Themed Photo Gallery and Information: Como, Mississippi

History

Como is a town in Panola County, Mississippi, which borders the Mississippi Delta and is in the northern part of the state, known as hill country. The population was 1,279 as of the 2010 census. It is in a relatively isolated rural area, which has struggled with the legacy of slavery, segregation and agricultural decline.

Mississippi Fred McDowell, Jessie Mae Hemphill, Napoleon Strickland, Othar Turner, and R.L. Boyce are noted Hill Country blues musicians who lived in or near Como.

Jimbo Mathus, musician, has lived in Como since 2007, where he also runs the Delta Recording Studio, which records artists from around the world.

Source: Wikipedia

Mississippi Blues Trail Markers

Full text:

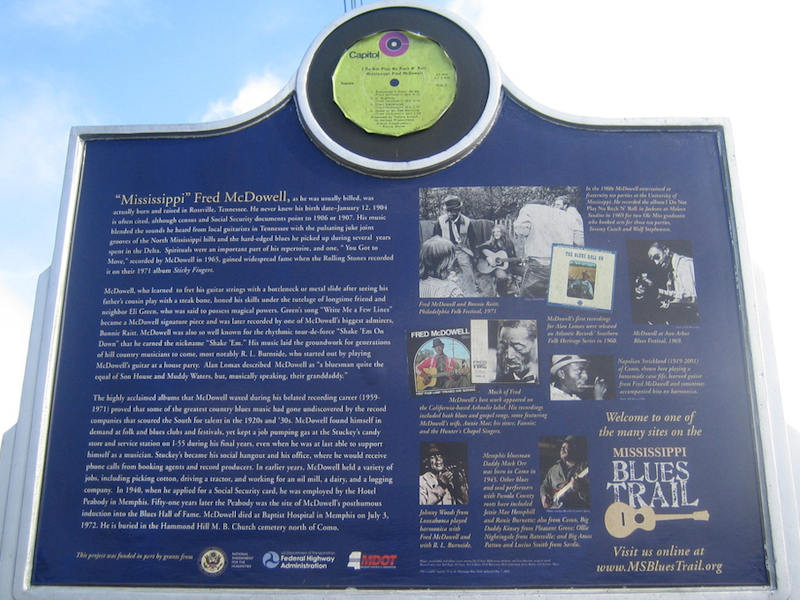

Fred McDowell, a seminal figure in Mississippi hill country blues, was one of the most vibrant performers of the 1960s blues revival. McDowell (c. 1906-1972) was a sharecropper and local entertainer in 1959 when he made his first recordings at his home on a farm north of Como for noted folklorist Alan Lomax. The depth and originality of McDowell’s music brought him such worldwide acclaim that he was able to record and tour prolifically during his final years.

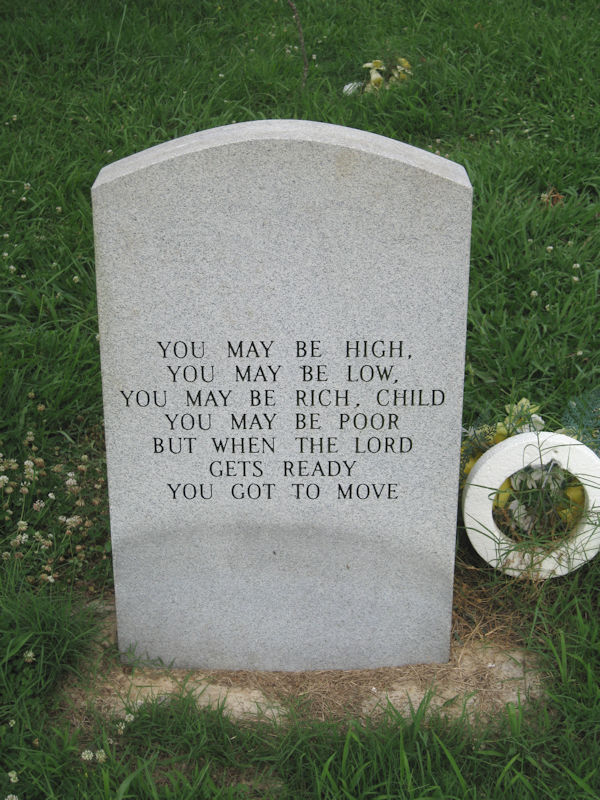

“Mississippi” Fred McDowell, as he was usually billed, was actually born and raised in Rossville, Tennessee. He never knew his birth date–January 12, 1904 is often cited, although census and Social Security documents point to 1906 or 1907. His music blended the sounds he heard from local guitarists in Tennessee with the pulsating juke joint grooves of the North Mississippi hills and the hard-edged blues he picked up during several years spent in the Delta. Spirituals were an important part of his repertoire, and one, “You Got to Move,” recorded by McDowell in 1965, gained widespread fame when the Rolling Stones recorded it on their 1971 album Sticky Fingers.

