Themed Photo Gallery and Information: Greenwood, Mississippi

History

Greenwood is a city in and the county seat of Leflore County, Mississippi, located at the eastern edge of the Mississippi Delta, approximately 96 miles north of the state capital, Jackson, Mississippi, and 130 miles south of the riverport of Memphis, Tennessee. It was a center of cotton planter culture in the 19th century.

The population was 16,087 at the 2010 census. It is the principal city of the Greenwood Micropolitan Statistical Area. Greenwood developed at the confluence of the Tallahatchie and the Yalobusha rivers, which form the Yazoo River. Throughout the 1960s, Greenwood was the site of major protests and conflicts as African Americans worked to achieve racial integration, voter registration and access during the civil rights movement.

The flood plain of the Mississippi River has long been an area rich in vegetation and wildlife, fed by the Mississippi and its numerous tributaries. Long before Europeans migrated to America, the Choctaw and Chickasaw Indian nations settled in the Delta’s bottomlands and throughout what is now central Mississippi. They were descended from indigenous peoples who had lived in the area for thousands of years. The Mississippian culture had built earthwork mounds in this area and throughout the Mississippi Valley, beginning about 950 CE. Their culture thrived for hundreds of years.

In the nineteenth century, the Five Civilized Tribes in the Southeast suffered increasing encroachment on their territory by European-American settlers from the United States. Under pressure from the United States government, in 1830 the Choctaw principal chief Greenwood LeFlore and other Choctaw leaders signed the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek, ceding most of their remaining land to the United States in exchange for land in Indian Territory, what is now southeastern Oklahoma. The government opened the land for sale and settlement by European Americans. LeFlore came to regret his decision on land cession, saying in 1843 that he was “sorry to say that the benefits realized from [the treaty] by my people were by no means equal to what I had a right to expect, nor to what they were justly entitled.”

The first Euro-American settlement on the banks of the Yazoo River was a trading post founded in 1834 by Colonel Dr. John J. Dilliard and known as Dilliard’s Landing. The settlement had competition from Greenwood Leflore’s rival landing called Point Leflore, located three miles up the Yazoo River. The rivalry ended when Captain James Dilliard donated parcels in exchange for a commitment from the townsmen to maintain an all-weather turnpike to the hill section to the east, along with a stagecoach road to the more established settlements to the northwest.

The settlement was incorporated as “Greenwood” in 1844, named after Chief Greenwood LeFlore. The success of the city, founded during a strong international demand for cotton, was based on its strategic location in the heart of the Delta: on the easternmost point of the alluvial plain, and astride the Tallahatchie and Yazoo rivers. The city served as a shipping point for cotton to major markets in New Orleans, Vicksburg, Mississippi, Memphis, Tennessee, and St. Louis, Missouri.

Thousands of slaves were transported as laborers to Mississippi from the Upper South through the domestic slave trade, in a forced migration that moved more than one million slaves in total to the Deep South to satisfy the demand for labor. Cotton cultivation was developed in these new territories of the Deep South. Greenwood continued to prosper, based on slave labor on the cotton plantations and in shipping, until the latter part of the American Civil War.

With the abolition of slavery after the end of the Civil War in 1865, the labor market was changed to one of free labor. Away from the riverfronts, the state was 90 per cent undeveloped frontier. Many freedmen withdrew from working for others. In the latter part of the nineteenth century, many blacks managed to clear and buy their own farms in the bottomlands behind the rivers. With the disruption caused by war and with changes to labor, cotton production initially declined, harming Greenwood’s previously thriving economy.

The construction of railroads through the area in the 1880s revitalized the city; two rail lines ran to downtown Greenwood close to the Yazoo River, and shortened transportation to markets. Greenwood again emerged as a prime shipping point for cotton. Downtown’s Front Street, bordering the Yazoo, was dominated by cotton factors and related businesses, earning that section the name ‘Cotton Row’. The city continued to prosper well into the 1940s. Cotton production suffered in Mississippi during the infestation of the boll weevil in the early 20th century; however, for many years the bridge over the Yazoo displayed the sign “World’s Largest Inland Long Staple Cotton Market”.

Cotton cultivation and processing became largely mechanized in the first half of the 20th century, displacing thousands of sharecroppers and tenant farmers. Since the late 20th century, some Mississippi farmers have begun to replace cotton with corn and soybeans as commodity crops; with the textile manufacturing industry having shifted overseas, farmers can gain stronger prices for the newer crops, used mostly as animal feed.

Greenwood’s Grand Boulevard was once named one of America’s 10 most beautiful streets by the U.S. Chambers of Commerce and the Garden Clubs of America. Sally Humphreys Gwin, a charter member of the Greenwood Garden Club, planted the 1,000 oak trees that line Grand Boulevard. In 1950, Gwin received a citation from the National Congress of the Daughters of the American Revolution in recognition of her work in the conservation of trees.

Civil Rights Era

In 1955, following the US Supreme Court’s ruling in Brown v. Board of Education that segregated public education was unconstitutional, Robert B. Patterson in Greenwood founded the White Citizens’ Council to fight against racial integration. Chapters were established across the state.

