Themed Photo Gallery and Information: Indianola, Mississippi

History

Indianola is a city in Sunflower County, Mississippi, United States, in the Mississippi Delta. The population was 10,683 at the 2010 census. It is the county seat of Sunflower County.

The town was originally named “Indian Bayou” in 1882 because the site along the river bank was formerly inhabited by a Choctaw Indian village. Between 1882 and 1886, the town’s name was changed from “Indian Bayou” to “Eureka,” then to “Belengate,” and finally “Indianola,” which was allegedly in honor of an Indian princess named “Ola.” The town population developed at the site because of the location of a lumber mill on the river.

In 1891, Minnie M. Cox was appointed postmaster of Indianola, becoming the first black female postmaster in the United States. Her rank was raised from fourth class to third class in 1900, and she was appointed to a full four-year term. Cox’s position was one of the most respected and lucrative public posts in Indianola, as it served approximately 3,000 patrons and paid $1,100 annually, then a large sum. White resentment to Cox’s prestigious position began to grow, and in 1902 some white residents in Indianola drew up a petition requesting Cox’s resignation. James K. Vardaman, editor of The Greenwood Commonwealth and a white supremacist, began delivering speeches reproaching the people of Indianola for “tolerating a negro [sic] wench as a postmaster.”

Racial tensions grew, and threats of physical harm led Cox to submit her resignation to take effect on January 1, 1903. The incident attracted national attention, and President Theodore Roosevelt refused to accept her resignation, feeling Cox had been wronged, and the authority of the federal government was being compromised. “Roosevelt stood resolute. Unless Cox’s detractors could prove a reason for her dismissal other than the color of her skin, she would remain the Indianola postmistress.”

Roosevelt closed Indianola’s post office on January 2, 1903, and rerouted mail to Greenville; Cox continued to receive her salary. The same month, the United States Senate debated the Indianola postal event for four hours, and Cox left Indianola for her own safety and did not return. In February 1904, the post office was reopened but was demoted in rank from third class to fourth class.

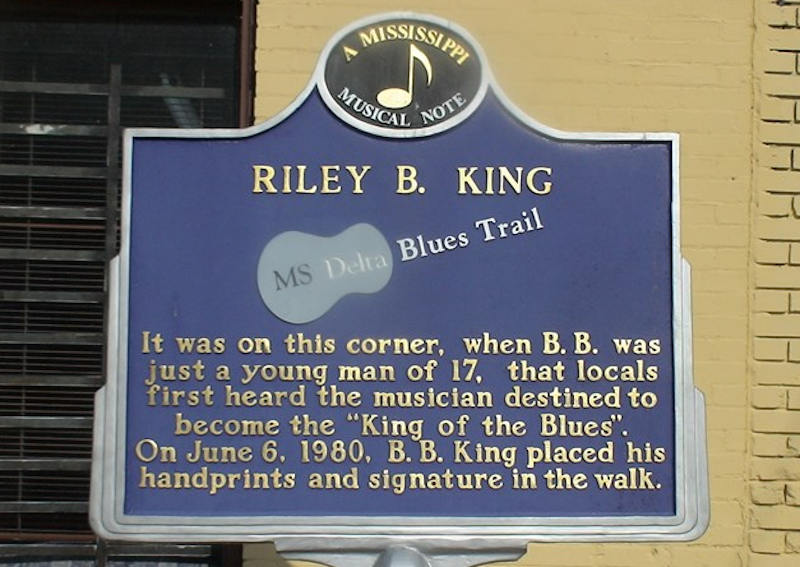

In the early and mid-twentieth century a number of Blues musicians originated in the area, including B.B. King, who worked in the local cotton industry in Indianola in the 1940s before pursuing a professional musical career.

In July 1954, two months after the Supreme Court of the United States announced its unanimous decision in Brown v. Board of Education, ruling that school segregation was unconstitutional, the local plantation manager Robert B. Patterson met with a group of like-minded racists in a private home in Indianola to form the White Citizens’ Council. Its goal was to resist any implementation of racial integration in Mississippi.

