Themed Photo Gallery and Information: Jackson, Mississippi

History – Farish Street Neighborhood Historic District

Farish Street Neighborhood Historic District is an historic neighborhood in Jackson, Mississippi, known as a hub for Black-owned businesses up until the 1970s. Named after a family that lived and had businesses on that street for four generations, the street became a flourishing business area after the imposition of legal segregation under Jim Crow. As the black community thrived, by 1908 one third of the area of Jackson was black-owned, one third of the houses where blacks lived were black-owned, and half of black families owned their own homes. In 1915 the Farish Street neighborhood was well known as a progressive area in Jackson. Farish Street was home to Trumpet Records, Ace Records, and Speir Phonograph Company. Jackson State University, a historically Black university, was located at the corner of Farish and Griffith for about a year until it moved to its new location.

The Farish Street neighborhood was added as a historic district to the National Register of Historic Places in 1980. The neighborhood is historically significant as an economically independent black community, and as of 1980 was the largest such community in Mississippi. Most of the properties in the district were built between 1890 and 1930.

Source: Wikipedia

Click here for full Wikipedia entry for Jackson MS

Mississippi Blues Trail Markers

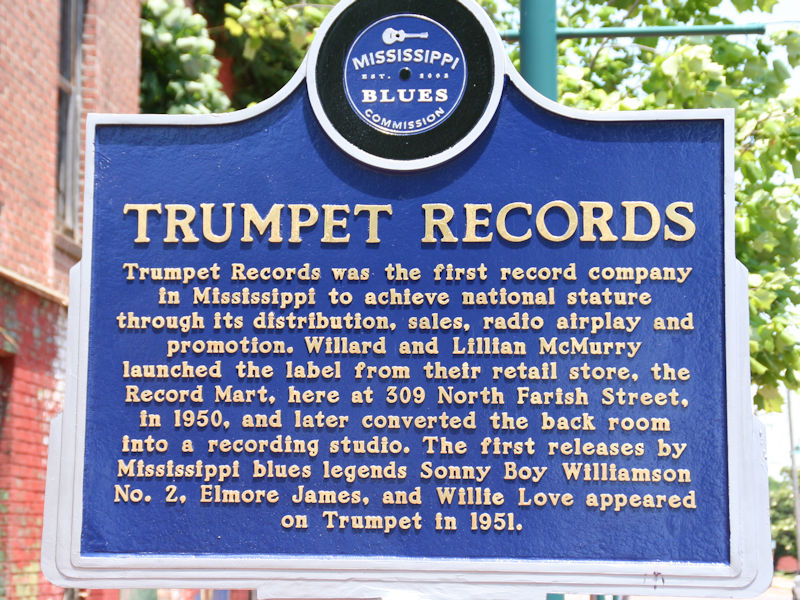

Full text:

Trumpet Records was the first record company in Mississippi to achieve national stature through its distribution, sales, radio airplay and promotion. Willard and Lillian McMurry launched the label from their retail store, the Record Mart, here at 309 North Farish Street, in 1950, and later converted the back room into a recording studio. The first releases by Mississippi blues legends Sonny Boy Williamson No. 2, Elmore James, and Willie Love appeared on Trumpet in 1951.

Willard and Lillian McMurry, who were furniture dealers by trade, entered the record business by chance, when they acquired a stock of blues and rhythm & blues 78 rpm discs with the inventory of a hardware store they purchased at this site in 1949. They turned the building into the Record Mart when they discovered they had a ready-made market for blues and gospel records on Farish Street, which was already home to much of Jackson’s African American music and commerce. The Record Mart also came to serve as the headquarters for Diamond Record Company, Trumpet Records, Globe Music, and Globe Records.

On April 3, 1950, the McMurrys brought the St. Andrews Gospelaires into a local radio station (WRBC) for Trumpet’s first recording session. During the next three years, Trumpet utilized sixteen different studios, in Jackson and other cities, before Lillian McMurry began in-house recording, first at the McMurrys’ State Furniture Company at 211 South State Street, and then at Diamond Studio in this building. The primary artist on the Trumpet label was Sonny Boy Williamson (Rice Miller), who had eleven records released between 1951 and 1955, the label’s final year of operation. The McMurrys continued to record country artists for their Globe label until 1956.

“Dust My Broom” by Elmo (Elmore) James was the only Trumpet record to reach the national rhythm & blues charts of Billboard magazine (in April 1952), but other records by Williamson and Willie Love appeared on regional charts as far away as California and Colorado. Among other artists who recorded for Trumpet were bluesmen Jerry McCain, Big Joe Williams, Tiny Kennedy, Luther Huff, Arthur Crudup, Clayton Love, Wally Mercer, and Sherman Johnson; gospel groups such as the Southern Sons Quartette and the Blue Jay Gospel Singers; and country singers, including Lucky Joe Almond and Jimmy Swan.

Lillian McMurry, the creative force behind the label, was known for her sense of fairness and her meticulous accounting. For decades after the last Trumpet record was released, she continued to administer the company’s musical rights, taking legal action when necessary to hold other companies accountable for reissues and recordings of Trumpet material, and paying royalties to the original artists, songwriters, and their heirs. Lillian McMurry was elected to the Blues Foundation’s Blues Hall of Fame in 1998. She died on March 18, 1999. Her husband Willard, who provided the backbone of support for their business ventures, died on June 7, 1996.

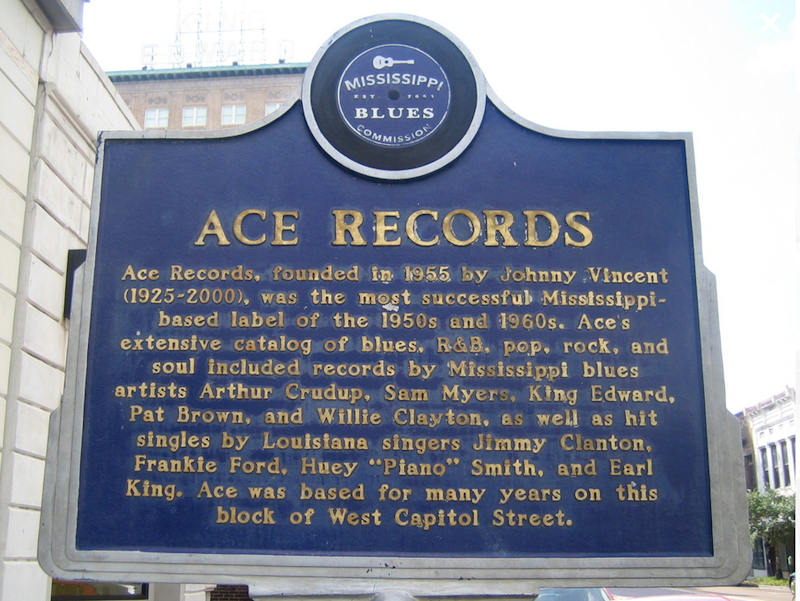

Full text:

Ace Records, founded in 1955 by Johnny Vincent (1925-2000), was the most successful Mississippi-based label of the 1950s and 1960s. Ace’s extensive catalog of blues, R&B, pop, rock, and soul included records by Mississippi blues artists Arthur Crudup, Sam Myers, King Edward, Pat Brown, and Willie Clayton, as well as hit singles by Louisiana singers Jimmy Clanton, Frankie Ford, Huey “Piano” Smith, and Earl King. Ace was based for many years on this block of West Capitol Street.

