Themed Photo Gallery and Information: Holly Springs, Mississippi

History

Holly Springs is a city in and the county seat of Marshall County, Mississippi, United States, at the border with southern Tennessee. Near the Mississippi Delta, the area was developed by European Americans for cotton plantations and was dependent on enslaved Africans. After the American Civil War, many freedmen continued to work in agriculture but as sharecroppers and tenant farmers.

As the county seat, the city is a center of trade and court sessions. The population was 7,699 at the 2010 census, slight decrease in population in the 2000 census. The community includes several National Register of Historic Places listed properties and historic districts including Southwest Holly Springs Historic District, Holly Springs Courthouse Square Historic District, Depot-Compress Historic District, and East Holly Springs Historic District. Hillcrest Cemetery in Holly Springs contains the graves of five Confederate generals, and has been referred to as “Little Arlington of the South”.

Holly Springs was founded by European Americans in 1836, on territory occupied by Chickasaw Indians for centuries before Indian Removal. Most of their land was ceded under the Treaty of Pontotoc Creek of 1832. Many early U.S. migrants were from Virginia, supplemented by migrants from Georgia and the Carolinas.

In the city’s founding year of 1836, it had 4,000 European-American residents. A year later, in 1837, records show that forty residents were lawyers, and there were six physicians by 1838. By 1837, the town already had “twenty dry goods stores, two drugstores, three banks, several hotels, and over ten saloons.” It is also home to the Hillcrest Cemetery, built on land given to the city in 1837 by settler William S. Randolph.

Newcomers established the Chalmers Institute, later known as the University of Holly Springs, the oldest university in Mississippi.

The area was developed with extensive cotton plantations dependent on the labor of enslaved African Americans. Many had been transported from the Upper South in the domestic slave trade, breaking up families. The settlement served as a trading center for the neighboring cotton plantations. In 1837, it was made seat of the newly created Marshall County, named for John Marshall, the United States Supreme Court justice. The town developed a variety of merchants and businesses to support the plantations. Its population into the early twentieth century included a community of Jewish merchants, whose ancestors were immigrants from eastern Europe in the 19th century. Even though the cotton industry suffered in the crisis of 1840, it soon recovered.

By 1855 Holly Springs was connected to Grand Junction, Tennessee by the Mississippi Central Railway. In ensuing years, the line was completed to the south of Hill Springs. Toward the end of the 19th century, the Kansas City, Memphis and Birmingham Railroad was constructed to intersect this line in Holly Springs.

During the American Civil War, Union General Ulysses S. Grant used this town temporarily as a supply depot and headquarters. He was mounting a major effort to take the city of Vicksburg on the Mississippi River. Confederate Earl Van Dorn led a raid of the area in December 1862, destroying most of the Union supplies at the Confederate Armory Site. Grant eventually succeeded in ending the siege of Vicksburg with a Union victory.

In 1878, the city suffered a yellow fever epidemic, part of a regional epidemic that spread through the river towns. Some 1,400 residents became ill and 300 died. The existing Marshall County Courthouse, at the center of Holly Springs’ square, was used as a hospital during the epidemic.

After the war and emancipation, many freedmen stayed in the area, working as sharecroppers on former plantations. There were tensions as whites tried to reimpose white supremacy.

As agriculture was mechanized in the early 20th century, the number of farm labor jobs was reduced. From 1900 to 1910, a quarter of the population left the city. Many blacks moved to the North in the Great Migration to escape southern oppression and seek employment in northern factories. The invasion of boll weevils in the 1920s and 1930s, which occurred across the South, destroyed the cotton crops and caused economic problems in the state on top of the Great Depression. Some light industry developed in the area. After World War II, most industries moved to the major cities of Memphis, Tennessee and Birmingham, Alabama.