The Indianola Historic District was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2009 Todd Moye, author of Let the People Decide: Black Freedom and White Resistance Movements in Sunflower County, Mississippi, 1945–1986, said that “Life in Indianola still moves at a pace established by its distinguishing characteristic, the picturesque and languid Indian Bayou that winds through downtown.”

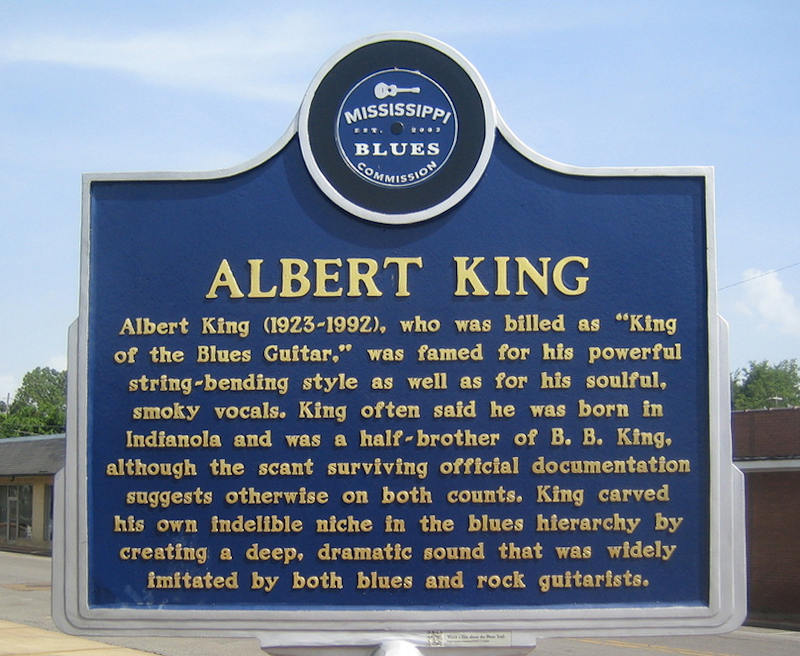

Indianola is the birthplace of the blues musician Albert King. The blues harp player, Little Arthur Duncan, was born in Indianola in 1934. Henry Sloan lived in Indianola, and Charley Patton died near the city.

B.B. King grew up in Indianola as a child. He came to the blues festival named after him every year. King referenced the city with the title of his 1970 album Indianola Mississippi Seeds. The B.B. King Museum and Delta Interpretive Center, a $14 million facility dedicated to King and the blues, opened in September 2008. Many street names are named after King and his music, including B.B. King Road, Lucille St. (named after his guitar), and Delta Blues St.

Source: Wikipedia

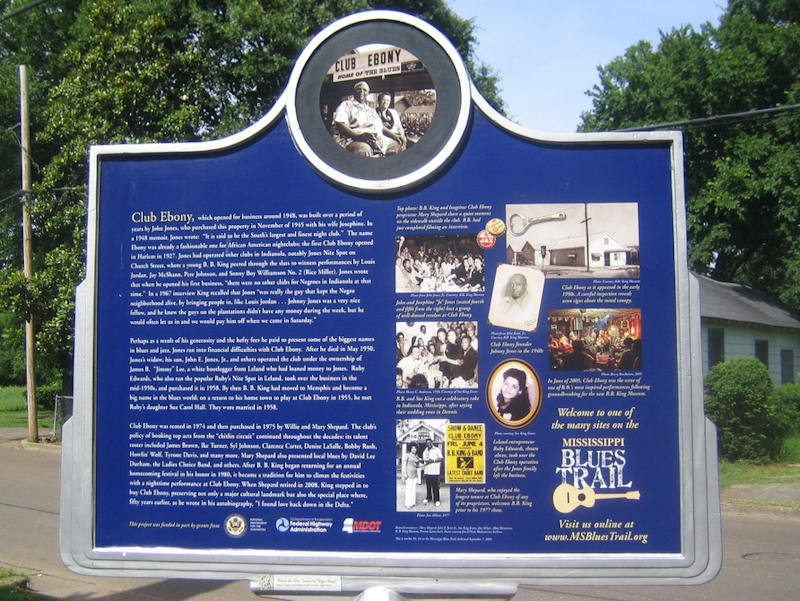

Mississippi Blues Trail Markers

Full text:

Albert King (1923-1992), who was billed as “King of the Blues Guitar,” was famed for his powerful string-bending style as well as for his soulful, smoky vocals. King often said he was born in Indianola and was a half-brother of B. B. King, although the scant surviving official documentation suggests otherwise on both counts. King carved his own indelible niche in the blues hierarchy by creating a deep, dramatic sound that was widely imitated by both blues and rock guitarists.

Albert King’s readily identifiable style made him one of the most important artists in the history of the blues, but his own identity was a longtime source of confusion. In interviews he said he was born in Indianola on April 25, 1923 (or 1924), and whenever he appeared here at Club Ebony, the event was celebrated as a homecoming. He often claimed to be a half-brother of Indianola icon B. B. King, citing the fact that B. B.’s father was named Albert King. But when he applied for a Social Security card in 1942, he gave his birthplace as “Aboden” (most likely Aberdeen), Mississippi, and signed his name as Albert Nelson, listing his father as Will Nelson. Musicians also knew him as Albert Nelson in the 1940s and ’50s. But when he made his first record in 1953–when B. B. had become a national blues star–he became Albert King, and by 1959 he was billed in newspaper ads as “B. B. King’s brother.” He also sometimes used the same nickname as B. B.–“Blues Boy”–and named his guitar Lucy (B. B.’s instrument was Lucille). B. B., however, claimed Albert as just a friend, not a relative, and once retorted, “My name was King before I was famous.”

According to King, he was five when his father left the family and eight when he moved with his mother, Mary Blevins, and two sisters to the Forrest City, Arkansas, area. King said his family had also lived in Arcola, Mississippi, at one time. He made his first guitar out of a cigar box, a piece of a bush, and a strand of broom wire, and later bought a real guitar for $1.25. As a southpaw learning guitar on his own, he turned his guitar upside down. King picked cotton, drove a bulldozer, did construction, and worked other jobs until he was finally able to support himself as a musician.

King’s first band was the In the Groove Boys, based in Osceola, Arkansas. In the early ’50s he also worked with a gospel group, the Harmony Kings, in South Bend, Indiana, and–as a drummer–with bluesman Jimmy Reed in the Gary/Chicago area. He recorded his debut single for Parrot Records in Chicago before returning to Osceola and then moving to Lovejoy, Illinois. Recordings in St. Louis drew new attention to his talents and a stint with Stax Records in Memphis (1966-1974) put his name in the forefront of the blues. Rock audiences and musicians created a new, devoted fan base, while King’s funky, soulful approach helped him maintain a following in the African American community. Among his most notable records were Live Wire/Blues Power, an album recorded at the Fillmore in San Francisco, and the Stax singles “Born Under a Bad Sign,” “Cross Cut Saw,” “The Hunter,” and “I’ll Play the Blues for You.” King remained a major name in blues and was elected to the Blues Hall of Fame in 1983, but he never enjoyed the commercial success that many of his followers (including Eric Clapton and Stevie Ray Vaughan) did. He died after a heart attack in Memphis, his frequent base in his final years, on December 21, 1992.

Full text:

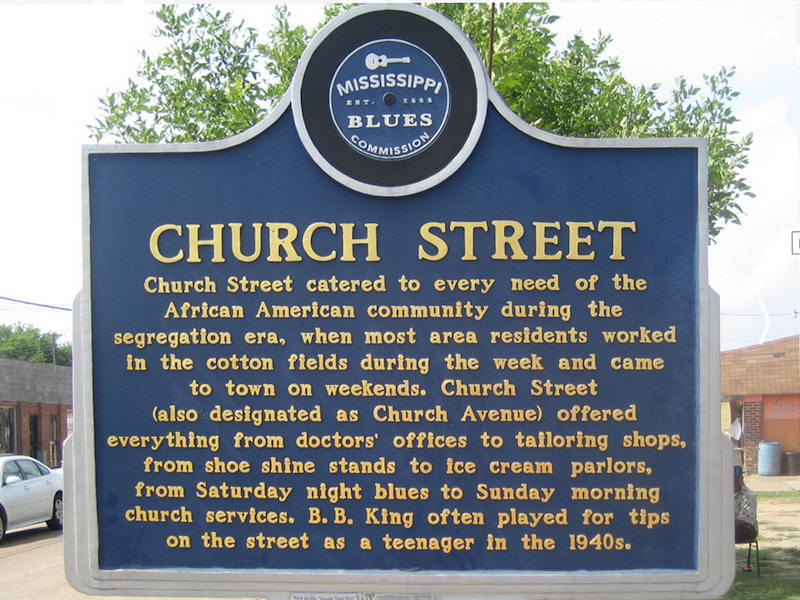

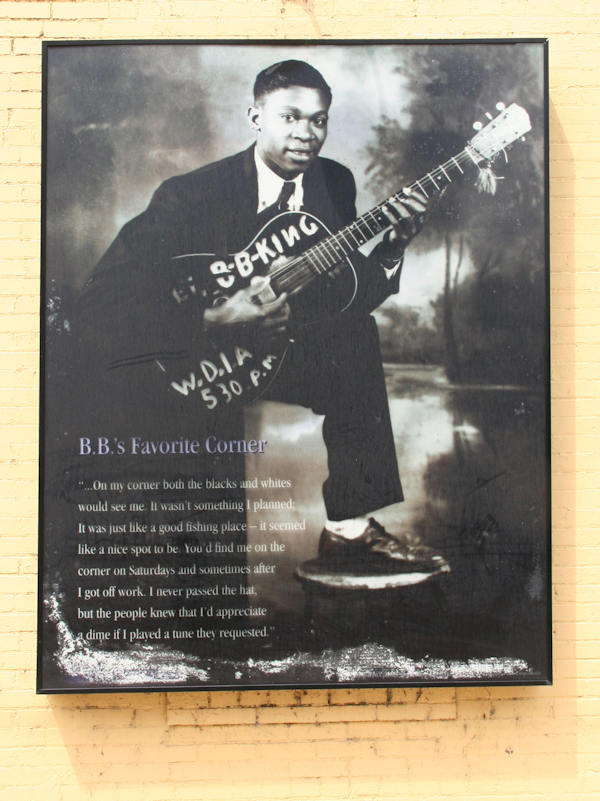

Church Street catered to every need of the African American community during the segregation era, when most area residents worked in the cotton fields during the week and came to town on weekends. Church Street (also designated as Church Avenue) offered everything from doctors’ offices to tailoring shops, from shoe shine stands to ice cream parlors, from Saturday night blues to Sunday morning church services. B. B. King often played for tips on the street as a teenager in the 1940s.

Church Street was once a crowded, bustling thoroughfare where African Americans shopped, socialized, dined, listened to music, and attended church services. In the segregated 1950s, ’60s, and earlier, according to Indianola attorney Carver Randle, “Church Street was an escape valve for black folks. On Saturdays Church Street had a festive kind of Mardi Gras atmosphere. People walked in the street and ate hot tamales and hot dogs and ice cream, drank corn whiskey and ate fish sandwiches. And although that was a tough time for black folks, we were pretty much self contained, all the way from fun to health care. If you made it to Church Street, you were all right.”

When the young B.B. King played on Church Street, he found that churchgoers would give him praise and moral encouragement for performing gospel songs, but tippers were more likely to reward him with money when he played blues. Jones Night Spot on Church Street was then the area’s premier blues venue, presenting bluesmen such as Robert Nighthawk and Robert Jr. Lockwood as well as the big bands of Count Basie and Duke Ellington. Jones later moved to Hanna Street and was renamed the Club Ebony. King appeared there often after turning professional.