Johnny Vincent, born John Vincent Imbraguglio (later modified to Imbragulio) on October 3, 1925, became fascinated with the blues via the jukebox at his parents’ restaurant in Laurel. After serving in the Merchant Marine he started his own jukebox business in Laurel, and in 1947 became a sales representative for a New Orleans record distributor. In the late ’40s Vincent purchased Griffin Distributing Company in Jackson and operated both Griffin and a retail business, the Record Shop, at 241 North Farish Street. He started the Champion label in the early ’50s, issuing blues singles by Arthur “Big Boy” Crudup of Forest and Jackson musicians Joe Dyson and Bernard “Bunny” Williams. In 1953 Vincent signed on as a talent scout for Los Angeles-based Specialty Records. His most notable production for Specialty was “The Things I Used to Do,” recorded in New Orleans by Guitar Slim, aka Eddie Jones, a native of Greenwood. Featuring Ray Charles on piano, the song was one of the biggest R&B hits of the 1950s. During his tenure with Specialty Vincent also supervised sessions by John Lee Hooker, Kenzie Moore, and others.

In 1955 Vincent started Ace, named after the Ace Combs brand. The label’s first hit, “Those Lonely, Lonely Nights” by New Orleans bluesman Earl King, was recorded at Trumpet Records’ Diamond Recording Studio at 309 North Farish Street. Ace became the first important regional label for New Orleans music, scoring national hits by Louisiana artists Huey Smith and the Clowns (“Don’t You Just Know It”), Frankie Ford (“Sea Cruise”), and Jimmy Clanton, a “teen idol” whose “Just A Dream” topped the R&B charts in 1960. Among the Ace artists who recorded either at the New Orleans studio of Cosimo Matassa or here in Jackson in the 1950s and ‘60s were Sam Myers, Joe Tex, Bobby Marchan, James Booker, Charles Brown, Joe Dyson, Lee Dorsey, Rufus McKay, Scotty McKay, Big Boy Myles, Tim Whitsett, and Mac Rebennack, later known as “Dr. John.”

In 1962 Vincent signed a potentially lucrative distribution deal with Vee-Jay Records of Chicago, but that label’s bankruptcy in 1966 was catastrophic for Ace. In the ’70s Vincent revamped Ace, making new recordings as well as repackaging old hits, but had only limited success. He turned to various other enterprises, including a restaurant, but returned to the record business with full force in the early ’90s, as he reoriented Ace to the contemporary soul-blues market with a roster that included Mississippi-born singers Cicero Blake, Robert “The Duke” Tillman, J. T. Watkins, Pat Brown, and Willie Clayton. The latter pair had success with the duet “Equal Opportunity.” In 1997 Vincent sold Ace to the British firm Music Collection International but started a new label, Avanti, and continued to record soul-blues artists. Vincent died on February 4, 2000.

Johnny Vincent dropped his surname, Imbragulio, at the suggestion of Specialty Records owner Art Rupe, who told him “Vincent” was easier to pronounce. Vincent was known as one of the most colorful figures in the record industry. With the proceeds from his early hits on Ace Vincent was able to buy a nine-story building on Capitol Street in 1959. Another Vincent property on Northside Drive became the first offices of Jackson-based blues and soul label Malaco, whose founders Wolf Stephenson and Tommy Couch were mentored by Vincent. In the 1970s Vincent operated from other addresses on Capitol Street.

Ace and its subsidiary labels Vin and Teem released many recordings by R&B, rockabilly, and country performers, as well as down-home blues by Arthur Crudup, Frankie Lee Sims, Lightnin’ Hopkins, and Lightnin’ Slim. Ace also licensed Trumpet recordings by Sonny Boy Williamson No. 2 (Rice Miller) and Elmore James.

The 1981 album Genuine Mississippi Blues featured Jackson-based artists King Edward, Sam Myers, and Big Bad Smitty, former Jackson bluesmen Elmore James, Jr., and Johnny Littlejohn, and Como, Mississippi, guitarist Fred McDowell.

Sam Myers and John “Big Bad Smitty” Smith worked together in Jackson in the 1970s, when they both recorded tracks for the Genuine Mississippi Blues LP at the Ace studio. Myers also recorded the Ace single “Sleeping in the Ground” in 1957.

Joe Dyson, the drummer on “Those Lonely, Lonely Nights,” led the house band at Stevens Rose Room, Jackson’s finest blues nightclub in the 1950s.

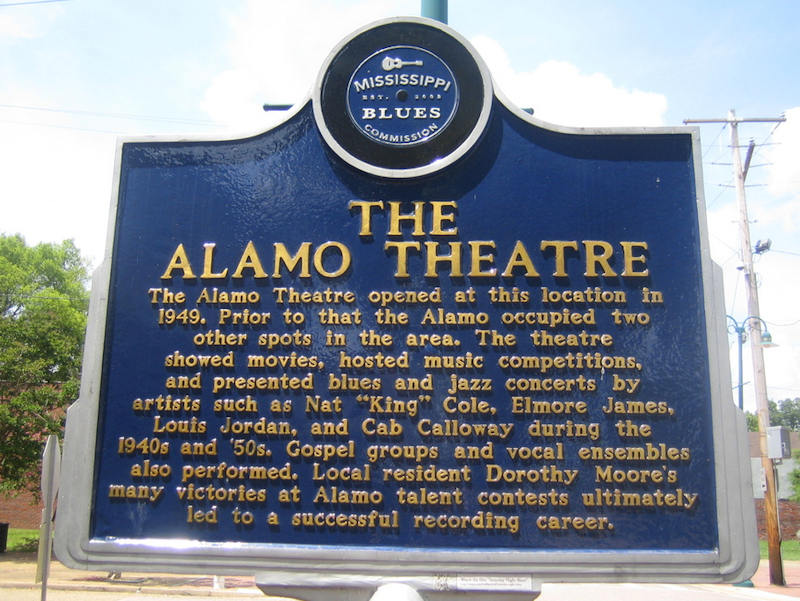

Full text:

The Alamo Theatre opened at this location in 1949. Prior to that the Alamo occupied two other spots in the area. The theatre showed movies, hosted music competitions, and presented blues and jazz concerts by artists such as Nat “King” Cole, Elmore James, Louis Jordan, and Cab Calloway during the 1940s and ‘50s. Gospel groups and vocal ensembles also performed. Local resident Dorothy Moore’s many victories at Alamo talent contests ultimately led to a successful recording career.