Source: Wikipedia

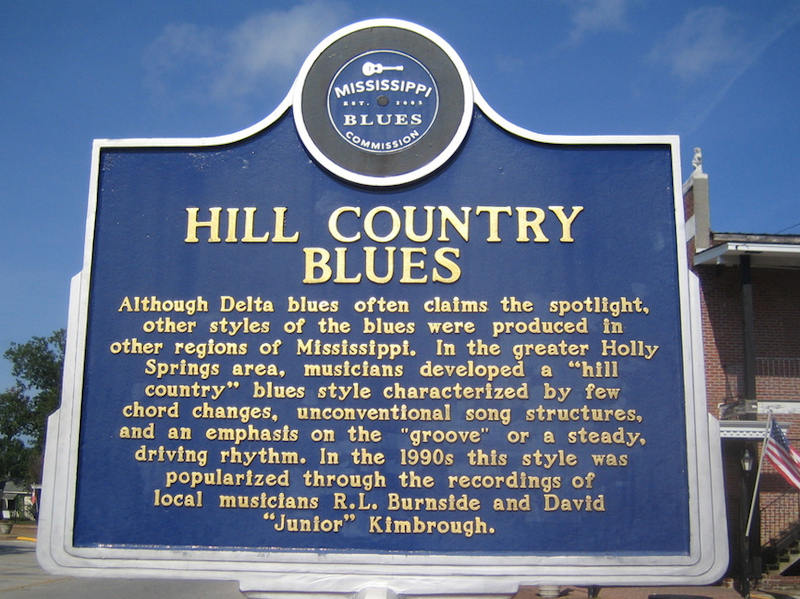

Mississippi Blues Trail Marker

Full text:

Although Delta blues often claims the spotlight, other styles of the blues were produced in other regions of Mississippi. In the greater Holly Springs area, musicians developed a “hill country” blues style characterized by few chord changes, unconventional song structures, and an emphasis on the “groove” or a steady, driving rhythm. In the 1990s this style was popularized through the recordings of local musicians R.L. Burnside and David “Junior” Kimbrough.

R.L. Burnside and Junior Kimbrough became unlikely heroes of the music world in the 1990s when their “hill country” style caught on in both blues and alternative rock music circles. Although Burnside (1926-2005) and Kimbrough (1930-1998) had both begun recording in the 1960s, they had mostly performed at local juke joints or house parties. Most of their early recordings had been made by field researchers and musicologists such as George Mitchell, David Evans of the University of Memphis, and Sylvester Oliver of Rust College. They developed a new, younger following after they appeared in the 1991 documentary Deep Blues and recorded for the Oxford-based Fat Possum label, and college students and foreign tourists mixed with locals at Kimbrough’s legendary juke joint in Chulahoma. Both artists toured widely and inspired musicians from Kansas to Norway to emulate their hill country sounds. Their songs were recorded by artists including the Black Keys and the North Mississippi Allstars, and remixes of Burnside tracks appeared in films, commercials, and the HBO series The Sopranos. The music of actor Samuel L. Jackson’s blues-singing character in the 2006 movie Black Snake Moan was largely inspired by Burnside.

Burnside, born in Lafayette County, was influenced by blues stars John Lee Hooker and Muddy Waters but also learned directly from local guitarists Mississippi Fred McDowell and Ranie Burnette. For most of his life Burnside worked as a farmer and fisherman. He only began to perform at festivals and in Europe in the 1970s. Burnside’s music took a more modern turn when sons Joseph, Daniel, and Duwayne Burnside and son-in-law Calvin Jackson played with him in his Sound Machine band. By the early ’90s Burnside was performing around the world in a trio with grandson Cedric Burnside and “adopted son” Kenny Brown. Following Burnside’s death his family, including grandson Kent Burnside, continued to perform his music, as did his protege Robert Belfour, a Holly Springs native who also recorded for the Fat Possum label.

Just as Burnside’s music reflected his jovial personality, the more introspective Junior Kimbrough produced singular music with a darker approach. Born into a musical family in Hudsonville, Kimbrough formed his first band in the late 1950s and recorded a single for the Philwood label in Memphis in 1968. In the 1980s his band, the Soul Blues Boys, featured longtime bassist Little Joe Ayers. In later years he was backed by his son Kinney on drums and R.L. Burnside’s son Garry on bass. Kimbrough’s multi-instrumentalist son David Malone devoted himself to carrying on his father’s legacy as well as developing his own style on recordings for Fat Possum and other labels.

Source: Wikipedia