Other spots on Church Street, including Sports Place, Stella B.’s, the Pastime Inn, the Cotton Club, the Blue Chip, the Key Hole Inn, Price Night Club, George’s Lounge, and Club Chicago, have offered blues music, most often on jukeboxes, although some have featured live entertainment. Guitarist David Lee Durham (1943-2008), who played with Bobby Whalen in the Ladies Choice Band, once had his own place on Church Street. Other local blues figures have included B.B. King’s cousin Jerry Fair, his wife Galean Fair, and James Earl “Blue” Franklin, a former member of the Greenville band Roosevelt “Booba” Barnes and the Playboys. A Canadian television crew filmed the Barnes group performing at the Key Hole Inn in 1990.

While other notable blues musicians have been born in Indianola, few of them played on Church Street, since most left the area when they were young. These include Albert King (1923-1992), who rivaled B.B. as a blues guitar king; Chicago harmonica players Jazz Gillum (1904-1966, famed for his 1940 recording of “Key to the Highway”) and Little Arthur Duncan (1934-2008); and brothers Louis (1932-1995) and Mac Collins (1929-1997), who were mainstays of the Detroit blues scene. Louis Collins, who performed under the name “Mr. Bo,” and David Durham both developed styles heavily influenced by B.B. King. Another Indianola native, Earl Randle (b. 1947), made his mark in Memphis as a songwriter.

Full text:

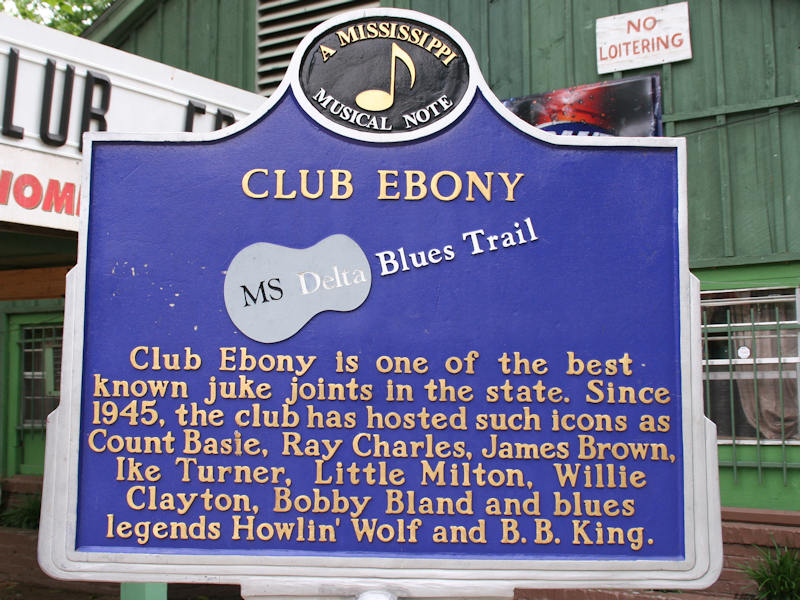

Club Ebony, one of the South’s most important African American nightclubs, was built just after the end of World War II by Indianola entrepreneur Johnny Jones. Under Jones and successive owners, the club showcased Ray Charles, Count Basie, B. B. King, Bobby Bland, Little Milton, Albert King, Willie Clayton, and many other legendary acts. When owner Mary Shepard retired in 2008 after 34 years here, B. B. King purchased the venue to keep the vaunted Club Ebony tradition alive.

The club opened for business around 1948, but was built over a period of years by John Jones, who purchased this property in November of 1945 with his wife Josephine. In a 1948 memoir, Jones wrote: “It is said to be the South’s largest and finest night club.” The name Ebony was already a fashionable one for African American nightclubs; the first Club Ebony opened in Harlem in 1927. Jones had operated other clubs in Indianola, notably Jones Nite Spot on Church Street, where a young B. B. King peered through the slats to witness performances by Louis Jordan, Jay McShann, Pete Johnson, and Sonny Boy Williamson No. 2 (Rice Miller). Jones wrote that when he opened his first business, “there were no other clubs for Negroes in Indianola at that time.” In a 1967 interview King recalled that Jones “was really the guy that kept the Negro neighborhood alive, by bringing people in, like Louis Jordan . . . Johnny Jones was a very nice fellow, and he knew the guys on the plantations didn’t have any money during the week, but he would often let us in and we would pay him off when we came in Saturday.”