From 1962 to 1965, Greenwood was a center of protests and voter registration struggles during the Civil Rights Movement. The SNCC, COFO, and the MFDP were all active in the city. During this period, hundreds of African Americans were arrested in nonviolent protests; civil rights activists were subjected to repeated violence by police and whites. In addition, whites used economic retaliation against African Americans who attempted to register to vote: they fired them from jobs, evicted them from rental housing, and cut off federal commodity subsidies in poor communities.

The city police set their police dogs on protesters, with white counter-protesters yelling “Sic ’em” from the sidewalk.

The Catholic peace organization Pax Christi, which had a chapter in the city, organized an economic boycott of businesses that discriminated against blacks, thereby supporting the civil rights movement. Pax Christi’s ultimately successful efforts were encouraged by native Mississippian Joseph Bernard Brunini, the Bishop of Jackson.

Major gains were achieved by the movement with Congressional passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Voting Rights Act of 1965. However, much remained to be accomplished in terms of enacting these laws. White resistance to change continued. In June 1966, James Meredith, the first African American to attend the University of Mississippi, announced that to protest racism, he was going to walk from Memphis to Jackson, a distance of more than 200 miles, in a March Against Fear. He invited only men to walk with him, in a journey he wanted to be independent of the movement organizations. After Meredith was shot and hospitalized for injuries two days into his walk, a number of high-profile civil rights leaders of major organizations, including Stokely Carmichael of SNCC, Martin Luther King of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), Floyd McKissick and Roger Wilkins of the NAACP, vowed to continue the march. They encouraged others to join them.

Their goals differed, and organizing the logistics of food and shelter for larger groups were more difficult. The state committed to protect the marchers if they obeyed the law. Some groups expanded their goals in the march to achieve community organizing and voter registration in the Delta communities they encountered. National leaders tended to come and go, checking in on the march in the midst of other responsibilities; some marchers also walked for short periods, while others stayed through most of the journey. With high-spirited gatherings and song, they recruited marchers from local residents, for at least part of the journey. Many local whites jeered and threatened the marchers, driving near them and waving Confederate flags.

When the group reached Greenwood on June 17, Carmichael was arrested but released after a few hours. Later, in Greenwood’s Broad Street Park, Carmichael gave his Black Power speech, which became well known, stating:

This is the twenty-seventh time I have been arrested—and I ain’t going to jail no more! The only way we gonna stop them white men from whuppin’ us is to take over. We been sayin’ “freedom” for six years and we ain’t got nothin’. What we gonna start saying now is Black Power!

The speech marked a turning point in the civil rights movement; many younger members took up Carmichael’s slogan, and used it to support the use of violence to defend their freedom. This seemed to catalyze the fragmentation of the civil rights movement in the mid 1960s, but the process was already under way. On this occasion, the marchers persisted, growing in number as they neared the capital, and totaled more than 15,000 when they entered Jackson.

Source: Wikipedia

Mississippi Blues Trail Markers

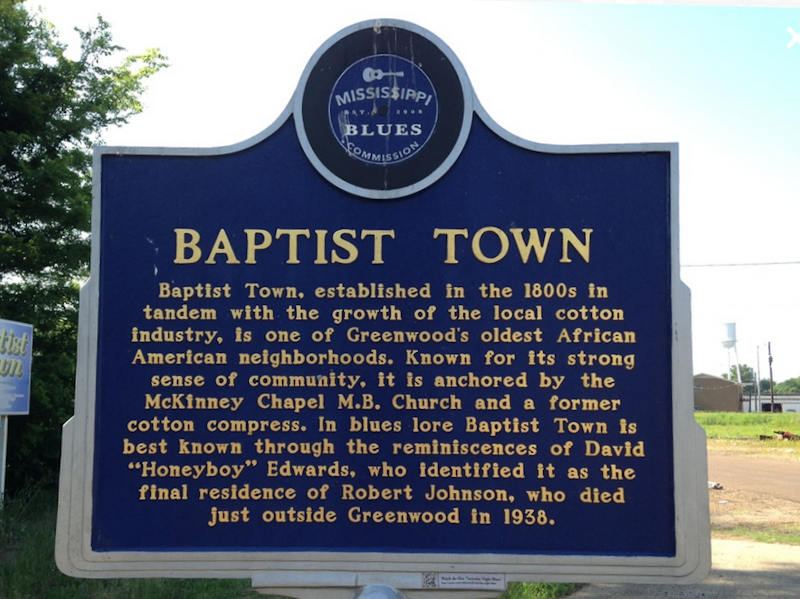

Full text:

Baptist Town, established in the 1800s in tandem with the growth of the local cotton industry, is one of Greenwood’s oldest African American neighborhoods. Known for its strong sense of community, it is anchored by the McKinney Chapel M.B. Church and a former cotton compress. In blues lore Baptist Town is best known through the reminiscences of David “Honeyboy” Edwards, who identified it as the final residence of Robert Johnson, who died just outside Greenwood in 1938.