McDowell, who learned to fret his guitar strings with a bottleneck or metal slide after seeing his father’s cousin play with a steak bone, honed his skills under the tutelage of longtime friend and neighbor Eli Green, who was said to possess magical powers. Green’s song “Write Me a Few Lines” became a McDowell signature piece and was later recorded by one of McDowell’s biggest admirers, Bonnie Raitt. McDowell was also so well known for the rhythmic tour-de-force “Shake ’Em On Down” that he earned the nickname “Shake ’Em.” His music laid the groundwork for generations of hill country musicians to come, most notably R. L. Burnside, who started out by playing McDowell’s guitar at a house party. Alan Lomax described McDowell as “a bluesman quite the equal of Son House and Muddy Waters, but, musically speaking, their granddaddy.”

The highly acclaimed albums that McDowell waxed during his belated recording career (1959-1971) proved that some of the greatest country blues music had gone undiscovered by the record companies that scoured the South for talent in the 1920s and ‘30s. McDowell found himself in demand at folk and blues clubs and festivals, yet kept a job pumping gas at the Stuckey’s candy store and service station on I-55 during his final years, even when he was at last able to support himself as a musician. Stuckey’s became his social hangout and his office, where he would receive phone calls from booking agents and record producers. In earlier years, McDowell held a variety of jobs, including picking cotton, driving a tractor, and working for an oil mill, a dairy, and a logging company. In 1940, when he applied for a Social Security card, he was employed by the Hotel Peabody in Memphis. Fifty-one years later the Peabody was the site of McDowell’s posthumous induction into the Blues Hall of Fame. McDowell died at Baptist Hospital in Memphis on July 3, 1972. He is buried in the Hammond Hill M. B. Church cemetery north of Como.

Full text:

One of the few female performers of country blues, Jessie Mae Hemphill (c. 1923 – 2006) was a multi-instrumentalist who performed in local fife and drum bands before gaining international recognition in the 1980s as a vocalist and guitarist. Her grandfather, Sid Hemphill, was a leading musician in the area, and his daughters, including Jessie Mae’s mother Virgie Lee, all played drums and stringed instruments. She is buried here at the Senatobia Memorial Cemetery.

Jessie Mae Hemphill, who struck a unique chord with blues fans due to her colorful personality and attire and her choice of instruments, represented deep and rich traditions in the Senatobia area. Her great-grandfather, Dock Hemphill, was a fiddler who was born a slave, and her grandfather, Sid Hemphill (c. 1876-1963), played fiddle, guitar, banjo, drums, fife, mandolin, organ, and quills. Folklorists Alan Lomax of the Library of Congress and Lewis Jones of Fisk University documented Hemphill’s broad repertoire at a recording session in Sledge in 1942. Lomax, who recorded music around the world and returned to record Hemphill in 1959, later recalled that encountering Hemphill’s fife and drum music was the “main find of my whole career.”

Sid Hemphill’s daughters, Rosa Lee, Sidney, and Virgie Lee, were all musicians, and when Jessie Mae was a small girl her grandfather inspired her to take up guitar, harmonica, and drums. During the 1950s she sang briefly with bands in Memphis, but most of her early musical experiences were local. Folklorist George Mitchell, who included chapters on her and her aunt Rosa Lee Hill in his book Blow My Blues Away, recorded her in the late ’60s. Her first 45 rpm single, produced by Dr. David Evans, was released on the University of Memphis’ High Water label in 1980. Hemphill subsequently toured the U.S. and Europe, recorded several albums, and won several W. C. Handy Awards for traditional blues. She played drums behind fife player Otha Turner on Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood, and gained broader acclaim via her appearance in the 1992 documentary film Deep Blues. In 1993 Hemphill suffered a stroke that prevented her from playing guitar, but she continued to sing, and in 2004 she was featured singing and playing tambourine on the album Dare You to Do It Again, which featured many local musicians.

Other Senatobia area musicians who played in distinctive local folk traditions include many members of the extended family of Otha Turner, including his granddaughter and fife player Sharde Thomas; fife players Napolian Strickland and Ed Young; drummers Lonnie Young, Abe (“Cag” or “Kag”) Young and R. L. Boyce; diddley bow players Glen Faulkner and Compton Jones; guitarists Sandy Palmer and Ranie Burnette (who was a major influence on R. L. Burnside); harmonica player Johnny Woods; banjoist Lucius Smith; and vocalist James Shorter, who recorded with Jessie Mae Hemphill. Artists who left the area and performed in more modern styles include guitarist Willie Johnson and bassists Calvin “Fuzz” Jones and Aron Burton, all of whom moved to Chicago; Wordie Perkins, guitarist with the Memphis band the Fieldstones; and Kalamazoo, Michigan, soul/blues vocalist Lou Wilson.

