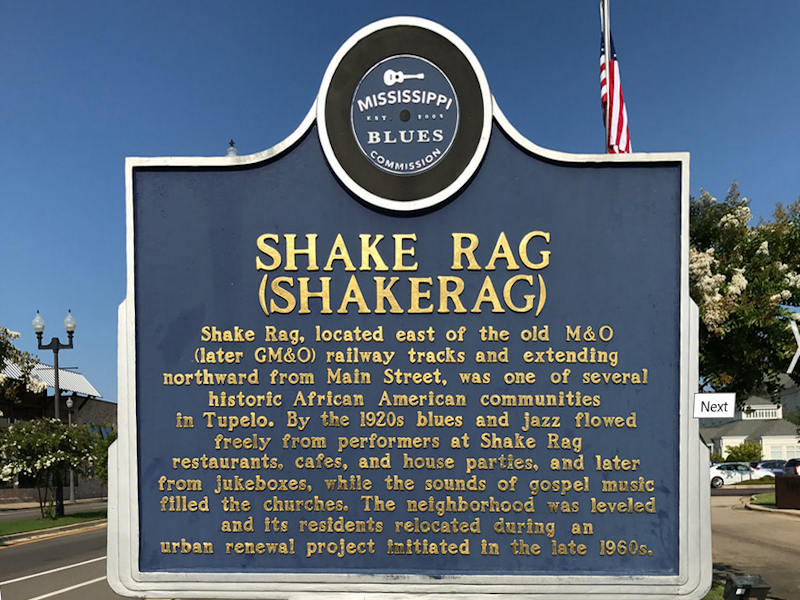

Full text:

Shake Rag, located east of the old M&O (later GM&O) railway tracks and extending northward from Main Street, was one of several historic African American communities in Tupelo. By the 1920s blues and jazz flowed freely from performers at Shake Rag restaurants, cafes, and house parties, and later from jukeboxes, while the sounds of gospel music filled the churches. The neighborhood was leveled and its residents relocated during an urban renewal project initiated in the late 1960s.

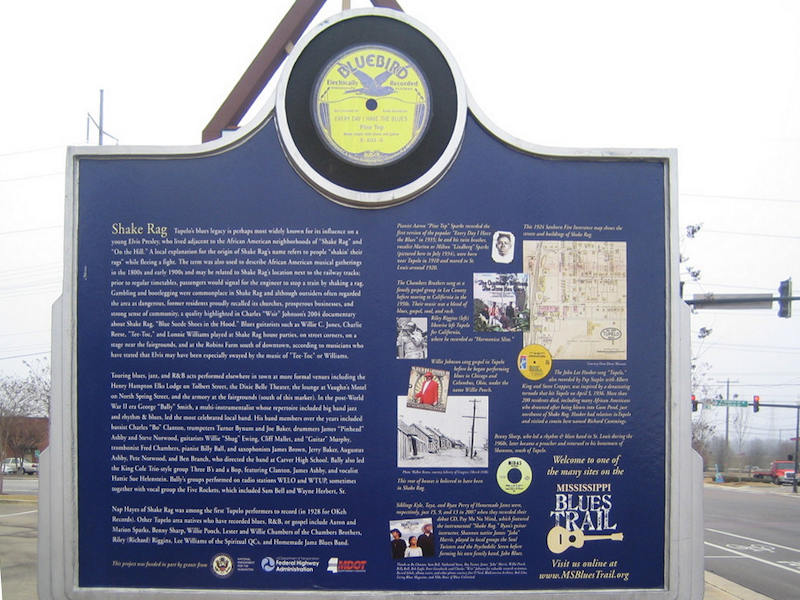

Tupelo’s blues legacy is perhaps most widely known for its influence on a young Elvis Presley, who lived adjacent to the African American neighborhoods of “Shake Rag” and “On the Hill.” A local explanation for the origin of Shake Rag’s name refers to people “shakin’ their rags” while fleeing a fight. The term was also used to describe African American musical gatherings in the 1800s and early 1900s and may be related to Shake Rag’s location next to the railway tracks; prior to regular timetables, passengers would signal for the engineer to stop a train by shaking a rag. Gambling and bootlegging were commonplace in Shake Rag and although outsiders often regarded the area as dangerous, former residents proudly recalled its churches, prosperous businesses, and strong sense of community, a quality highlighted in Charles “Wsir” Johnson’s 2004 documentary about Shake Rag, Blue Suede Shoes in the Hood. Blues guitarists such as Willie C. Jones, Charlie Reese, “Tee-Toc,” and Lonnie Williams played at Shake Rag house parties, on street corners, on a stage near the fairgrounds, and at the Robins Farm south of downtown, according to musicians who have stated that Elvis may have been especially swayed by the music of “Tee-Toc” or Williams.

Touring blues, jazz, and R&B acts performed elsewhere in town at more formal venues including the Henry Hampton Elks Lodge on Tolbert Street, the Dixie Belle Theater, the lounge at Vaughn’s Motel on North Spring Street, and the armory at the fairgrounds (south of this marker). In the post-World War II era George “Bally” Smith, a multi-instrumentalist whose repertoire included big band jazz and rhythm & blues, led the most celebrated local band. His band members over the years included bassist Charles “Bo” Clanton, trumpeters Turner Bynum and Joe Baker, drummers James “Pinhead” Ashby and Steve Norwood, guitarists Willie “Shug” Ewing, Cliff Mallet, and “Guitar” Murphy, trombonist Fred Chambers, pianist Billy Ball, and saxophonists James Brown, Jerry Baker, Augustus Ashby, Pete Norwood, and Ben Branch, who directed the band at Carver High School. Bally also led the King Cole Trio-style group Three B’s and a Bop, featuring Clanton, James Ashby, and vocalist Hattie Sue Helenstein. Bally’s groups performed on radio stations WELO and WTUP, sometimes together with vocal group the Five Rockets, which included Sam Bell and Wayne Herbert, Sr.

Nap Hayes of Shake Rag was among the first Tupelo performers to record (in 1928 for OKeh Records). Other Tupelo area natives who have recorded blues, R&B, or gospel include Aaron and Marion Sparks, Benny Sharp, Willie Pooch, Lester and Willie Chambers of the Chambers Brothers, Riley (Richard) Riggins, Lee Williams of the Spiritual QCs, and Homemade Jamz Blues Band. {See Homemade Jamz Blues Band photo below).

Source : http://msbluestrail.org/

Photo Gallery

West Main Street, Tupelo, Mississippi

Famed for the Tupelo Hardware Company store, founded by George H. Booth in 1926 and run as a family hardware store ever since. As the Tupelo community grew, so did the hardware business, evolving from an agricultural community store to a 21st century business where laser technology survey instruments are sold. It was here that Gladys Presley brought her 10 year old son Elvis to buy him his birthday present. Elvis would have preferred a rifle, but his mother succeeded in persuading him to have a guitar instead. Elvis strummed the guitar for a while whilst his mother paid $7.75 plus 2% sales tax.

Inside the store

Yes, they still sell guitars!

Homemade Jamz Blues Band

Tupelo, Mississippi based blues trio consisting of siblings Ryan (vocals an guitar), Kyle (bass) and Taya (drums). They made music history as the youngest blues band to achieve a record deal when Ryan was aged 16, Kyle was 14 and Taya was 9, with their debut album ‘Pay Me No Mind’ released in June 2008. They have since played blues festivals and gigs across North America and Europe. Aside from their youth, the band has been noted for their homemade instruments: the guitar and bass used by Ryan and Kyle are crafted from Ford motor parts that still feature the manufacturer’s logo. The photo was taken at The Chicago Blues Festival 2010.