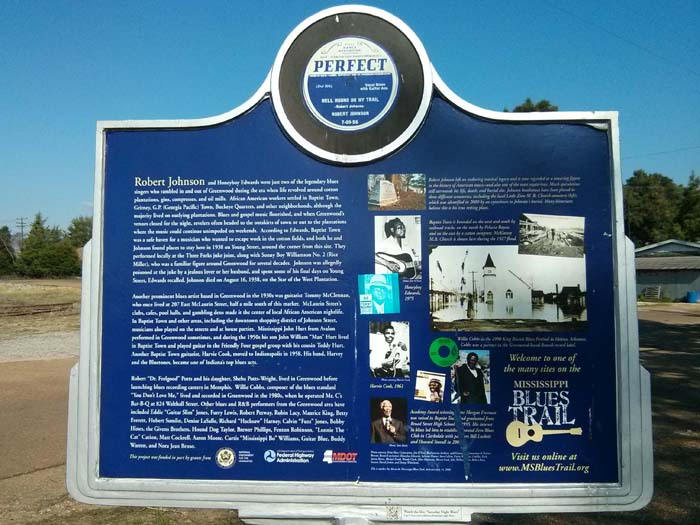

Robert Johnson and Honeyboy Edwards were just two of the legendary blues singers who rambled in and out of Greenwood during the era when life revolved around cotton plantations, gins, compresses, and oil mills. African American workers settled in Baptist Town, Gritney, G.P. (Georgia Pacific) Town, Buckeye Quarters, and other neighborhoods, although the majority lived on outlying plantations. Blues and gospel music flourished, and when Greenwood’s venues closed for the night, revelers often headed to the outskirts of town or out to the plantations where the music could continue unimpeded on weekends. According to Edwards, Baptist Town was a safe haven for a musician who wanted to escape work in the cotton fields, and both he and Johnson found places to stay here in 1938 on Young Street, around the corner from this site. They performed locally at the Three Forks juke joint, along with Sonny Boy Williamson No. 2 (Rice Miller), who was a familiar figure around Greenwood for several decades. Johnson was allegedly poisoned at the juke by a jealous lover or her husband, and spent some of his final days on Young Street, Edwards recalled. Johnson died on August 16, 1938, on the Star of the West Plantation.

Another prominent blues artist based in Greenwood in the 1930s was guitarist Tommy McClennan, who once lived at 207 East McLaurin Street, half a mile south of this marker. McLaurin Street’s clubs, cafes, pool halls, and gambling dens made it the center of local African American nightlife. In Baptist Town and other areas, including the downtown shopping district of Johnson Street, musicians also played on the streets and at house parties. Mississippi John Hurt from Avalon performed in Greenwood sometimes, and during the 1950s his son John William “Man” Hurt lived in Baptist Town and played guitar in the Friendly Four gospel group with his cousin Teddy Hurt. Another Baptist Town guitarist, Harvie Cook, moved to Indianapolis in 1958. His band, Harvey and the Bluetones, became one of Indiana’s top blues acts.

Robert “Dr. Feelgood” Potts and his daughter, Sheba Potts-Wright, lived in Greenwood before launching blues recording careers in Memphis. Willie Cobbs, composer of the blues standard “You Don’t Love Me,” lived and recorded in Greenwood in the 1980s, when he operated Mr. C’s Bar-B-Q at 824 Walthall Street. Other blues and R&B performers from the Greenwood area have included Eddie “Guitar Slim” Jones, Furry Lewis, Robert Petway, Rubin Lacy, Maurice King, Betty Everett, Hubert Sumlin, Denise LaSalle, Richard “Hacksaw” Harney, Calvin “Fuzz” Jones, Bobby Hines, the Givens Brothers, Hound Dog Taylor, Brewer Phillips, Fenton Robinson, “Lonnie The Cat” Cation, Matt Cockrell, Aaron Moore, Curtis “Mississippi Bo” Williams, Guitar Blue, Buddy Warren, and Nora Jean Bruso.

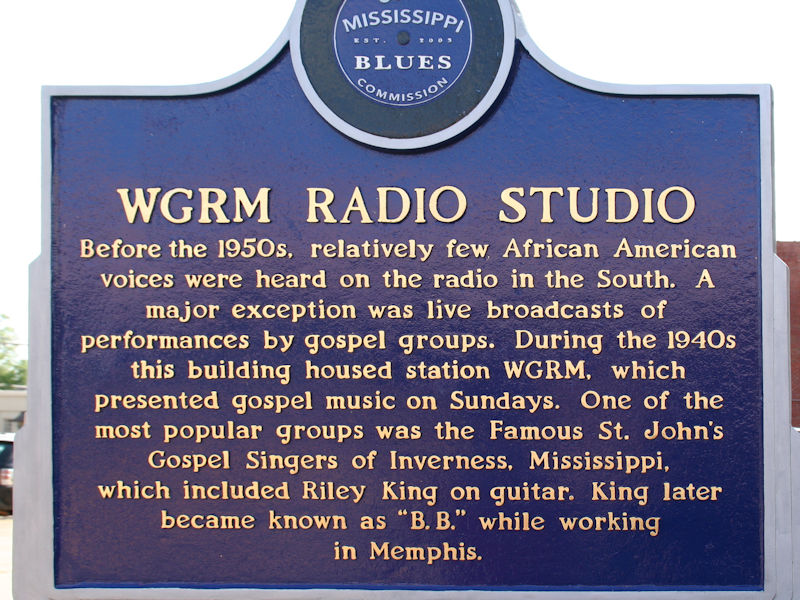

Full text:

Before the 1950s, relatively few African American voices were heard on the radio in the South. A major exception was live broadcasts of performances by gospel groups. During the 1940s this building housed station WGRM, which featured gospel music on Sundays. One of the most popular groups was the Famous St. John’s Gospel Singers of Inverness, Mississippi, which included Riley King on guitar. King later became known as “B.B.” while working in Memphis.