Full text:

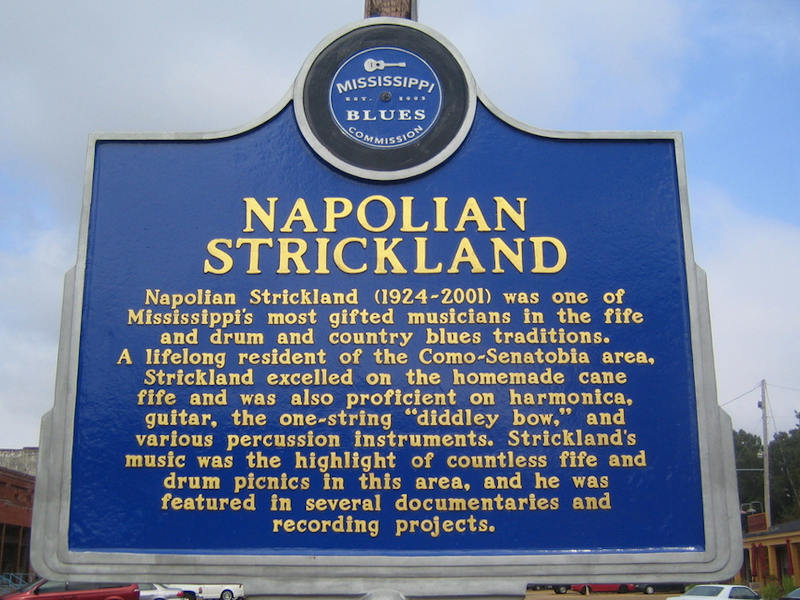

Napolian Strickland (1924-2001) was one of Mississippi’s most gifted musicians in the fife and drum and country blues traditions. A lifelong resident of the Como-Senatobia area, Strickland excelled on the homemade cane fife and was also proficient on harmonica, guitar, the one-string “diddley bow,” and various percussion instruments. Strickland’s music was the highlight of countless fife and drum picnics in this area, and he was featured in several documentaries and recording projects.

Napolian Strickland was Mississippi’s most in-demand fife player for several decades, regularly called upon to entertain at hill country picnics and sought out by folklorists eager to film and record his captivating performances. Strickland made his first recordings in 1967 for George Mitchell and later recorded for David Evans, Bill Ferris, Chris Strachwitz and Alan Lomax, all prominent folklorists or producers. In 1978 Lomax–who had earlier recorded local fife players Sid Hemphill (1942) and Ed Young (1959)–filmed Strickland for the documentary The Land Where the Blues Began and later devoted several pages to him in the book of the same name. Strickland’s recordings appeared on the Arhoolie, Testament, Blue Thumb, Southern Culture, and Library of Congress labels, among others. The first band Strickland joined was Otha Turner’s. Turner appeared as a drummer on several of Strickland’s records and later became the area’s most celebrated fife player and picnic host.

Strickland, who was born a few miles east of Como, recalled learning fife on his own, blowing the instrument while walking up and down country roads. He was reportedly inspired by a fife player who played with drummer John Tyler’s group in Sardis. Strickland also talked of learning to play music by following his grandfather’s instructions to sit on a grave in a cemetery at midnight. Strickland enlivened picnics both with his fife, leading a procession of drummers through the crowds, and with his uninhibited moves. The picnics included reunions, family gatherings, church socials, and celebrations sponsored by local farmers and businesses. Strickland did farm work for most of his life, often living with and working alongside his mother, Dora Tuggle, and occasionally traveling to play at festivals. Sometimes described as a savant, he went to the fourth grade in school, according to census records. Although different birth dates have been cited, including 1919 in Social Security files, his birth certificate was dated October 6, 1924. His first name was spelled several different ways in official records, as was that of his grandfather, Napoleon Wilford, but family sources rendered it as Napolian at his funeral. Strickland lived in a convalescent home in his final years and died at North Oak Regional Medical Center in Senatobia on July 21, 2001. Several events have been held in his honor in Como, including Napoleon Strickland Day, organized by Julius Harris and Beverly Findley.

Among the musicians who worked often with Strickland and Turner was R. L. Boyce (b. August 15, 1955). Boyce played drums on recording sessions with other artists, including Jessie Mae Hemphill, and recorded on his own singing and playing guitar. Other Como fife players have included John Bowden (1903-2000), who inspired Turner, and Willie Hurt. R&B singer Joe Henderson lived on the Hayes plantation, southwest of Sardis, as did guitarist Lester “Big Daddy” Kinsey and banjoist Lucius Smith. Henderson and Kinsey both moved to Gary, Indiana. Henderson (1937-1964), a Como native, recorded the Top Ten hit “Snap Your Fingers” in 1962.