Talent shows have long served as an entry to the world of professional entertainment, and in Jackson many aspiring artists began their careers in contests at the Alamo Theatre. One was Dorothy Moore, who was offered a recording contract after consistently winning the Wednesday night talent contests here while in junior high. In 1966 she recorded an album as the lead singer of the vocal group the Poppies. Moore later sang background vocals for Malaco Records in Jackson and was soon recording there as a featured artist. In 1976 her record “Misty Blue” was a huge hit and established Malaco as a major player in the soul and blues field. Her other hits included “Funny How Time Slips Away,” “I Believe You,” and “With Pen In Hand.” She later formed her own label, Farish Street Records, and her honors include a 1996 Governor’s Award For Excellence in the Arts.

For many decades the Alamo served as a major African American entertainment venue under the management of Arthur Lehmann. The theatre opened at 134 North Farish Street in 1915 and moved to123 West Amite Street, just off Farish, in the 1920s. In 1948 Lehmann constructed a new building at this location to house the Alamo. Lehmann sold the property in 1957. The Alamo served mostly as a movie theatre, initially showing piano-accompanied silent movies and, after 1932, “soundies.” The theatre also booked vaudeville, jazz, blues, and gospel performers, including Elmore James, Tiny Bradshaw, Nat King Cole, and the Rays of Rhythm from Mississippi’s Piney Woods School. Al Benson, who later became Chicago’s top radio personality, promoted shows here in the 1930s and sang with the Leaners Band, which featured George Leaner on piano. Lillian McMurry of Trumpet Records, whose offices were located on the same block, attended gospel shows here to discover talent. Blues pianist Otis Spann recalled winning an Alamo talent contest as a child, and other local artists who competed included Sam Baker, Jr., Mel Brown, Sam Myers, Cadillac George Harris, Little Jeno Tucker, Tommy Tate, Amanda Humphrey (Bradley), Roosevelt Robinson, the vocal group the Quails (Dequincy Johnson, George Jackson, and Sam Jones), and Albert Goodman, later of the Moments and the trio Ray, Goodman & Brown. During the 1950s and ’60s Jobie Martin of Jackson’s WOKJ radio emceed the contests.

The Alamo closed in the 1980s and, following extensive renovation, reopened under non-profit ownership in 1997. The theatre began to celebrate Farish Street’s musical legacy again with occasional music programs, and in 2000 Jackson bluesman Eddie Cotton, Jr., recorded his CD Live at the Alamo Theatre here.

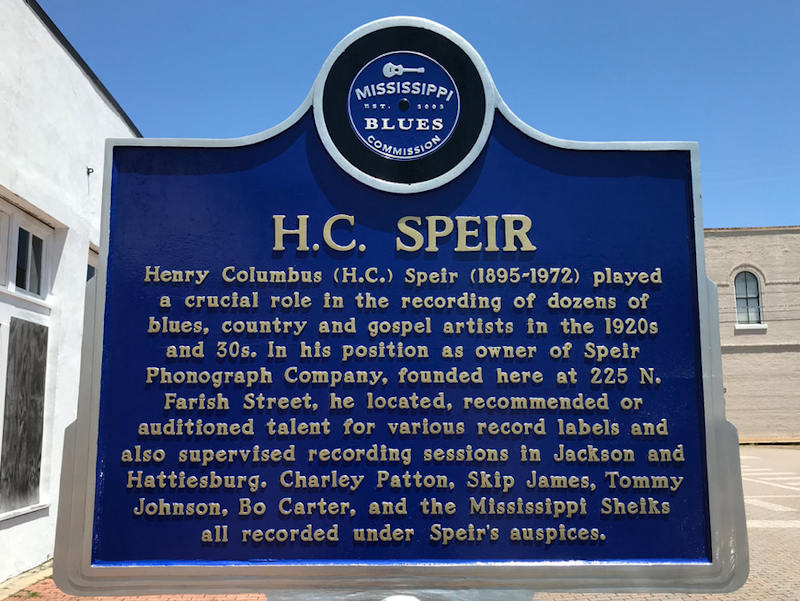

Full text:

Henry Columbus (H.C.) Speir (1895-1972) played a crucial role in the recording of dozens of blues, country and gospel artists in the 1920s and 30s. In his position as owner of Speir Phonograph Company, founded here at 225 N. Farish Street, he located, recommended or auditioned talent for various record labels and also supervised recording sessions in Jackson and Hattiesburg. Charley Patton, Skip James, Tommy Johnson, Bo Carter, and the Mississippi Sheiks all recorded under Speir’s auspices.

H.C. Speir did not own a record label or a music publishing company and his name did not appear on records, but he was responsible for facilitating a wealth of historic recordings by many legendary artists. At his store he made test recordings which he would send to Victor, Columbia, OKeh, Brunswick/ARC, Paramount or Gennett, and if a company approved the artists, Speir would sometimes accompany them to recording sessions in New Orleans, Birmingham, Grafton, Wisconsin, and other cities. During his travels he also scouted for talent in the South and Midwest and even in Mexico. At other times record companies called on Speir to organize sessions in Mississippi.

Speir’s entrée into the record business came in New Orleans where he worked assembling phonographs before he moved to Jackson. Born into a farming family on October 6, 1895, in Prospect, Mississippi, Speir lived in Sebastopol and Walnut Grove and served briefly in the U.S. Navy after graduating from high school in Harpersville. He studied agriculture at Mississippi A&M College (now Mississippi State). He dated his start in Jackson at 1920 although he said he did not open his own business until 1925. He first worked at several local stores, including Batte Furniture Co., where he was advertised as a “first class Talking Machine Mechanic.”

Notable artists who recorded under Speir’s auspices included Charley Patton, Tommy Johnson, Bo Carter, the Mississippi Sheiks, Skip James, Ishmon (Ishman) Bracey, Robert Wilkins, the Mississippi Jook Band (featuring Blind Roosevelt Graves and Cooney Vaughn), and country performers Uncle Dave Macon and the Leake County Revelers. Speir set up recording sessions for OKeh Records at the King Edward Hotel in 1930 and for the Brunswick/American Record Corporation group at the Crystal Palace on Farish Street in 1935 and in Hattiesburg in 1936. Brunswick/ARC released records on Vocalion, Melotone and other labels. Robert Johnson’s iconic Vocalion records reportedly came about through a recommendation from Speir. Houston Stackhouse recalled that Johnson got a new set of guitar strings at Speir’s in preparation for a trip to record in Dallas. Son House remembered auditioning for Speir with Charley Patton and Willie Brown in a gospel group, the Locust Ridge Saints, and among the many others who showed up at Speir’s in hopes of recording were Sonny Boy Williamson (Rice Miller), Big Walter Horton and Honeyboy Edwards.

Speir moved from 225 to 111 North Farish in December of 1931 and relocated to 205 West Capitol Street in 1936 and 206 West Capitol in 1938, finally selling the business in 1943 and establishing Speir’s Trading Post on Pocahontas Road. Speir placed ads for all his stores in the Clarion-Ledger, often with photos of himself. All along, he had been investing in real estate, and he made his living as a realtor during his final years. He was also an avid organic gardener, birdwatcher and Biblical scholar, and the Clarion-Ledger reported in 1971: “Speir is most known for his generosity, giving away vegetables and flower bouquets to the sick and to most everyone.” Speir died on April 22, 1972, and was buried at Lakewood Memorial Park, 6000 Clinton Boulevard in Jackson.