Radio broadcasting took off in the United States in the 1920s, but for the next several decades the voices of African Americans were largely excluded. Notable exceptions were the character “Rochester,” played by Eddie Anderson on the Jack Benny Show, which ran from 1932 to 1955, and harmonica player DeFord Bailey, one of the first stars of the country music program Grand Ole Opry, which began a radio broadcast in 1927 over Nashville’s WSM.

Another exception was live broadcasts of gospel music, including a CBS network show that featured the influential Golden Gate Quartet that debuted in 1940. The group’s programs had a major influence on young Riley King, who much later adopted the nickname “B.B.” In the mid-1940s, King (b. 1925) was singing lead and playing guitar with an Inverness-based gospel quartet, the Famous St. John’s Gospel Singers.

The group broadened their popularity through live Sunday afternoon broadcasts over radio station WGRM, which emanated from this building. King eventually became frustrated with the other quartet members’ reluctance to pursue a professional career and decided instead to focus on blues. In 1948 he moved to Memphis, where he found work as a disc jockey on WDIA, the first station in the United States to feature all African-American on-air personalities and broadcast content.

WGRM first went on the air in Grenada in 1938 and moved here in 1939. At the time it was one of only nine radio stations in the state. Most programming on WGRM was provided by the Blue Network, owned initially by NBC and after 1943 by ABC, with several locally produced music programs, including the one featuring King’s gospel group running on the weekends.

By the mid-1950s WGRM had moved to North Greenwood, and this building was occupied by WABG radio. In rural areas radio stations often doubled as recording studios, and the Greenwood-based band of pianist Bobby Hines recorded in such a setting, according to his guitarist Brewer Phillips. Recorded at WGRM were Matt Cockrell and L. C. “Lonnie the Cat” Cation, accompanied by the Hines band with talent scout Ike Turner also on piano. Both saw release in April 1954 on Los Angeles-based RPM, B.B. King’s label at the time. Cation’s single “I Ain’t Drunk (I’m Just Drinking)” later became a blues standard via covers by Jimmy Liggins and Albert Collins.

Full text:

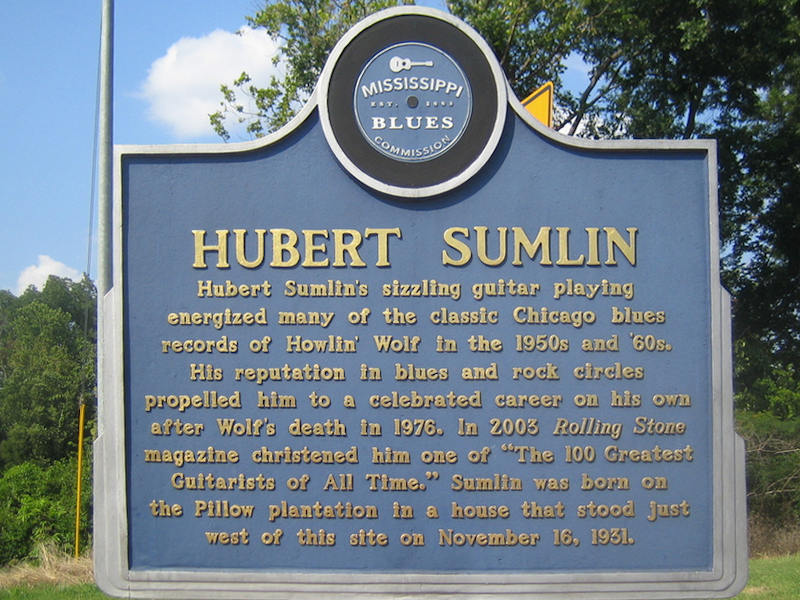

Hubert Sumlin’s sizzling guitar playing energized many of the classic Chicago blues records of Howlin’ Wolf in the 1950s and ‘60s. His reputation in blues and rock circles propelled him to a celebrated career on his own after Wolf’s death in 1976. In 2003 Rolling Stone magazine christened him one of “The 100 Greatest Guitarists of All Time.” Sumlin was born on the Pillow plantation in a house that stood just west of this site on November 16, 1931.

Hubert Sumlin grew up in Mississippi and Arkansas hearing his churchgoing mother admonish him for playing “the devil’s music”—the blues. But he found out, after sneaking in some blues licks on his guitar in church, that the sounds of the blues could win over even his mother. Sumlin’s innovative musicianship and endearing nature won the hearts of many musicians and admirers in the decades to follow. His boyhood partner, harmonica legend James Cotton, remained a lifelong friend. From 1954 to 1976 Howlin’ Wolf was as much a father figure to Sumlin as he was his musical employer. In later years Sumlin was adopted by a wide range of musicians, club owners, promoters, and producers who crafted a niche for him as a special guest or featured soloist.