Full text:

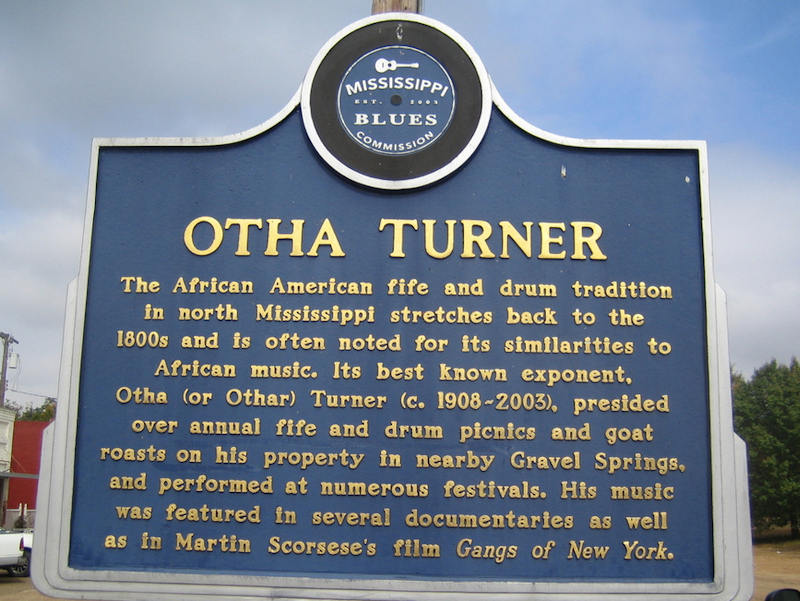

The African American fife and drum tradition in north Mississippi stretches back to the 1800s and is often noted for its similarities to African music. Its best known exponent, Otha (or Othar) Turner (c. 1908-2003), presided over annual fife and drum picnics and goat roasts on his property in nearby Gravel Springs, and performed at numerous festivals. His music was featured in several documentaries as well as in Martin Scorsese’s film Gangs of New York.

The fife and drum ensemble is most closely associated with military marches, but African American bands in North Missisippi have long used fifes and drums to provide entertainment at picnics and other social events. Many scholars believe that such groups formed in the wake of the Civil War, perhaps using discarded military instruments. Prior to the war slaves were largely forbidden from playing drums out of fear that they would use the instruments for secret communication, though African Americans did serve in military units as musicians, playing fifes, drums, and trumpets. North Mississippi fife and drum music is often described as sounding “African,” but it was not imported directly from Africa. Instead it appears that African American musicians infused the Euro-American military tradition with distinctly African polyrhythms, riff structures, and call-and-response patterns. Fife and drum bands have performed spirituals, minstrel songs, instrumental pieces such as “Shimmy She Wobble,” and versions of blues hits including the Mississippi Sheiks’ “Sitting On Top of the World” and Little Walter’s “My Babe.” While the black fife and drum tradition is identified with northern Mississippi, researchers have also documented the music in other areas, including southwestern Mississippi, western Tennessee, and west central Georgia.

In 1942 multi-instrumentalist Sid Hemphill and his band made the first recordings of Mississippi fife and drum music for Library of Congress folklorist Alan Lomax. His granddaughter, blues singer-guitarist Jessie Mae Hemphill, later played drums in local fife and drum bands. Lomax also recorded fife and drum music by brothers Ed and Lonnie Young in 1959. In the 1960s and ’70s folklorists George Mitchell, David Evans, and Bill Ferris recorded groups featuring Napolian Strickland (c. 1919-2001) on fife and Otha Turner on bass drum.

Turner, born in Rankin County around 1908—various sources suggest birth years ranging from 1903 to 1917—moved to northern Mississippi as a child together with his mother, Betty Turner. He learned to create his own fifes by using a heated metal rod to hollow out and bore a mouth hole and five finger holes into a piece of bamboo cane. Turner, who spent most of his life as a farmer, eventually became the patriarch of the regional fife and drum tradition. He recorded as leader of the Rising Star Fife and Drum Band for various American and European labels and appeared in several documentaries, including Gravel Springs Fife and Drum, Lomax’s Land Where the Blues Began, and Martin Scorsese’s Feel Like Going Home. Following his death in 2003 his granddaughter and protégé Sharde Thomas inherited leadership of his fife and drum band.

Source: http://msbluestrail.org/

Photo Gallery