Full text:

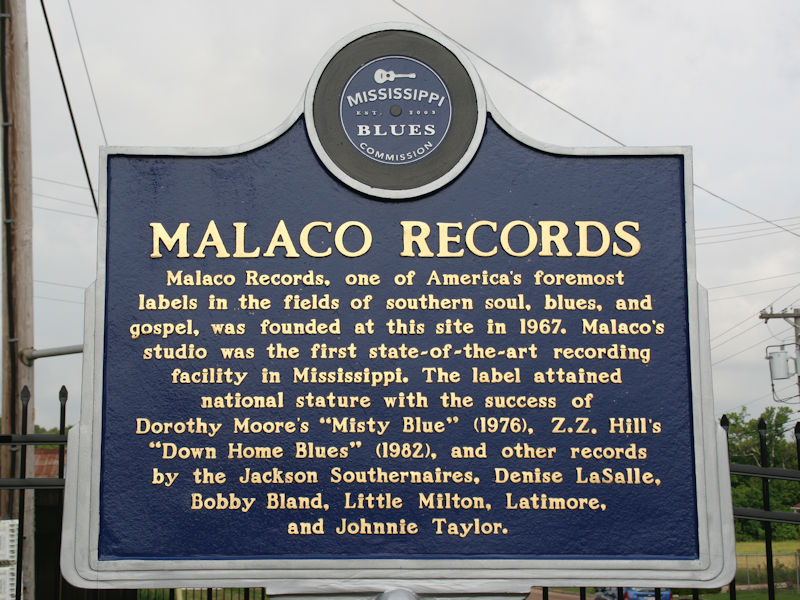

Malaco Records, one of America’s foremost labels in the fields of southern soul, blues, and gospel, was founded at this site in 1967. Malaco’s studio was the first state-of-the-art recording facility in Mississippi. The label attained national stature with the success of Dorothy Moore’s “Misty Blue” (1976), Z.Z. Hill’s “Down Home Blues” (1982), and other records by the Jackson Southernaires, Denise LaSalle, Bobby Bland, Little Milton, Latimore, and Johnnie Taylor.

Malaco Records released its first record, a 45 rpm soul single by Cozy Corley from Hattiesburg, in 1968. By then the company had already been in business for several years as a booking agency, Malaco Attractions, founded by Tommy Couch and Mitch Malouf. Couch and fraternity brother Gerald “Wolf” Stephenson had booked bands as college students at Ole Miss in the early and mid-1960s, and after Stephenson joined the Malaco team, he became chief engineer at the studio which Malaco built at this site in 1967. Malouf left the business in 1975, but Couch continued with Stephenson and, later, Stewart Madison as partners.

During the 1960s and ‘70s, Malaco often worked with larger companies such as Capitol, ABC, Mercury, Atlantic, Stax, and T.K. to release and distribute the recordings produced here. Malaco specialized in rhythm & blues or soul music, although more traditional blues was occasionally recorded here, most notably the 1969 Mississippi Fred McDowell album I Do Not Play No Rock ‘n’ Roll. Among the ‘70s R&B hits produced at Malaco were “Groove Me” by King Floyd on Malaco’s subsidiary label, Chimneyville; “Mr. Big Stuff” by Jean Knight on Stax Records; and the first Top Ten hit on Malaco Records, “Misty Blue” by Jackson singer Dorothy Moore. But it was the album Down Home by Z. Z. Hill that established Malaco’s reputation in the blues. The LP stayed on the Billboard rhythm & blues charts for a phenomenal 93 weeks in 1982-83 while selling half a million copies -– an unprecedented mark for a blues LP. Its success proved that there was still a substantial audience for the blues, and its production style set a standard for much of the music that followed.

Utilizing top-notch songwriters (George Jackson in particular) and skilled arrangers and studio musicians, Malaco blended elements of blues and soul music on further albums by Hill and other singers who joined the Malaco stable, including Denise LaSalle, Latimore, Little Milton, Bobby Bland, Johnnie Taylor, Shirley Brown, Tyrone Davis, Floyd Taylor, and Marvin Sease. Groups such as the Jackson Southernaires, the Williams Brothers, and the Mississippi Mass Choir earned Malaco renown as one of the country’s top gospel labels as well. Other blues and southern soul artists, including Mel Waiters, Bobby Rush, Artie “Blues Boy” White, and Poonanny, recorded for Waldoxy, a label launched by Tommy Couch, Jr., in 1992. Many Malaco hits, including “Down Home Blues,” “The Blues is Alright,” “Someone Else is Steppin’ In,” “Members Only,” and “Last Two Dollars,” have become staples in the repertoires of blues bands across the country.

Full text:

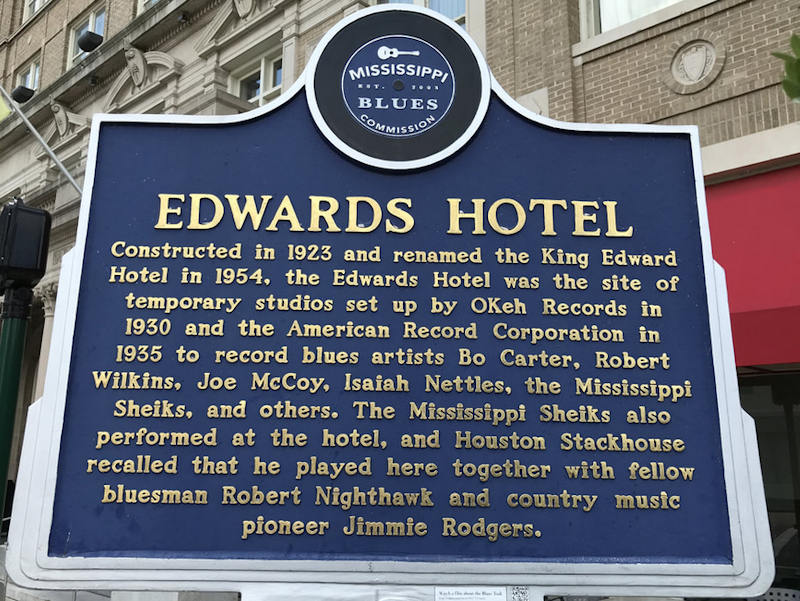

Constructed in 1923 and renamed the King Edward Hotel in 1954, the Edwards Hotel was the site of temporary studios set up by OKeh Records in 1930 and the American Record Corporation in 1935 to record blues artists Bo Carter, Robert Wilkins, Joe McCoy, Isaiah Nettles, the Mississippi Sheiks, and others. The Mississippi Sheiks also performed at the hotel, and Houston Stackhouse recalled that he played here together with fellow bluesman Robert Nighthawk and country music pioneer Jimmie Rodgers.