Sumlin started playing guitar in church, but was performing blues with James Cotton by the time the two were in their teens, after the Sumlin family had moved from Greenwood to Hughes, Arkansas. Hubert was awestruck at seeing Howlin’ Wolf rock the house at a local juke joint, and when Wolf later offered him a spot in his band in Chicago, Sumlin bade farewell to Cotton and to his family in Arkansas. Sumlin’s years with Wolf were highlighted by groundbreaking recordings such as “Killing Floor,” “300 Pounds of Joy,” “Smokestack Lightning,” and “Shake For Me” for the Chess label in Chicago. Wolf, a stern disciplinarian, fired his protégé on numerous occasions, only to rehire him every time. At one time Hubert even joined the band of Wolf’s main rival, Muddy Waters. He also played guitar on records by Muddy, Chuck Berry, Jimmy Reed, Willie Dixon, Sonny Boy Williamson (Rice Miller), Eddie Taylor, Sunnyland Slim, Carey Bell, Eddie Shaw, James Cotton, and many others.

When Sumlin and Wolf toured Europe on the 1964 American Folk Blues Festival, Hubert made his first recordings under his own name in Germany and England. His only 45 rpm single came from an acoustic blues session which also marked the first release on the historic Blue Horizon label in England. In later years he recorded albums for labels in France, Germany, Argentina, and the United States. Jimi Hendrix and Stevie Ray Vaughan are two of the many guitarists who have named Sumlin as a favorite. He shared stages with Eric Clapton, the Rolling Stones, Santana, Aerosmith, and many others. On the award-winning album About Them Shoes Hubert was joined by Clapton, Keith Richards, Levon Helm, and James Cotton. On May 7, 2008, the day after the unveiling of this marker, Sumlin was inducted into the Blues Foundation’s Blues Hall of Fame.

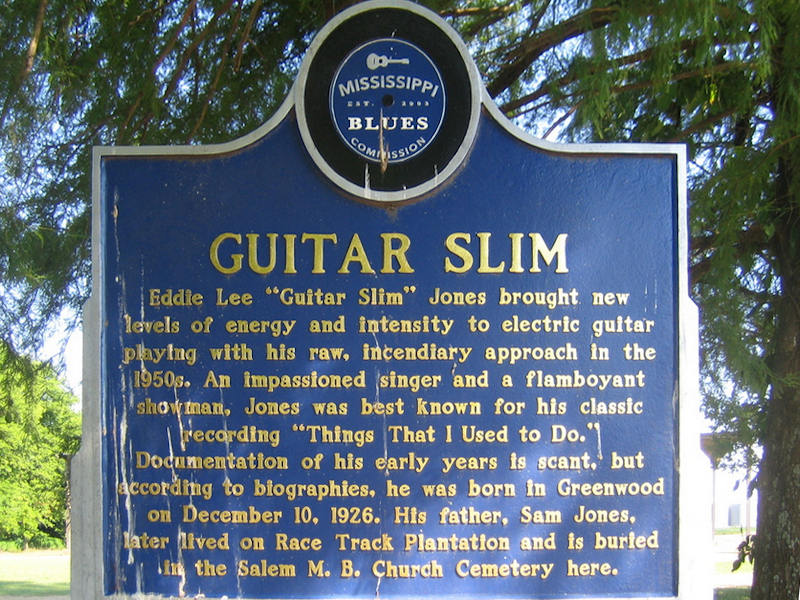

Full text:

Eddie Lee “Guitar Slim” Jones brought new levels of energy and intensity to electric guitar playing with his raw, incendiary approach in the 1950s. An impassioned singer and a flamboyant showman, Jones was best known for his classic recording “Things That I Used To Do.” Documentation of his early years is scant, but according to biographies, he was born in Greenwood on December 10, 1926. His father, Sam Jones, later lived on Race Track Plantation and is buried in the Salem M. B. Church Cemetery here.

Guitar Slim was the hottest name in the blues world in 1954 when he burst out of New Orleans with the smash hit “The Things That I Used to Do,” but in the Mississippi Delta where he was born and raised, people still knew him as Eddie Jones, a choir boy turned jitterbug dancer. Jones, whose mother died when he was a child, spent only his first few years in the Greenwood area and grew up in Hollandale with his maternal grandmother Mollie Edwards. Jones first attracted attention there for his sensational dancing, earning nicknames like “Limber Leg Eddie” or “Rubber Legs.” After Jones returned home from World War II service, Delta bluesmen Willie D. Warren and Little Bill Wallace recruited him to join them to perform in Arkansas and Louisiana. Jones, also known for his ability to imitate Louis Jordan and other singers at the time, ended up on his own in New Orleans where he first played the streets and house parties but soon emerged with a freshly developed command of the guitar and a new name, “Guitar Slim.” Guitarist Robert Nighthawk had been an early inspiration in Hollandale, but it was Texas maestro Gatemouth Brown whose style impacted Slim the most.

His recording of “The Things That I Used to Do” was the biggest rhythm & blues hit of 1954 and one of the three top R&B records of the entire ‘50s decade, according to Billboard magazine. Guitar Slim never had another hit of such proportions, but he thrilled audiences from coast to coast with his exciting live performances. Decked out in brightly colored suits and shoes with hair sometimes dyed to match or contrast, he combined dancing acrobatics with his guitar work, often strolled out the door with a 50- to 350-foot cord (estimates vary) to play guitar, and sang with the fervor of a fire-and-brimstone preacher. His offstage party life was just as wild. A troubled and serious side came through, however, in his heartfelt original lyrics, enough so that Atco Records advertised in 1958: “Guitar Slim is a philosopher. His songs are exclusively concerned with the earthy truisms of life.” The fast life finally wore Guitar Slim down and he succumbed to pneumonia in New York City on February 7, 1959. He was reportedly 32, although some documents suggest he may have been about two years older.