Perhaps as a result of his generosity and the hefty fees he paid to present some of the biggest names in blues and jazz, Jones ran into financial difficulties with Club Ebony. After he died in May 1950, Jones’s widow, his son, John E. Jones, Jr., and others operated the club under the ownership of James B. “Jimmy” Lee, a white bootlegger from Leland who had loaned money to Jones. Ruby Edwards, who also ran the popular Ruby’s Nite Spot in Leland, took over the business in the mid-1950s, and purchased it in 1958. By then B. B. King had moved to Memphis and become a big name in the blues world; on a return to his home town to play at Club Ebony in 1955, he met Ruby’s daughter Sue Carol Hall. They were married in 1958.

Club Ebony was rented in 1974 and then purchased in 1975 by Willie and Mary Shepard. The club’s policy of booking top acts from the “chitlin circuit” continued throughout the decades: its talent roster included James Brown, Ike Turner, Syl Johnson, Clarence Carter, Denise LaSalle, Bobby Rush, Howlin’ Wolf, Tyrone Davis, and many more. Mary Shepard also presented local blues by David Lee Durham, the Ladies Choice Band, and others. After B. B. King began returning for an annual homecoming festival in his honor in 1980, it became a tradition for him to climax the festivities with a nighttime performance at Club Ebony. When Shepard retired in 2008, King stepped in to buy Club Ebony, preserving not only a major cultural landmark but also the special place where, fifty years earlier, as he wrote in his autobiography, “I found love back down in the Delta.”

Source : http://msbluestrail.org/

Photo Gallery

These photos were mainly taken during the 2006 “Railroadin’ Some” book signing tour when we spent an afternooon with Mary Shepard, then owner of Club Ebony and an interviewer from the local newspaper. This was of course before the BB King Museum was built.

BB King Mural in a parking lot, 133 2nd Street.

BB KIng Mural at BB KIng Corner, Church Ave & 2nd Street

Rare photo of me

Max Haymes

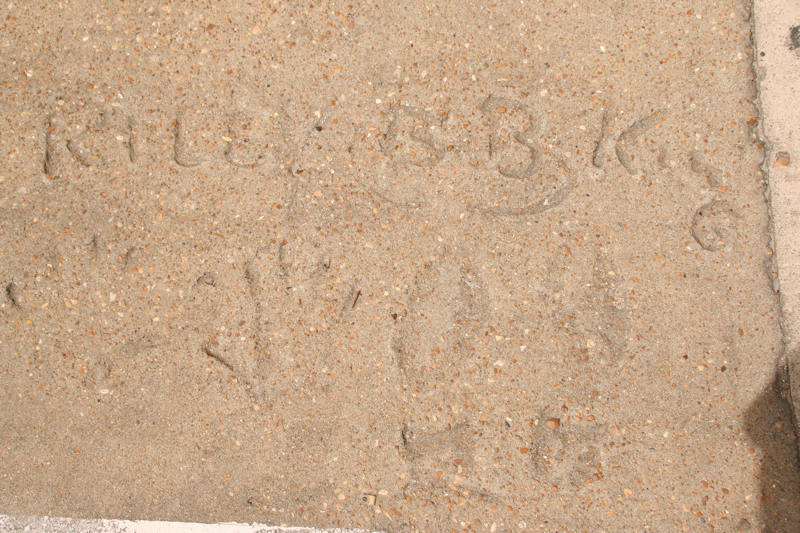

BB King’s hand prints in the sidewalk

Max & Rex Haymes

Building the BB King Museum

The stage in Club Ebony

Posters in Club Ebony

Liza Schnabel, Max Haymes, Rex Haymes and Mary Shepard

Max being interviewed for the local newspaper

Max and Mary Shepard