The Edwards Hotel, housed in a luxurious, twelve-story Beaux Arts style building, would appear at first glance to be an odd place to make blues recordings. The first hotel on the site, the Confederate House, was built in 1861, and after its destruction by General Sherman’s forces in 1863 it was rebuilt in 1867 as the three-story Edwards House. The Edwards Hotel was constructed in 1923, and soon became a favorite lodging and deal-making place for state legislators. Its role as a recording studio stemmed from the fact that prior to World War II all major recording companies were located in the North, and Southern-based artists often had to travel hundreds of miles to record. An occasional solution was setting up temporary facilities at hotels, and in Jackson the OKeh and ARC companies turned to H. C. Speir, a talent scout who operated Speir Phonograph Company on nearby North Farish Street.

Speir had previously discovered blues artists Charley Patton and Tommy Johnson and sent them to other cities to record. Together with Polk Brockman of OKeh, Speir arranged the first sessions in Mississippi in December of 1930 at the Edwards Hotel. Blues performers at the sessions included the Mississippi Sheiks, an African American string band from the Bolton/Edwards area, who had recorded the massive hit Sitting On Top of the World for OKeh earlier in 1930. Individual members of the Sheiks’ rotating cast also recorded at the hotel, including the duo of guitarists Bo Carter (Chatmon) and Walter Jacobs (Vinson), and mandolinist Charlie McCoy, a native of Raymond. Other artists included Caldwell Bracey and his wife Virginia from Bolton, who recorded both gospel and blues (as “Mississippi” Bracy [sic]), the gospel duo of “Slim” Duckett and “Pig” Norwood, and Elder Charlie Beck and Elder Curry, who both recorded sermons. The sessions were also notable for capturing white Mississippi string bands, the Newton County Hill Billies and Freeny’s Barn Dance Band (from Leake County) as well as Tennessee-based country music pioneer Uncle Dave Macon.

In 1935 Speir set up a second series of sessions at the Edwards Hotel for ARC, which operated Vocalion and several other labels. The most prominent artist was Memphis bluesman Robert Wilkins, a native of Hernando who recorded as “Tim Wilkins.” Also recorded were pianist Harry Chatmon, brother of Bo Carter, and obscure and colorfully named artists Sarah and Her Milk Bull, the Delta Twins, Kid Stormy Weather, Blind Mack, and the Mississippi Moaner, aka Isaiah Nettles, a Copiah County native whose sole single, Mississippi Moan/It’s Cold In China, is widely regarded as a classic of early Mississippi blues.

Full text:

During the era of segregation, traveling African Americans had few options for lodging. In Jackson, many black musicians stayed at the Summers Hotel, established in 1944 by W.J. Summers. In 1966 Summers opened a club in the hotel basement that he called the Subway Lounge. The Subway was a regular jazz venue and offered popular late night blues shows from the mid-1980s until the hotel’s demolition in 2004.

During the segregated 1940s, ’50s, and ’60s, the two main Jackson hotels open to African Americans were the Edward Lee Hotel on Church Street and the Summers Hotel. The Summers Hotel, originally the Maples, a rooming house for whites, stood here at 619 W. Pearl Street. The building was remodeled and renamed the Summers Hotel in 1943 after its purchase by W. J. Summers (1897-1977), a prominent African American businessman, who ran the hotel with his wife Elma. The hotel was popular among touring musicians, including James Brown, Hank Ballard, and Nat “King” Cole.

In 1966 Summers enlisted Jimmy King—vocalist, bandleader, and high school teacher—to run a newly constructed basement lounge, which King dubbed the Subway. In the ’60s and ’70s the Subway Lounge featured mostly jazz performers, including King, brothers Kermit, Jr., Sherrill, and Bernard Holly, and organist Levon Mitchell, as well as various touring or area groups.

In 1969 King left the Subway to start his own club but returned in 1986, when he and his wife Helen revived it as a late-night blues venue, with music starting at midnight. Guitarist Jesse Robinson led the initial house band, the Knee Deep Band, which was followed by the House Rockers, fronted by singers Levon Lindsey and Abdul Rasheed, and the King Edward (Antoine) Blues Band. Knee Deep Band vocalist Walter Lee “Big Daddy” Hood was billed as “500 Pounds of Blues.” Other Jackson artists who performed at the Subway included Eddie Cotton, Jr., Bobby Rush, Patrice Moncell, Eddie Rasberry, Sam Myers, J. T. Watkins, Pat Brown, Dennis Fountain, Dwight Ross, Greg “Fingers” Taylor, Thomas “Snake” Johnson, Vasti Jackson, Bill Sampson, and the Juvenators.

In April 2002 director Robert Mugge filmed performances at the Subway Lounge for the documentary Last of the Mississippi Jukes, which was released in early 2003. The documentary addressed the Subway’s history and its diverse clientele, as well as efforts to save the club despite the building’s serious structural problems. The efforts failed, and the Subway closed following a final performance in April 2003. The building was demolished in 2004.

Full text:

Scott Radio Service Company, located at 128 North Gallatin Street, just north of this site, was one of the first businesses in Mississippi to offer professional recording technology. The Jackson-based Trumpet record label used the Scott studio for sessions with blues legends Sonny Boy Williamson (Rice Miller) and Elmore (Elmo) James, along with many other blues, gospel, and country performers, from 1950 to 1952. Owner Ivan M. Scott later moved the company to 601C West Capitol Street.

Mississippi is famed as a rich source of musical talent, but few artists were commercially recorded in the state prior to World War II. Recording technology was prohibitively expensive and most studios were located in northern cities, although companies sometimes sent teams south to set up equipment in hotel rooms or other facilities to record local artists. The OKeh label recorded in Jackson in 1930 and the American and Brunswick record corporations did sessions in Jackson in 1935 and Hattiesburg in 1936, but otherwise the only early blues recordings done in Mississippi were conducted by folklorists, including John A. and Alan Lomax, using bulky portable equipment.

In the wake of World War II dramatic technological, social, legal, and economic developments transformed the recording industry. Many new independent labels emerged, often catering to the new rhythm & blues and country & western markets, including Jackson’s Trumpet Records, founded by Willard and Lillian McMurry. The label initially had to outsource the recording of artists, and held its first session in April of 1950 at local radio station WRBC, which like many other stations at the time had equipment for recording commercials and in-house programming. In November of that year Trumpet began recording country, gospel, and blues artists at Scott Radio Service Company, operated by Ivan M. Scott (1907-1986), a Florida native who came to Jackson in the 1930s. Scott, who worked at various times as an appliance repairman, Columbia Records representative, jukebox operator, WRBC radio engineer, and communications consultant, opened shop here with Ernest A. Bradley, Jr., under the name Radio Service Company around 1947. Scott, who soon became sole owner of the firm, recorded music on a disc cutting machine for the Trumpet sessions, although many recording studios were using tape by the early ’50s.