Guitar Slim has been cited as a major influence by many blues and rock guitarists, from Buddy Guy, Chick Willis, and Lonnie Brooks to Frank Zappa, Stevie Ray Vaughan, and Billy Gibbons, and he has been called the predecessor of Jimi Hendrix for the free-spirited, ferocious way he attacked his guitar. He was inducted into the Blues Hall of Fame in 2007.

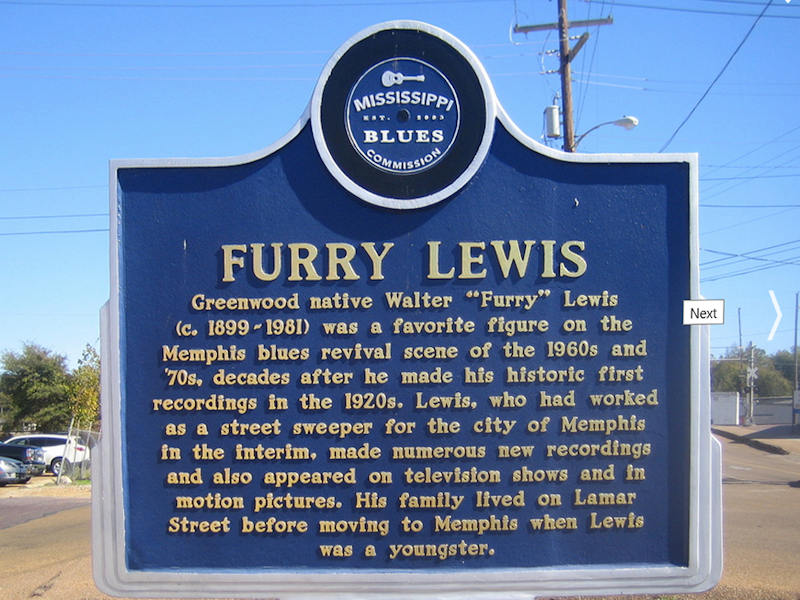

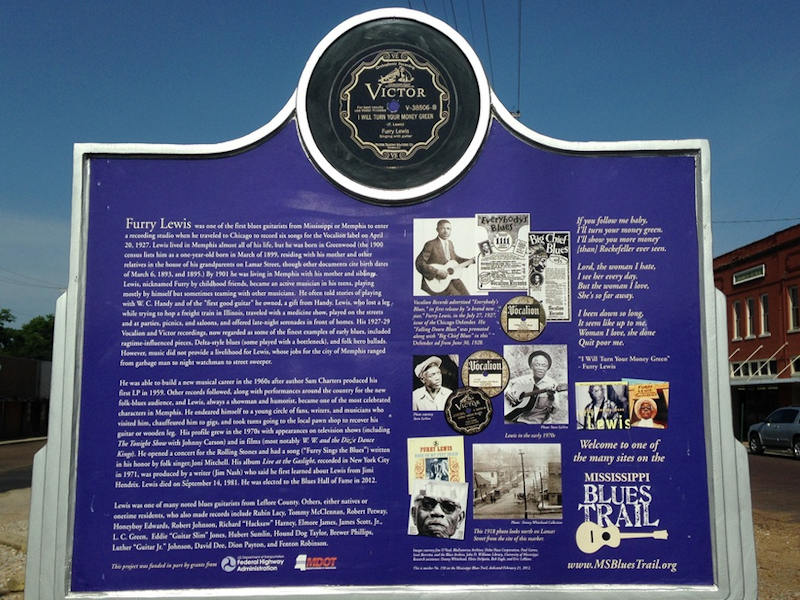

Full text:

Greenwood native Walter “Furry” Lewis (c. 1899-1981) was a favorite figure on the Memphis blues revival scene of the 1960s and ’70s, decades after he made his historic first recordings in the 1920s. Lewis, who had worked as a street sweeper for the city of Memphis in the interim, made numerous new recordings and also appeared on television shows and in motion pictures. His family lived on Lamar Street before moving to Memphis when Lewis was a youngster.

Furry Lewis was one of the first blues guitarists from Mississippi or Memphis to enter a recording studio when he traveled to Chicago to record six songs for the Vocalion label on April 20, 1927. Lewis lived in Memphis almost all of his life, but he was born in Greenwood (the 1900 census lists him as a one-year-old born in March of 1899, residing with his mother and other relatives in the house of his grandparents on Lamar Street, though other documents cite birth dates of March 6, 1893, and 1895.) By 1901 he was living in Memphis with his mother and siblings. Lewis, nicknamed Furry by childhood friends, became an active musician in his teens, playing mostly by himself but sometimes teaming with other musicians. He often told stories of playing with W. C. Handy and of the “first good guitar” he owned, a gift from Handy. Lewis, who lost a leg while trying to hop a freight train in Illinois, traveled with a medicine show, played on the streets and at parties, picnics, and saloons, and offered late-night serenades in front of homes. His 1927-29 Vocalion and Victor recordings, now regarded as some of the finest examples of early blues, included ragtime-influenced pieces, Delta-style blues (some played with a bottleneck), and folk hero ballads. However, music did not provide a livelihood for Lewis, whose jobs for the city of Memphis ranged from garbage man to night watchman to street sweeper.