Scott engineered more than seventy recordings for Trumpet, including the first releases by Elmore James (“Dust My Broom”) and Sonny Boy Williamson No. 2 (“Eyesight to the Blind”), as well as sides by bluesmen Big Joe Williams, Arthur “Big Boy” Crudup, Willie Love, Luther and Percy Huff, Earl Reed, Clayton Love, Bobo “Slim” Thomas, Lonnie Holmes, and Sherman Johnson. Prior to establishing their own Diamond Studio in 1954, the McMurrys also issued recordings made at radio stations including Hattiesburg’s WFOR and Laurel’s WLAU and at studios including Sam Phillips’s Memphis Recording Service and Ammons Studio (later Delta Recording Company) in Jackson. Jimmie Ammons recorded a wide variety of music and issued records by blues artists Tommy Lee (Thompson), Little Milton Anderson, and Tabby Thomas on his Delta label.

Full text:

The Queen of Hearts, a primary venue for down-home blues in Jackson, opened at this location in the 1970s. During the following decades, owner-operator Chellie B. Lewis presented the blues bands of King Edward, Sam Myers, Big Bad Smitty, and many others. The house behind the club at 905 Ann Banks Street was owned and occupied in the 1960s by blues singer-guitarist Johnnie Temple, who had been a popular recording artist in Chicago in the 1930s and ‘40s.

Jackson became an important center for the blues in the early 1900s, when musicians from rural communities came here to play for crowds on the capital city’s streets and in its many venues. Live blues continued to thrive in Jackson into the twenty-first century, thanks to clubs such as the Queen of Hearts, where owner Chellie B. Lewis booked musicians and cooked soul food every weekend for decades. A native of Bolton, Mississippi, Lewis opened the club as “Nina’s Lounge” after taking over the lease from Mose Chinn, whose brother Clarence ran the popular New Club Desire in Canton. Lewis had previously operated a “whiskey house” with a jukebox in the nearby Maple Street Apartments and worked as a waiter at Percy Simpson’s nightclub on Moonbeam Street, where he would sometimes play piano with Elmore James’s band.

John “Big Bad Smitty” Smith, a native of Vicksburg, was the first featured musician at the Queen of Hearts and was followed by bands led by King Edward (Antoine), Cadillac George Harris, Tommy “T. C.” Carter, Norman Clark, and Roosevelt Robinson, Jr. Others who performed or sat in at the Queen of Hearts included Sam Myers, McKinley Mitchell, King Edward’s brother Nolan Struck, Prentiss Lewis, Charlie Jenkins, Johnny Littlejohn, Levon Lindsey, brothers “Lightnin’” and Little Charles Russell, Elmore James, Jr., Robert Robinson, Andrew “Bobo” Thomas, Tommy Lee Thompson, Bobby Rush, Z. Z. Hill, Little Milton, Dorothy Moore, Lee “Shot” Williams, Abdul Rasheed, Eddie Rasberry, Walter Lee “Big Daddy” Hood, J. T. Watkins, Roosevelt Robinson, Sr., George Jackson, Eddie Cotton, Jr., Sam Baker, Jr., Jesse Robinson, Bill Simpson, Louis “Gearshifter” Youngblood, Robert “Bull” Jackson, Greg “Fingers” Taylor, Willie (Dee) Dixon, Robert “The Duke” Tillman, Sweet Miss Coffy, Willie James Hatten, Billy “Soul” Bonds, Frank-O (Johnson), Tina Diamond, Dennis Fountain, Marvin Bradley, James Williams, Sugar Lou, and Debra K.

Lewis also rented out rooms above the Queen of Hearts to musicians including Sam Myers and Big Bad Smitty, and recalled that the home of bluesman Johnnie Temple (1905-1968), located behind the club, was a popular hangout for Elmore James, Sonny Boy Williamson No. 2, and other musicians. The house was previously occupied by Temple’s stepfather, guitarist Lucine “Slim” Duckett, who recorded in Jackson for the OKeh label in 1930. Tommy Johnson and Skip James were among other noted blues performers who stayed with the Duckett/Temple family at various houses in Jackson. After moving to Chicago in the 1930s Temple recorded extensively, scoring his biggest hit with the often-covered “Louise Louise Blues.” He returned to Jackson in the late 1950s.

Full text:

This area of Rankin County, formerly called East Jackson and later the Gold Coast, was a hotbed for gambling, bootleg liquor, and live music for several decades up through the 1960s. Blues, jazz, and soul performers, including touring national acts and locally based artists Elmore James, Sonny Boy Williamson No. 2 (Rice Miller), Sam Myers, Cadillac George Harris, and Sam Baker, Jr., worked at a strip of clubs along Fannin Road known to African Americans as “’cross the river.”

Mississippi state law prohibited the sale of liquor from 1908 to 1966, but humorist Will Rogers purportedly observed, “Mississippians will vote dry as long they can stagger to the polls.” By the 1930s bootleggers had set up shop openly here on the “Gold Coast,” a name that likely derived from the area’s proximity to the Pearl River and the vast amounts of money that were made here from bootlegging, gambling, and other vices. The Gold Coast soon became notorious for its boisterous nightlife, frequent murders, and official corruption, but customers continued to stream in from considerably stricter Jackson. On occasion the Mississippi National Guard was brought in to shut down the area, albeit with only temporary success, and the day-to-day operations and fortunes of bootleggers and clubs depended largely on the whims of local sheriffs. Infamous bootleggers included G. W. “Big Red” Hydrick and Sam Seaney, a club owner who was killed in a 1946 shootout that also claimed the life of Rankin County constable Norris Overby.

Blues activity “’cross the river” centered on Fannin Road, where dozens of venues ranging from elaborate clubs to informal juke joints were frequented and mostly owned by African Americans. Many businesses stayed open twenty-hours a day, seven days a week. By the 1940s many national blues and jazz acts were playing at the Blue Flame/Play House complex, run by Joe Catchings, and at the Rankin Auditorium behind the Stamps Brothers Hotel, operated by brothers Charlie, Clift, and Bill Stamps. The Auditorium advertised that its dance floor could accommodate three thousand people, and other reports noted that white patrons were provided balcony seating.

By the mid-‘50s local clubs including the Blue Flame, Rocket Lounge, the Heat Wave, the Last Chance, and the Gay Lady featured mostly local artists. Among these were Sam Myers, King Mose, Cadillac George Harris, brothers Charley and Sammie Lee Smith, Jimmy King, Jesse Robinson, Charles Fairley, Willie Silas, Bernard “Bunny” Williams, brothers Kermit, Jr., Bernard, and Sherrill Holly, brothers Curtis and J.T. Dykes, Milton Anderson, Booker Wolfe, Tommy Tate, Robert Broom, Charles Fairley, Joe Chapman, and Sam Baker, Jr., whose parents ran the Heat Wave.

In 1966 Mississippi became the last state in the union to end prohibition, and gave individual counties the choice of remaining “dry” or becoming “wet.” Ironically, Rankin County chose the former, while neighboring and more populous Hinds County chose the latter. With these decisions the rationale for the Gold Coast was gone, and the club scene and bootlegging operations came abruptly to a stop.