He was able to build a new musical career in the 1960s after author Sam Charters produced his first LP in 1959. Other records followed, along with performances around the country for the new folk-blues audience, and Lewis, always a showman and humorist, became one of the most celebrated characters in Memphis. He endeared himself to a young circle of fans, writers, and musicians who visited him, chauffeured him to gigs, and took turns going to the local pawn shop to recover his guitar or wooden leg. His profile grew in the 1970s with appearances on television shows (including The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson) and in films (most notably W. W. and the Dixie Dance Kings). He opened a concert for the Rolling Stones and had a song (“Furry Sings the Blues”) written in his honor by folk singer Joni Mitchell. His album Live at the Gaslight, recorded in New York City in 1971, was produced by a writer (Jim Nash) who said he first learned about Lewis from Jimi Hendrix. Lewis died on September 14, 1981. He was elected to the Blues Hall of Fame in 2012.

Lewis was one of many noted blues guitarists from Leflore County. Others, either natives or onetime residents, who also made records include Rubin Lacy, Tommy McClennan, Robert Petway, Honeyboy Edwards, Robert Johnson, Richard “Hacksaw” Harney, Elmore James, James Scott, Jr., L. C. Green, Eddie “Guitar Slim” Jones, Hubert Sumlin, Hound Dog Taylor, Brewer Phillips, Luther “Guitar Jr.” Johnson, David Dee, Dion Payton, and Fenton Robinson.

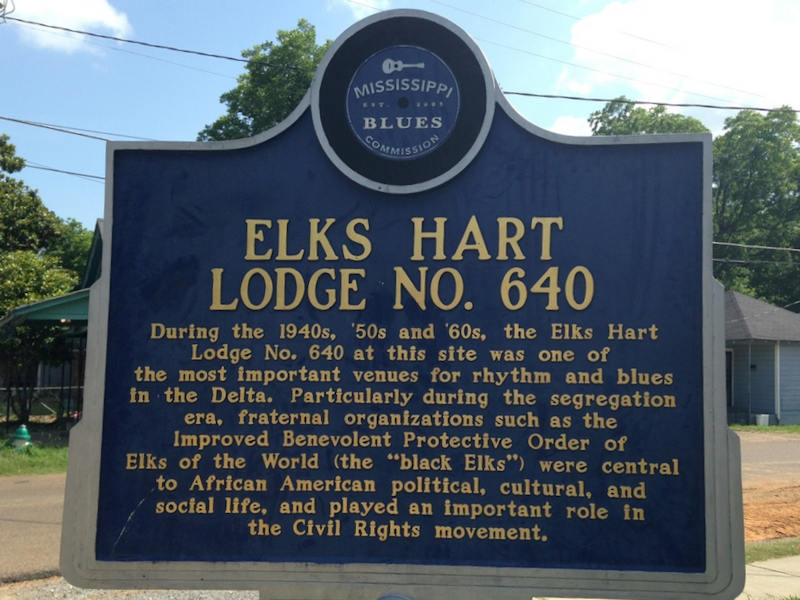

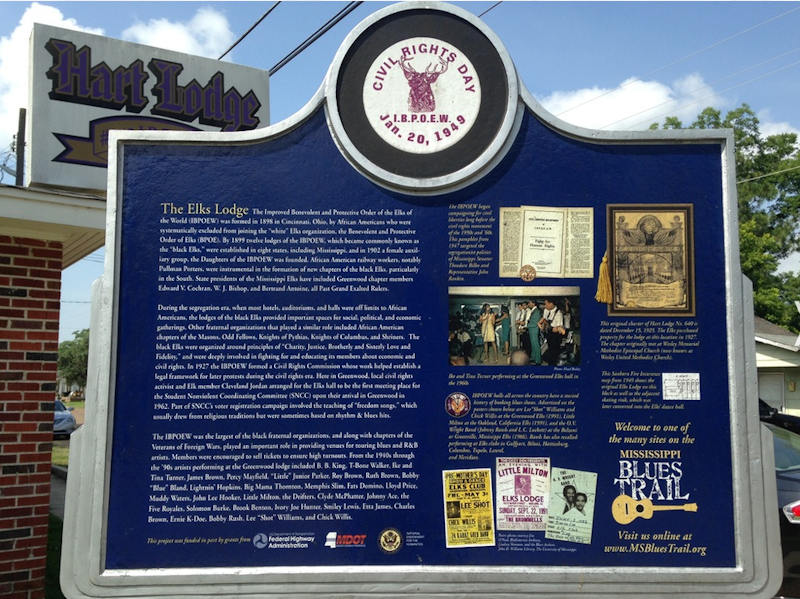

Full text:

During the 1940s, ’50s and ’60s, the Elks Hart Lodge No. 640 at this site was one of the most important venues for rhythm and blues in the Delta. Particularly during the segregation era, fraternal organizations such as the Improved Benevolent Protective Order of Elks of the World (the “black Elks”) were central to African American political, cultural, and social life, and played an important role in the Civil Rights movement.