Full text:

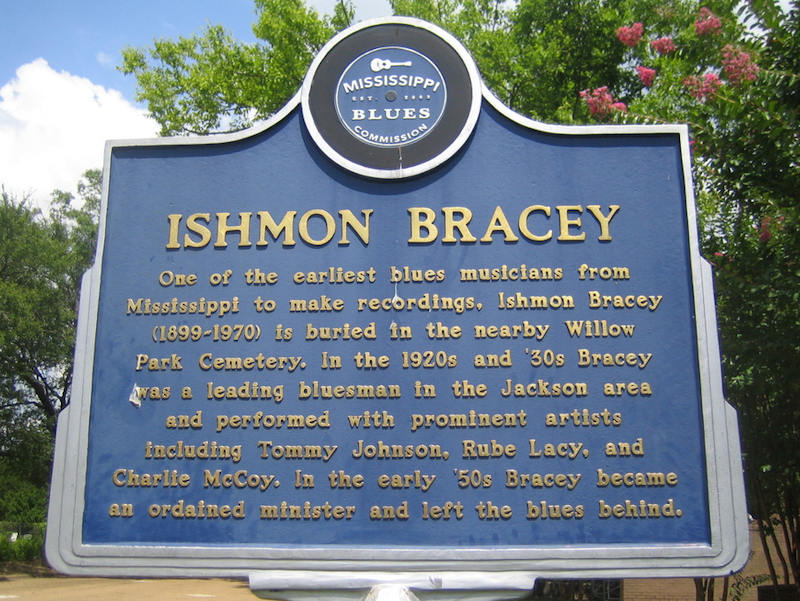

One of the earliest blues musicians from Mississippi to make recordings, Ishmon Bracey (1899-1970) is buried in the nearby Willow Park Cemetery. In the 1920s and ‘30s Bracey was a leading bluesman in the Jackson area and performed with prominent artists including Tommy Johnson, Rube Lacy, and Charlie McCoy. In the early ‘50s Bracey became an ordained minister and left the blues behind.

Bracey was born in Byram, about ten miles south of Jackson, in January 1899, according to census records. He learned guitar from locals Louis Cooper and Lee Jones and moved to Jackson in the late 1920s after encountering Tommy Johnson, one of Mississippi’s most prominent bluesmen, in Johnson’s longtime home of Crystal Springs. Bracey soon became one of the most popular musicians in the Jackson area’s vital blues scene, which consisted largely of musicians who were likewise born in small communities in the area. These included Johnson, his brothers LeDell, Clarence, and Mager, and R. D. “Peg Leg Sam” Norwood of Crystal Springs; Rubin Lacy, Shirley Griffith, John Henry “Bubba” Brown, “Son” Spand , and brothers Luther and Percy Huff, all of Rankin County; brothers Joe and Charlie McCoy of Raymond; Johnnie Temple of Canton; Lucien “Slim” Duckett of Tylertown; and, from Bolton, Walter Vinson, Caldwell “Mississippi” Bracy, and the Chatmon family (brothers Bo, Harry, Lonnie, and several others).

Jackson blues in the 1920s had a lighter feel than its counterpart in the Delta and sometimes featured the mandolin and the fiddle. Bracey and other musicians often played at dances for both black and white audiences, performing waltzes and ragtime numbers, and otherwise serenaded passersby on the busy streets of Jackson. Bracey’s music came to broader attention after he auditioned for recording agent H. C. Speir, who operated a furniture store on North Farish Street. Speir arranged for Bracey and Tommy Johnson to make their debut recordings at a session for Victor in Memphis in February of 1928. At that session and another for Victor later that year, Bracey was accompanied on guitar and mandolin by Charlie McCoy. Bracey recorded in more of a jazz mode in late 1929 and early 1930 for the Paramount label in Grafton, Wisconsin, backed by the New Orleans Nehi Boys (Charlie Taylor on piano and “Kid” Ernest Moliere on clarinet, an instrument rarely heard on Mississippi blues recordings). Bracey’s musical breadth is suggested in the 1930 census, where his occupation is listed as a musician in a “hotel orchestra.”

By the mid-‘30s many of the musicians in Bracey’s circle had left the area, and his musical partnership with Tommy Johnson ended. In later city directories he is listed as a laborer or painter. In 1963, when blues researcher Gayle Dean Wardlow met and interviewed him in Jackson, Bracey had been a Baptist minister for over a decade, and, although he would no longer play blues, he provided important information on the early blues scene in Jackson. He died on Feb. 12, 1970.

Full text:

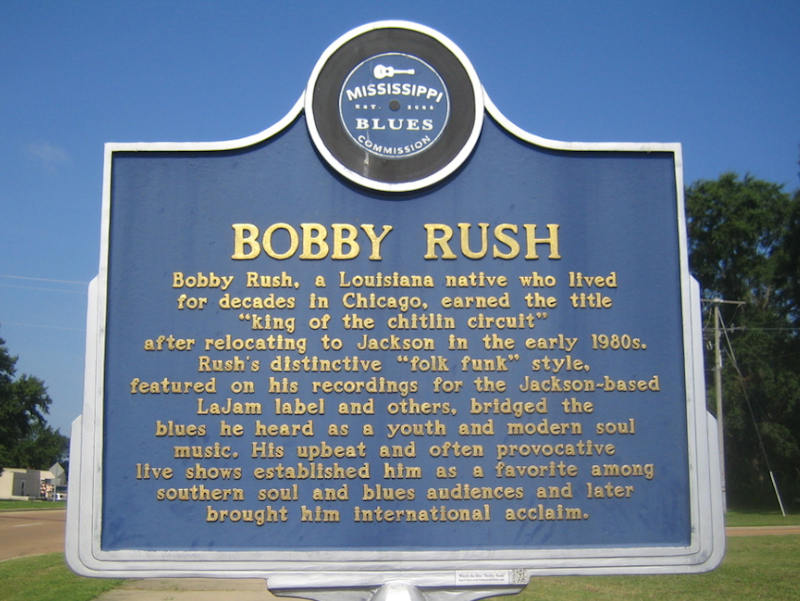

Bobby Rush, a Louisiana native who lived for decades in Chicago, earned the title “king of the chitlin circuit” after relocating to Jackson in the early 1980s. Rush’s distinctive “folk funk” style, featured on his recordings for the Jackson-based LaJam label and others, bridged the blues he heard as a youth and modern soul music. His upbeat and often provocative live shows established him as a favorite among southern soul and blues audiences and later brought him international acclaim.

He was born Emmett Ellis, Jr., on November 10, 1937 (although he has claimed birthdates before and after that date) in Homer, Louisiana, and at eleven moved with his family to Pine Bluff, Arkansas. He eventually took the stage name “Bobby Rush” out of respect for his father, who was a preacher. Rush built his first instrument, a one-stringed “diddley bow,” and by his teens was donning a fake mustache and playing at local juke joints and on the road with bluesmen including Elmore James, Boyd Gilmore, and John “Big Moose” Walker. After moving to Chicago in the 1950s, he worked with Earl Hooker, Luther Allison, and Freddie King. Rush, who played guitar, bass, and harmonica, developed a lively and sometimes risque stage act that blended music, dance, and comedy. His musical approach—which he later coined “folk funk”—married various contemporary sounds with lyrical themes that often borrowed from African American folklore and traditional blues. He achieved renown for his entrepreneurial flair by working multiple gigs the same night and sometimes collecting double pay by disguising himself as an emcee at his own shows. He also booked and promoted many shows himself rather than working through an agency.

Rush’s initial 45 rpm singles appeared in the 1960s on various Chicago labels, including Jerry-O, Salem, and Checker. His first national hit was “Chicken Heads” on the Galaxy label in 1971. Jewel, ABC, Warner Brothers, and London also released Rush 45s, and his first LP appeared on Philadelphia International. In 1982 he began recording for LaJam, a Jackson label owned by Como native James Bennett, who recorded blues, gospel, and R&B acts for his J&B, Traction, Retta’s, MT, Big Thigh, and “T” labels. Rush also moved from Illinois to Jackson in order to be closer to his largely southern fan base. He scored a hit with “Sue” on LaJam and maintained a strong following on the southern soul circuit during the following decades with his tireless rounds of performances and further hits on LaJam, Urgent!, and the Jackson-based Waldoxy label, including “What’s Good For the Goose (Is Good For the Gander Too),” “Hen Pecked,” “I Ain’t Studdin’ You,” “Hoochie Man,” “Booga Bear,” “A Man Can Give It (But He Can’t Take It),” and “You, You, You (Know What to Do).”

In the 1990s Rush began to “cross over” to white audiences, and in 2003 his dynamic stage show was captured in Richard Pearce’s documentary The Road To Memphis, part of the PBS series Martin Scorsese Presents The Blues. The same year Rush formed his own Deep Rush label, on which he released special projects including a DVD, Live at Ground Zero, and an acoustic album, Raw. A recipient of multiple blues awards, Rush was inducted into the Blues Hall of Fame in 2006. He won a GRAMMY® in 2017 for Best Traditional Blues Album for Porcupine Meat.

Full text:

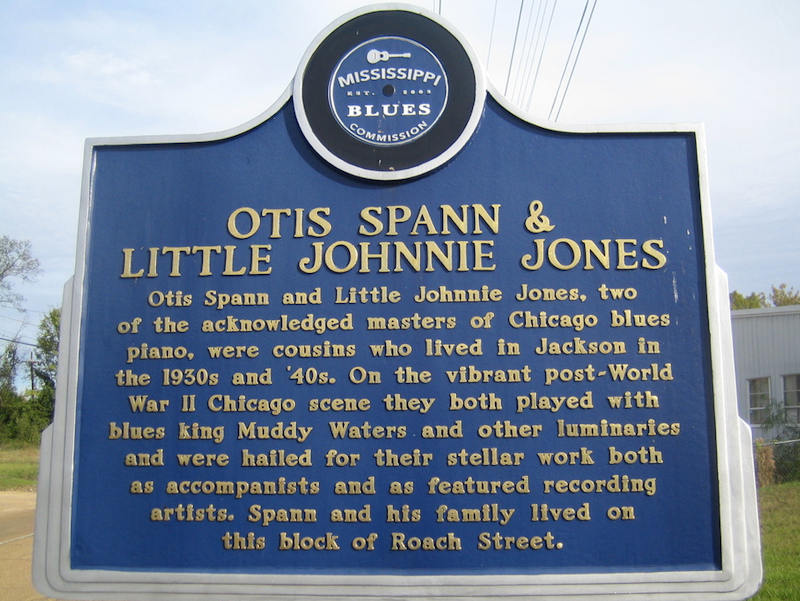

Otis Spann and Little Johnnie Jones, two of the acknowledged masters of Chicago blues piano, were cousins who lived in Jackson in the 1930s and ’40s. On the vibrant post-World War II Chicago scene they both played with blues king Muddy Waters and other luminaries and were hailed for their stellar work both as accompanists and as featured recording artists. Spann and his family lived on this block of Roach Street.

Otis Spann and Little Johnnie Jones grew up playing in church in Jackson, where they also began to focus their highly touted talents on the blues. Piano legend Little Brother Montgomery, who was based in Jackson in the 1930s and ’40s, claimed both Spann and Jones as proteges, and both were also influenced later by Big Maceo in Chicago.

Spann, a longtime member of the Muddy Waters band famed for his rippling piano style and stirring vocals, was the first pianist inducted into the Blues Hall of Fame in 1980. Spann had a fondness for tall tales that resulted in a confusing biography and uncorroborated stories of many exploits. His birth date was usually cited as March 21, 1930, in Jackson, but several documents and many musicians suggested he was older. Spann also told author Paul Oliver that he was from Belzoni, where he learned from pianist Friday Ford. His mother, Josephine Ervin Spann, played blues guitar, and his father, Frank Houston Spann, was a carpenter and pianist. (By Montgomery’s account, however, Spann was the son of Friday Ford.) The Spanns lived in Jackson and Pelahatchie, and Otis was in Plain when he was first married in 1945. Spann’s claim to fame in Jackson was winning a talent contest at the Alamo Theater. In Chicago Spann played on records by Muddy, Howlin’ Wolf, Sonny Boy Williamson, Bo Diddley, Chuck Berry, and others. His own records in the U.S. and Europe featured accompaniments from Muddy, B. B. King, Eric Clapton, and Fleetwood Mac, among others. Spann, who recorded several albums a year in the late ’60s, died in Chicago on April 24, 1970.

Little Johnnie (also spelled Johnie and Johnny) Jones was, like Spann, a well-liked, in-demand pianist in the Chicago clubs and studios. “I wind up teaching him,” Spann once said, “but he beat me at my own game.” Jones was born Johnie McPherson (or McFearson) in Inverness on October 10, 1924. By the late 1930s he was living in Jackson with his mother, Mary, a church pianist, and his stepfather, George Jones, a truck driver and amateur guitarist. In Chicago, Jones played for several years with Tampa Red and recorded with Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, Magic Sam, and others, but was best known for his tenure with Elmore James. Jones, recalled as a fun-loving entertainer with a flair for the risque as well as deep blues, died in Chicago on November 19, 1964.

Other blues and R&B performers who left Jackson for Chicago included Cicero Blake, Hip Linkchain, Melvin Taylor, Dead Eye Norris (aka Sonny Mack), Andrew Brown, the Black Lone Ranger (James Ramsey) and Buddy Scott. Others who migrated north and west included Emmit Slay (to Detroit), Mississippi Johnny Waters (Sandifer), King Solomon and Zac Harmon (to California), Millage Gilbert (to Kansas City), and Mel Brown (to Canada after several other stops).

Source: http://msbluestrail.org/

Photo Gallery

These photos are from a visit to Jackson in 2008; renovation work has now taken place at many historic sites (see Google Maps).

Ross Furniture Store (225 N. Farish St.) the original site of HC Speir’s music shop, now demolished I believe.

Site of Ace Records (241 N. Farish St.), now re-built

Birdland bar (538 N. Farish St.) now converted back to it’s original name ‘Crystal Palace’.

The Alamo Theatre prior to the Blues Trail Marker being erected.

Peaches Restaurant next door to the Alamo Theatre.

B.B. King flagstone on the sidewalk outside Peached Restaurant.