The Improved Benevolent and Protective Order of the Elks of the World (IBPOEW) was formed in 1898 in Cincinnati, Ohio, by African Americans who were systematically excluded from joining the “white” Elks organization, the Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks (BPOE). By 1899 twelve lodges of the IBPOEW, which became commonly known as the “black Elks,” were established in eight states, including Mississippi, and in 1902 a female auxiliary group, the Daughters of the IBPOEW was founded. African American railway workers, notably Pullman Porters, were instrumental in the formation of new chapters of the black Elks, particularly in the South. State presidents of the Mississippi Elks have included Greenwood chapter members Edward V. Cochran, W. J. Bishop, and Bertrand Antoine, all Past Grand Exalted Rulers.

During the segregation era, when most hotels, auditoriums, and halls were off limits to African Americans, the lodges of the black Elks provided important spaces for social, political, and economic gatherings. Other fraternal organizations that played a similar role included African American chapters of the Masons, Odd Fellows, Knights of Pythias, Knights of Columbus, and Shriners. The black Elks were organized around principles of “Charity, Justice, Brotherly and Sisterly Love and Fidelity,” and were deeply involved in fighting for and educating its members about economic and civil rights. In 1927 the IBPOEW formed a Civil Rights Commission whose work helped establish a legal framework for later protests during the civil rights era. Here in Greenwood, local civil rights activist and Elk member Cleveland Jordan arranged for the Elks hall to be the first meeting place for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) upon their arrival in Greenwood in 1962. Part of SNCC’s voter registration campaign involved the teaching of “freedom songs,” which usually drew from religious traditions but were sometimes based on rhythm & blues hits.

The IBPOEW was the largest of the black fraternal organizations, and along with chapters of the Veterans of Foreign Wars, played an important role in providing venues for touring blues and R&B artists. Members were encouraged to sell tickets to ensure high turnouts. From the 1940s through the ’90s artists performing at the Greenwood lodge included B. B. King, T-Bone Walker, Ike and Tina Turner, James Brown, Percy Mayfield, “Little” Junior Parker, Roy Brown, Ruth Brown, Bobby “Blue” Bland, Lightnin’ Hopkins, Big Mama Thornton, Memphis Slim, Fats Domino, Lloyd Price, Muddy Waters, John Lee Hooker, Little Milton, the Drifters, Clyde McPhatter, Johnny Ace, the Five Royales, Solomon Burke, Brook Benton, Ivory Joe Hunter, Smiley Lewis, Etta James, Charles Brown, Ernie K-Doe, Bobby Rush, Lee “Shot” Williams, and Chick Willis.

Photo Gallery

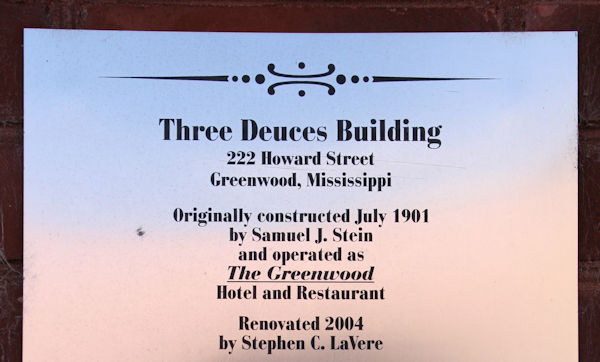

Three Deuces Building, 222 Howard Street, one time home of WRGM Radio and more recently the late Steve LaVere’s Greenwood Blues Heritage Museum, Blue Parrot Cafe and Veronica’s Bakery.

Plaque on the wall of 222 Howard street, renovated as part of Greenwood’s Historic Downtown district.

My first visit to Greenwood was during the “Railroadin’ Some” book signing tour in 2006 with author Max Haymes and his brother Rex. The photo shows Max and Steve in the museum. We had lunch with Steve and spent the afternoon discussing blues and of course a guided tour of Steve’s 30+ years of collecting Robert Johnson memorabilia (the very essence of the museum). The highlight of the museum is reputedly the only complete set of Robert Johnson’s 78 records, including alternate takes, locked in an antique wooden case (once part of a Greenwood drug store). The museum now has the “Railroadin’ Some” book on display and one of my t-shirts promoting the book in the racks (to the right in the photo) – as confirmed on my second visit with my wife Christine several years later when we met Steve’s son George Vasquez. Sadly Steve passed in 2015 and there is an obituary on the Big Road Blues website which you can read here.

Greenwood City Hall was built in the Beaux Arts architectural style. On the day of its grand opening in 1930, visitors were greeted by a sign of a Greek Letter Delta with the legend, “Greenwood, Gateway of the Delta”, and in the centre of the letter, a bale of cotton.

National Register of Historic Places marker of Greenwood’s Cotton Row District – a district comprised the “state’s most important concentration of buildings associated with marketing of cotton and with the state’s post-Civil War cotton boom”. The Yazoo River is in the background.

The Cotton Row Club used to be a favourite gathering place for cotton brokers and other businessmen during the cotton capital’s heyday.

Cotton Row District building.